Creators, Makers, & Doers: Keiran Brennan Hinton

Posted on 1/10/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

We are incredibly pleased to have welcomed Keiran Brennan Hinton as our first Artist-In-Residence at the James Castle House. Keiran attended a unique high school in Toronto Canada, Etobicoke School of the Arts, designed to focus on developing relevant creative content. During his final semester in college, he applied, on a whim, to graduate school at Yale University. And got in. Spending an afternoon with Keiran toward the end of his residency, we appreciated his thoughtful consideration of a lifetime of work by James Castle. His response: dive into the work and it will open up a world that becomes deeper and deeper, if you are able to give it your time and respect. We found exactly the same to be true about a conversation with Keiran. Be receptive, listen closely, and he will share deeply about the nature of a hard, fast mark on canvas, about space, air, time, and atmosphere as a thing you can almost touch, and about the primal qualities of liquid, buttery, and crunchy paint as it relates to our sensation of skin and touch. Ideally, Keiran is hopeful you will have your own emotional response to artwork; a response to the paint itself, to the quality of the brushstrokes, and to what is (or is not) depicted therein. But Keiran, thank you for opening up about the importance of trusting yourself and about looking closely at what is right in front of you. We needed that.

We’re very excited to have you as our first Artist in Residence. Thanks for coming to Idaho. I’ve seen your work online and notice you paint interiors and sometimes, wallpaper. How perfect then to come live and paint inside the James Castle House! Where did you start?

Within the first week, the staff took me out to the shed and it felt like the right place to start. I had no real anticipation about what the work would be, but after seeing the history recorded through Castle’s drawings, it really made sense to make the first paintings in the shed.

What is your draw to domestic interiors?

There’s a lot in the spaces that we live in on a daily basis that start to reflect how we feel inside them. I’m really interested in the space as a silent observer, one that tells the story of all the inhabitants who have passed through it. Also, how we move through space and what’s left over after we leave.

What kinds of things are left over?

There’s the legacy. Castle did not have verbal language and that opens the work up to people projecting onto [his legacy,] trying to make it fit some narrative they aim to spin. Not having a first-hand account of what his work was about is really an interesting and dense part of his story.

What are some ways you feel people may have projected their own spin onto his artwork?

I think people might feel the work is childish, like the figures or the collages. They may make assumptions that the work is easy and question ‘Why are we spending time looking at this and why are we giving it value?’ That’s one way to look at it, but it’s more interesting to imagine what it’s like to live in your head without language and to exist in a place before words and to make visual work from there. It’s impossible for a person with language to [imagine.] It’s dismissive to say that his work is childish or simplified.

That’s a really good point. Did you ever walk around the property wearing earplugs, to experiment?

No. [Laughs] I didn’t.

We should do that.

That’s definitely one way to do it but my thoughts would still be in the form of language or I would only recognize those thoughts, I think, once they’ve become language. In Castle’s case, having never heard sounds, try to imagine your mind without that foundation.

Right, because me putting in earplugs—if I see a dog barking, even though I can’t hear it, I can imagine what I would be hearing.

And you know the name of that thing; ‘dog.’

Right, and I can spell it and I can come up with a cultural symbol for the word ‘dog’—James Castle’s work has a lot of personal symbols. Oh, this is really interesting. I think I’ve really taken his work for granted, just as you said.

What’s really incredible about the house and the project, is giving people the chance to spend time with his work and treat it with respect. With the Castle work, once you dive in, it opens up to another world and gets deeper and deeper. It is very rewarding if you’re able to give it the time.

What inspires you?

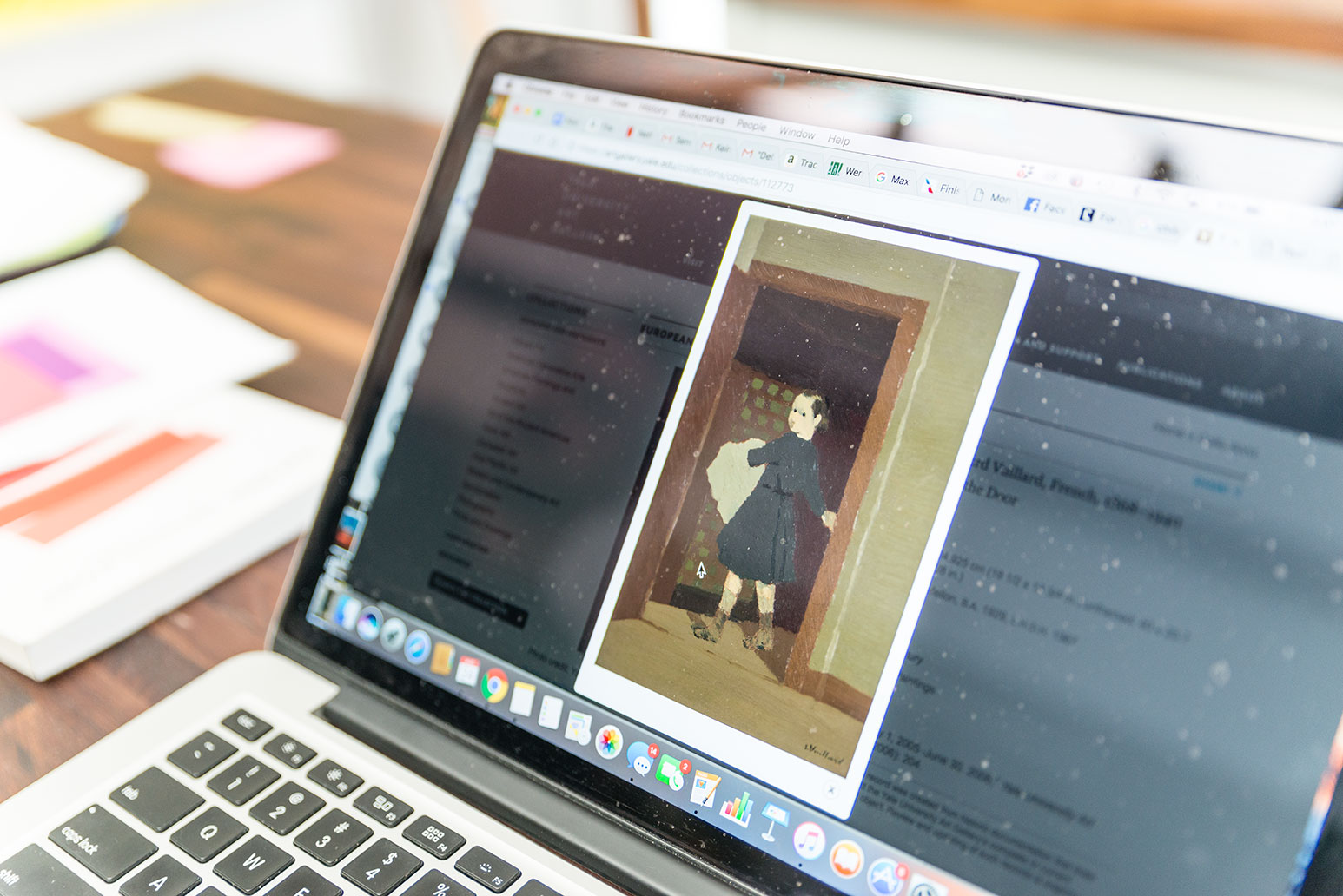

I really love Vuillard and Bonnard, who are both French painters from the late 1800s. Vuillard painted a lot of his mother sewing. She was a dressmaker and a corset maker, and he would sit and paint her working. They are tender paintings, often casual, calm settings of rooms with wallpaper and figures. They’re familiar and simple. In graduate school, I had an assignment to look at one painting for an hour.

That’s a great assignment.

It was amazing—and it was a class on attention. At the Yale Art Gallery I picked one of the Vuillard paintings. I’d seen this painting when I first got to school, just turned a corner and saw it for the first time. I was kind of knocked over. It’s only a twelve-inch painting. It’s super-small on cardboard, it’s a child going through a doorway but looking back at you as they pass through the doorway, so you’re kind of invited to enter into the painting with them almost like they are waiting for you.

It’s a pause. You’re describing a pause. And a connection between the figure and the viewer.

It’s a huge pause, which I think is rare. So, I went back and looked at it for an hour. You go back and forth between looking at the image and what you assume the story to be, or how you fit into that story, then you go to the paint; how it’s made, the texture, the colors, then you go back to feeling your body standing in space.

Did your mind wander?

Yes, I would drift but then come back. I found at the end, when the hour had gone up, I had a really hard time leaving, because, especially with this painting, I really got to know it and it felt intimate. Also, being in the exact same place where someone else would have stood to make the painting, and where others have also stood to observe, I think that’s a strange, profound connection.

I never thought about that either. When I’m looking at artwork in the museum, I’m occupying the same physical area as hundreds or more other viewers before me.

And the person who made it.

You were talking about having a hard time leaving the painting after an hour, did you say good-bye?

In my head. Because it [depicted] this person in the doorway who was waiting, constantly waiting but never leaving. I had to be the one to leave. It was an intense good-bye. I left, I turned around, I came back for a couple more minutes, then figured I had to walk away.

How weird is that.

It was really weird. I’ve never had that full experience before.

That’s my new bucket list item.

It’s really valuable because in a gallery, or museums, you usually feel like you have to see everything and move through it quickly.

We need an app for that: the slow down and look at art app. No, maybe that goes against the intention. What is your typical schedule?

I usually paint at night. I go to bed at two or three in the morning.

That is really late.

[Laughs] I like it. It’s calm at night, especially out here. It’s so quiet.

Did you have the doors open so you can hear crickets?

I had the doors open. You could hear the crickets. It’s a really amazing flat sky at night and it’s so quiet. Across the street, I was hearing a phone ringing every single night at the same time. It felt like a really old, like, ‘brrringgg.’ And I wasn’t sure what it was. But I went over and noticed it was the sprinkler hitting a metal pole [laughs], so that’s what was making the ringing sound. It was satisfying to know, but it also broke up the aura.

Are you painting outside as well?

I had been making a series of five paintings from right outside the porch at the intersection of Castle and Eugene. I was making a painting at different times of night on different days. I made one at nine o’clock, ten o’clock, eleven o’clock, midnight, and one A.M. on different days, just recording the light as it changes.

And the atmosphere? Probably a lot of smoke in the air.

Yes, the haziness, or if it was after a storm, or if it was really clear that day. It would all have a different effect, it was an act of looking and observation. But time passes completely differently when painting.

Faster or slower?

When the work is finished it feels like no time passed at all, but while you’re in the moment, it feels like nothing else is moving. It’s both fast and slow. What’s strange is that record of time is in the painting too. It stays light here for so long and it’s such a luxury to make paintings outside.

I’m so used to it that I forget. In summer the sun is out until 10pm.

I’m not used to it. Something else really different here is how light looks and how colors appear because of the lack of humidity. I’m used to New York or Toronto, where you can feel, like, the haziness between things. I know now it’s getting a bit smoky, but early on this summer the light would be very sharp, clear, and intense. Something that I wasn’t used to at all.

I need to get out more.

Also with distance, going up to the mountains a little bit and seeing distinctly how things get bluer and colder and darker as they become farther away, you can really trace the amazing idea of distance visually. I look at the foothills in the evening and they turn pink for about ten minutes, and they really glow. I remember the first time seeing that.

I feel like I’m seeing it for the first time through your eyes. It’s refreshing.

[Laughs] That’s what is really valuable about residency programs: being able to go to a place you’ve never been before and jump out of your world and your habits and your routines. To completely remove those things and start in another place, it allows you to immerse yourself and notice what is specifically different on a daily basis.

I want to talk about Yale. You went to graduate school there, which is like a holy grail of schools. Congratulations on that! How was the application process?

Thanks. The application was really intense. I hadn’t planned on going to grad school. In my senior year of undergrad, I submitted an application to Yale and that was the only school I applied to. I was expecting to take some time off, but thought, “May as well try, see if I get in.” For the application I submitted twenty images and afterwards I didn’t think I’d hear anything back, then a couple of months later, “Please come out for an interview,” so I was a little shocked.

I have to admit I’m a little irritated that you didn’t even apply to other schools. You did it on a whim, then were asked to come out for an interview.

I know. [Laughs] For the interview process I had to bring six paintings in person to the school, so people from all over the world are shipping in artwork. I don’t have my driver’s license, so I had a friend rent a truck. I have a motorcycle license but not a car driver’s license in Canada or the United States. Living in cities, not having a drivers license was never much of an issue, but I am thinking about getting one just for moving my artwork around.

Especially as your paintings get larger. What happened with the interview?

We rented a truck in mid-town Manhattan. My friend had never driven a truck before. We pick up the paintings, go up to the school, do the interview, and I think it goes horribly—it’s just stressful, like “Why are you here?” “Are you too young?” “What do you make paintings about?”

Were you younger than an average graduate?

I was the youngest in my program. I was twenty-one when I applied.

That is pretty young.

There were questions like, “Why not take off time? Why do you want to do this now?” And I didn’t really have good answers. Afterwards, I’m feeling overwhelmed and confused and just writing the whole thing off. We’re driving back. I’m navigating, and [the map is] telling us to take this parkway but trucks are not allowed on the parkway, but, okay, we go for it and then we’re coming up to a bridge. It’s a low-clearance bridge. We’ve go six paintings in the back and we’re coming up to the bridge and we have to get to the middle of the highway to get underneath the highest point of the underpass, and we make it. But then we see another bridge coming up and we get through that one but everyone’s honking at us. It’s getting dark out when a cop pulls us over, and [laughs] he’s, like, “What are you doing?” And we are just freaking out. “We have no idea what we’re doing. Please help us.”

[laughing]

“I’m an artist. I don’t drive.” He escorted us, seeing that we were very flustered, off the highway and we had to figure out another route to get back. [Laughs] I won’t forget that day. It was a couple of weeks later, I guess, that I got an email saying I had gotten into the program at Yale.

What a roller coaster! I like that you used ‘I’m an artist’ as an explanation. But after all that to receive news that you were accepted into the program!

Which was wild. I was there for the two years, from 2014 to 2016. It’s an intense program. Critiques every semester and final reviews. There’s twelve faculty and about seventy students who participate in critiques over three days. You’re going one after another all day. It just creates a feeling of anxiety for everybody, all the time.

I had a similar experience. I’m glad to hear I’m not the only one.

It’s a rough state. [laughs] It’s not enjoyable.

Let’s say you could go back with the knowledge you have now, what would you do differently?

I think I would have tried not to let studio visits influence me as much as they did right at the beginning. Maybe take a year or two off to get the foundation of a studio practice outside of an educational institution, that would have been helpful to do before being shaken around a lot [at the university.] I remember the first week getting there, you have a studio visit, someone tells you, “You shouldn’t be making this work, you should be making this work,” so you say, “Oh, of course,” and follow that advice. Then, two days later, someone else comes in, “Why are you making this?” It was basically like that for a year until I learned to effectively sort out those voices and read the intentions behind them, or learn who has a stake in what type of work, and how to navigate that.

I would agree. I think it’s a lot about sorting out what is going to actually serve your vision, and trusting your vision first.

It’s really hard when it has so much to do with your own work and something you’re close to.

It is really hard. Why painting for you? When we talked earlier, you said ‘touch’ and ‘sensuality’ in relation to the act of painting.

I think touch and sensuality are inherent to the medium—I’m interested in it as a very liquid substance that gets moved around, mixed, dried.

Kind of like spit and soot?

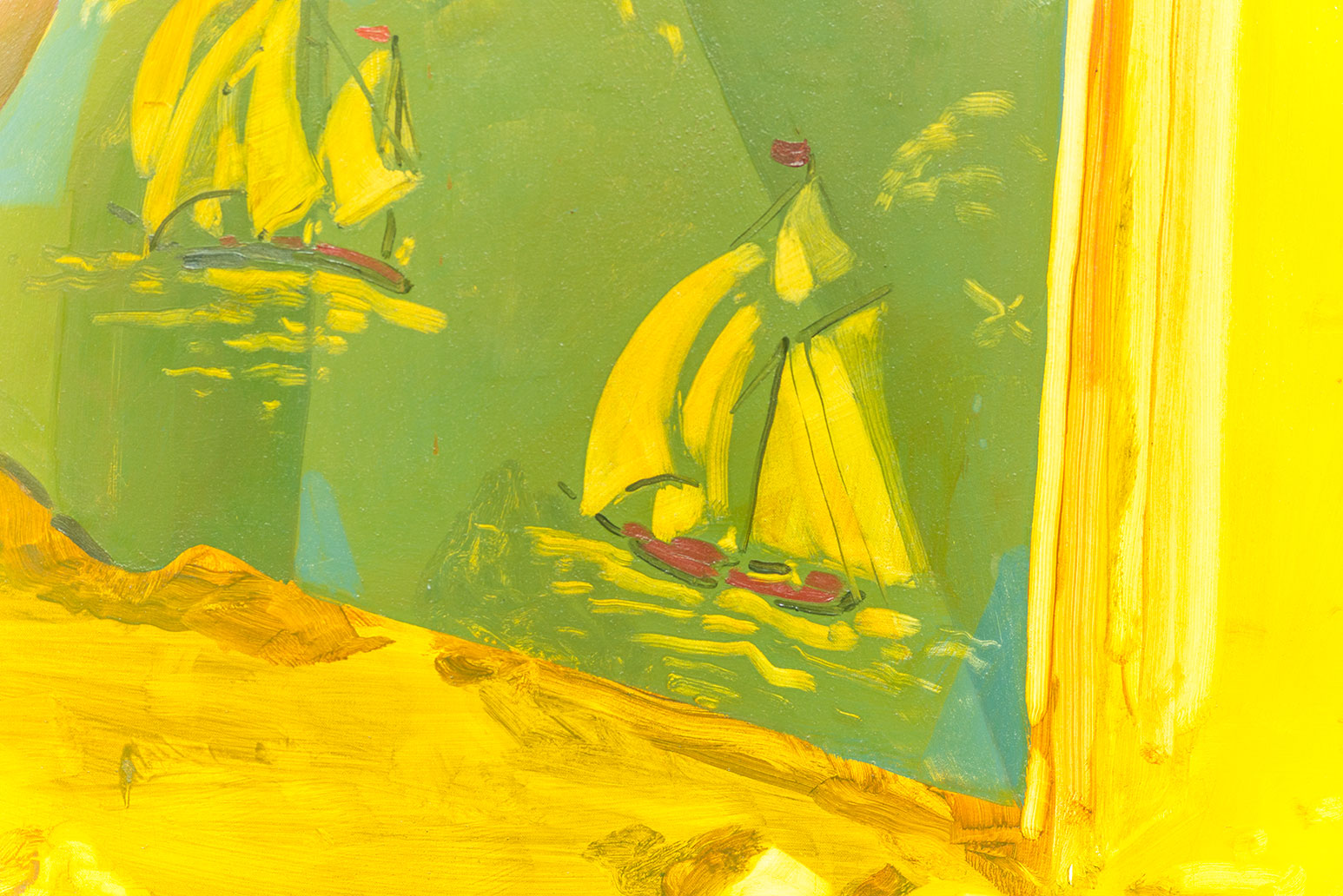

Exactly, Castle gets it—I mean, that’s a very basic form of a binder, spit and pigment. But the paint itself—some paints are transparent, some are opaque, some are flat, some are gritty, some are buttery, some are, like, crunchy. They all have their own characteristics and those [textures] are such a part of the process. I think it has a lot to do with touch. I think the [physicality] with which you apply the paint has a way of affecting how it appears on the canvas. So, if you make a really quick, hard mark, I think there is a way for that [gesture] to be felt by someone just by looking at it.

That’s subtle, I’m going to look for that in paintings, or try to sense it, I guess.

It has something to do with touch—how we understand touch on our skin, how we understand touch on our bodies.

I can see that when I’m looking at your work, because the brush strokes are right there, front and center, for me to look at. You are not painting in such a way to make the brush strokes invisible.

I think not tricking is important—for me, at least. To show you how the marks are made, show you the speed of certain marks, and when to slow down.

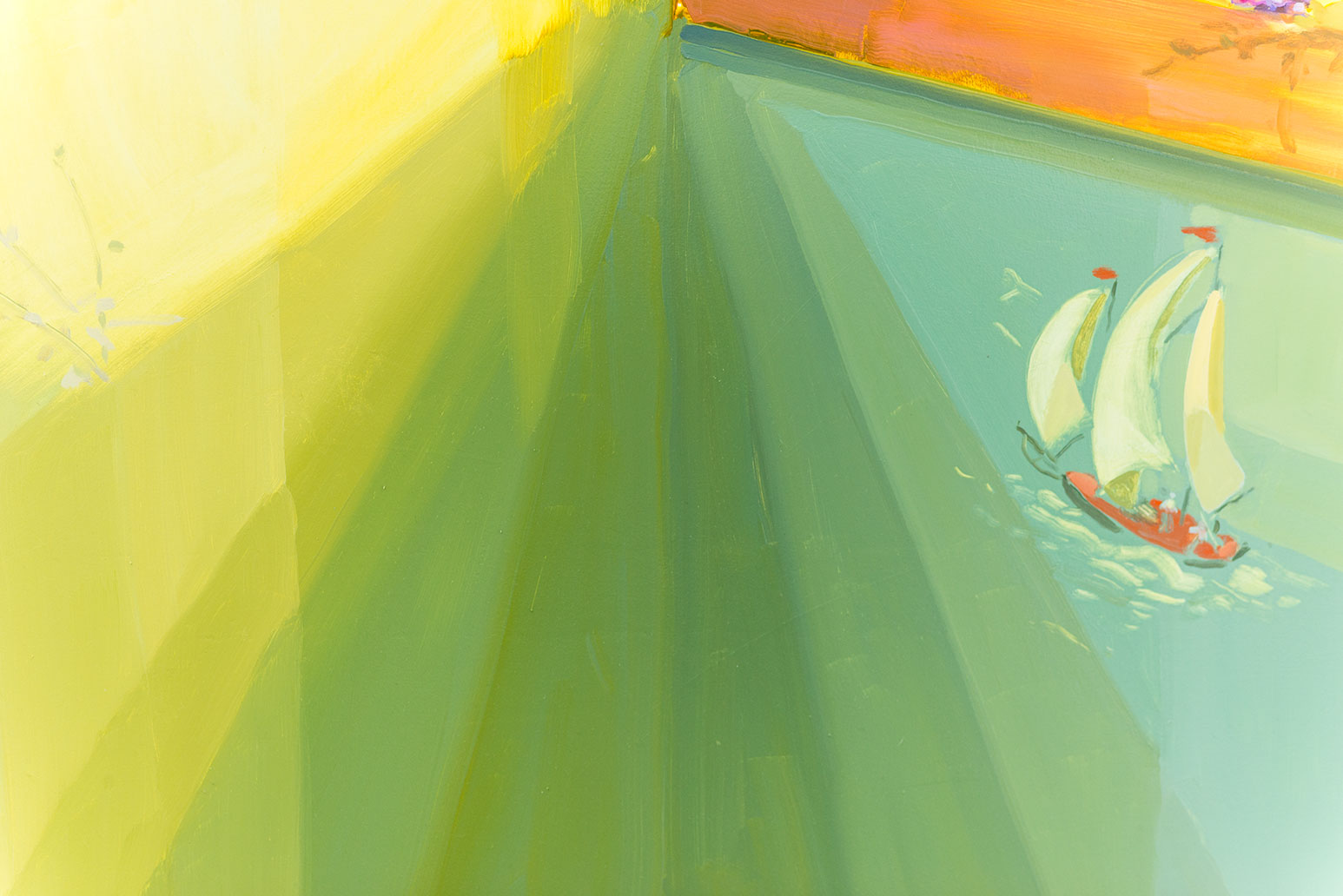

Let’s talk about this painting, after Edward Hopper’s “Sun in an Empty Room.”

Edward Hopper made these paintings right towards the end of his life where he painted basically sun coming into these empty rooms. They are empty rooms that are letting space in, and they depict a passage of time. I think they’re just really incredibly strange and beautiful. I was thinking about that when I started making that painting.

I’m going to have to think more about what it means to let space in a painting. What about the colors you use?

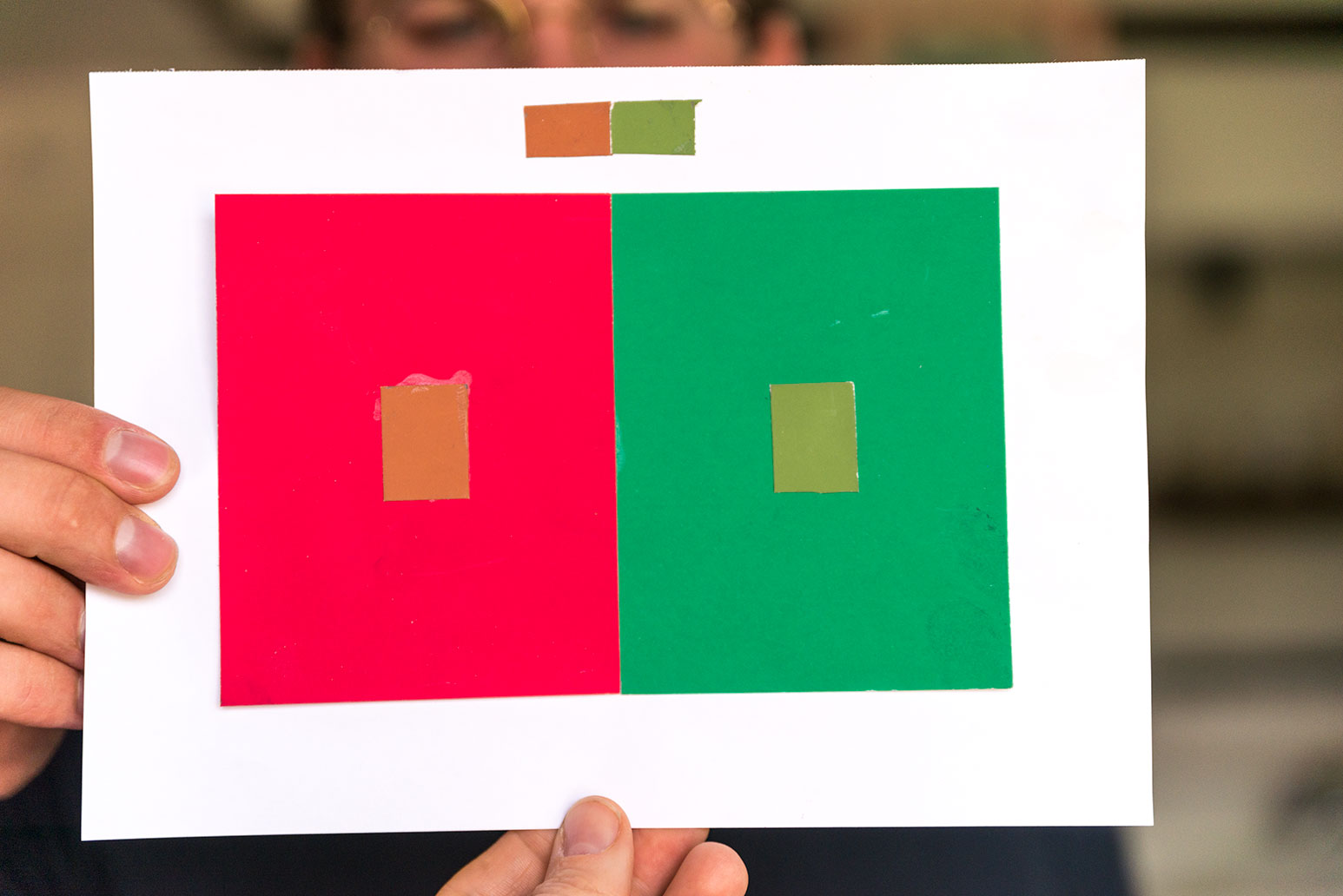

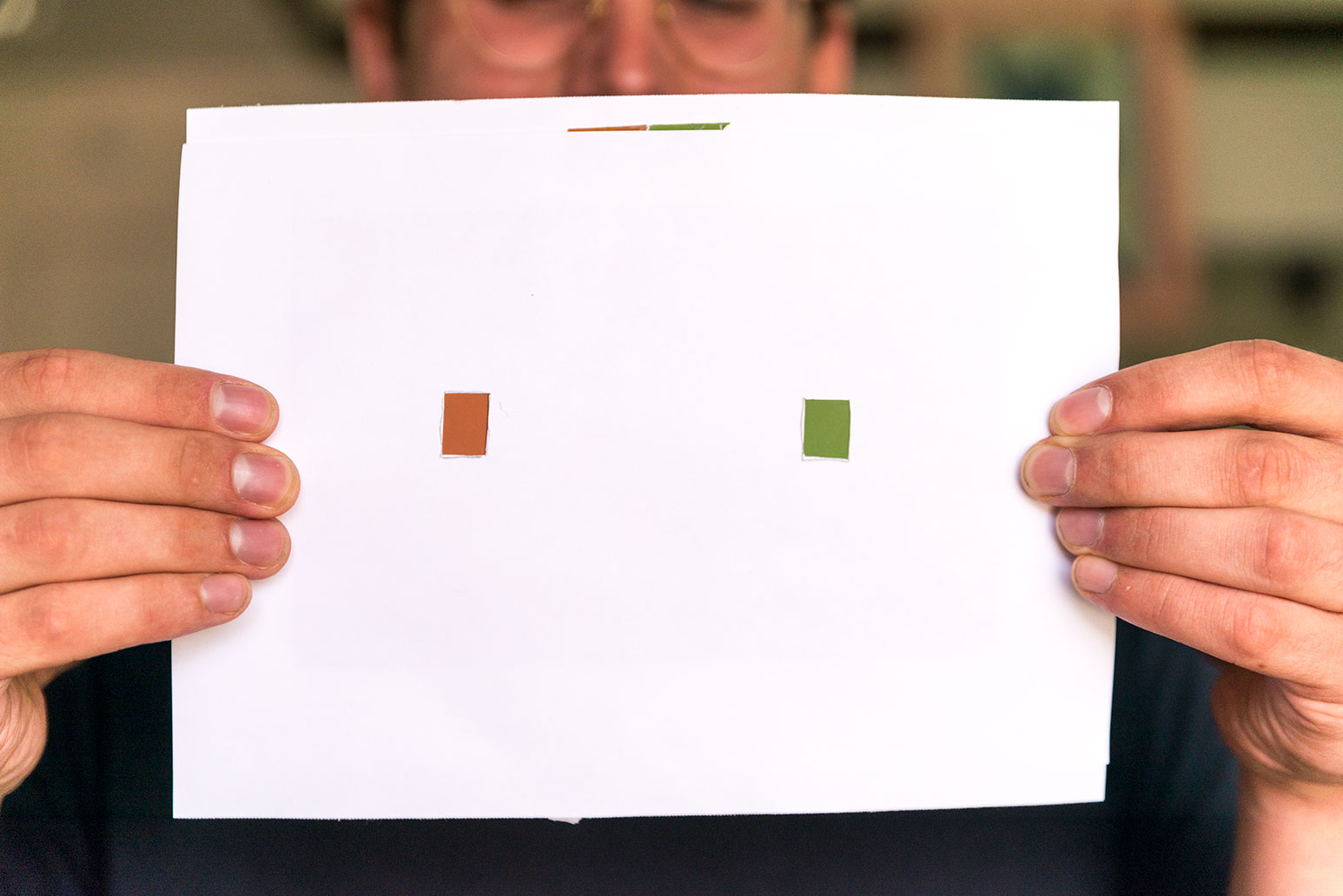

I use a pretty restrictive palette, only between three to six colors. Like a cold red, a warm red, cold blue, warm blue, cold yellow, warm yellow. I can mix the grays—it takes a lot to mix the grays, but when you can scrape them out, it leaves an undertone of all the colors that went into it, so you’re revealing those undertones in the process. Revealing the underpainting is a moment of excitement—I can scrape up the transparent areas and reveal light in a different way than trying to paint light into it.

So it’s a subtractive process?

Yes, I’ve done mostly an additive process before, trying to create the perception of light through color shifts, but, as you can see those scrapes with the dappling light, those are reducing the paint instead of adding it.

What do you think is the relationship between technique and content?

I think they need each other.

They do.

They affect each other. One can’t be separated from the other. How you make it is also what it means. I think the form and the content are inextricably linked. If you don’t have the vehicle to deliver whatever the content is, then it gets lost and you end up explaining things more than you have to. I think paintings should stand by themselves, be able to hold themselves up.

What about artist statements?

It’s kind of how I was talking about the Vuillard painting with the child in the doorway turning away and having that feeling, that feeling is not because of what the artist said the work is about. That feeling is because you are receptive to what is there on the surface and trusting yourself to look and trusting how you feel. I’m really interested in opening up the space where I’m not telling you what I was thinking about or what this painting means to me. I don’t think it necessarily matters and it’s going to be completely different for your experience. The same way with language, as soon as you’ve named something, you assume to know it. Remove the name and you open yourself up to looking a lot harder. I think it’s valuable to be perceptive and sensitive to the spaces we’re living in. I’ve been thinking about it more since being here with Castle’s work and learning more about him. Like in art school: you are drawing an apple—but as soon as you say that’s an apple, you begin painting from the idea “apple” that you have in your head. Making observational paintings is a lot about removing the name and looking at what is right in front of you.

What kind of advice would you give to emerging artists?

I think what we were talking about with trusting the work.

Trusting the work. Okay—How about something that’s really practical? Because trusting the work—

Is hard to do.

It’s a little harder to do.

It’s soul-searching.

Soul-searching, exactly. How about something less intense?

I think, make an effort to go to everyone else’s show and be really active in your art community.

Are we talking about networking?

I don’t think it has to feel weird and, like, icky, because it doesn’t feel good to do that.

You mean networking for the sake of networking? Yeah, I hate that.

[Laughs] I found where I’m at in New York there’s a lot of painters whose work I really love and I’m excited to go see their shows. It’s comforting to be a part of a group. Not that we meet up or anything afterwards, but it’s more about being engaged and involved in a conversation with people who are making work at the same time you are. I try to go see almost every show that’s up and go check out artists’ studios to get to know people.

That is beautiful advice.

I think it leads to other things. If we’re talking about opportunities, people will then recommend you for something because they’re aware of your work; because you came to their show, they’ll come to your show. It’s a natural way for that to happen.

Allowing yourself to naturally gravitate toward artwork you love and being confident in meeting other artists. You make it sound so simple!

I think it has rewards and repercussions that can be beneficial in unexpected ways.

But sometimes it does take getting out of your normal routine, or social bubble. Do you feel you’ve overcome some of that perpetual anxiety from graduate school?

I think what I’ve learned is I’ve just got to focus on what I can control, which is making the work and basically trust that the other things will come.

You are amazing. See, this is what I could have learned at Yale.

North End

January 10, 2019

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.