Creators, Makers, & Doers: Suzanne Lee Chetwood

Posted on 1/29/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

Suzanne Lee Chetwood has been painting the Boise Foothills for well over a decade; her aesthetic uses vibrant colors and pays close attention to the effects of those spectacular Idaho sunsets on highlights and shadows. She paints in one studio and works with ceramics in another, throwing pots on the wheel and making jewelry. But she will tell you her work is so much more than brushstrokes and clay. If you take her artwork home you are receiving a dose of healing energy, of lightness and love, and something we call Suzanne power. What is Suzanne power? It’s a force of energy towards true authenticity, it’s a walk in the shadows and in the light, and it’s filling up her cup as well as yours. We came away from our talk with Suzanne felling a little bewitched; dizzy with the depth of her story and vulnerability as she shared the crux of her fear and the elation of claiming power over it. We’ve never before heard a story about fire, darkness, and the color green quite like this, and it left us speechless.

So, there’s pink and orange and purple everywhere in here.

And my lipstick matches. [laughs] Obviously I love every color. I’m insane, crazy for color, like, “Give me the rainbow!” But if you ask me my favorite color, it’s green. The pukey one: chartreuse combined with barf. I love it.

Chartreuse barf. That’s a good color. [laughs] Were you crazy insane for the rainbow as a kid, too? I mean, I kind of think most kids are, but—

My earliest memories are hanging onto my Dad driving the car, looking at the sunset. I couldn’t read, but I wanted to know the language of color. That was my first language. I was like, “Dad. What colors are in that sunset?!” I have such vivid, colorful memories. I always knew I was going to be an artist, there was no question, no doubt, no stopping me. I had an impulse to communicate and it came out through drawing on the walls.

Did they support your creative energy then?

Yes. My mom knew I needed to touch things to learn. I struggled and I was diagnosed in the 70’s as being delayed in my learning abilities. I had different ways of learning. My mom always believed in me and [told me] I was super smart. She knew I needed to hold things, I couldn’t understand letters until I could hold foam letters.

You would have done great in a Montessori setting. Talking about color as a language makes me think of that phenomenon, what’s the name? When you hear a sound, but you also see the sound as a color?

Synesthesia, how some people hear color, taste sound. That whole cross wiring in the brain is a gift. Like all of our cruxes in our body and soul, our challenges in life come with a gift. I always refer to people and experiences as the pendulum.

Okay, so, you are waving your hand back and forth like a swinging pendulum on a grandfather clock. And that’s like my life, or my experience?

Yes. This is general populace. [waves hand]

It’s like a Bell curve?

Yes, but I’m here [swings hand wider.] And for a crux, issue, or whatever you want to call it on this side of the pendulum, there is a gift that swings so much higher on the other side. The blessing and the curse.

What’s your blessing and what’s your curse?

So many. My pendulum swings very far. So with all of my health challenges comes my experience of color and creating art that heals pain. My spine is very curved; scoliosis, stenosis, kyphosis; that pain forced me to deal with it by taking three ibuprofen a day, doing yoga, being physically fit. The flip side of the pendulum? I have a really tight, fit body. My core is like something you would see in a magazine ad! [laughter]

I’m regretting we didn’t photograph that… So now, I’m looking across the room and I see your painting with the spine bones hanging down on it. You’ve been making those spines out of clay for years but now I hear you talking about scoliosis and it makes sense now, I didn’t get it before.

My goal in art is not to throw it in your face. I want the experience to be authentic to me, but in the shape of its authenticity, I hope it relates to your path and to your journey. You will have different words to describe it, but if you are connecting with the art, you need it. That’s part of your lesson and your personal story. That’s how I look at art.

That explains why people are attracted to such a wide variety of art and mediums. It’s what you’re ready for or needing, like if you need validation or if you are ready to see a reflection of yourself somehow. We go through all different stages in life and what you’re open to receiving and learning changes throughout.

Often, up until the point you have a divorce, or a child, or a terrible breakup, or horrible tragedy or loss, you have a very different understanding of the world.

Yes. Did you ever look at somebody and think, “You know what you need? You need some severe trauma to round out your personality.” [laughter]

I love that! Struggle creates really unique individuals that are quite colorful. I’d say, in regards to my children, my kids have everything. Do I have to make the willow bend a bit? You know, you have to shake the tree so it grows stronger and deeper roots. You break a bone and that bone comes back stronger…

Bend the willow. I struggle with the comfort some of us enjoy in our life, and that we take obstacles out of the way of our children. But those obstacles are what made you and me.

Right!

We have too much stability, Suzanne!!

I know! We aren’t hungry for food, we have good careers. We’ve got a house with all the comforts… I felt like I was, like, drowning in suburbia. God bless my neighborhood and my neighbors and where I get to live, I am so lucky. But I was so comfortable. And not that— I don’t wish anyone to be uncomfortable, but— shake the tree!

Shake the tree. And limitations are—

Learning opportunities.

I want to hear more about your pendulum analogy.

The pendulum has hang time when it swings to the top of each side. In that hang time there’s learning and grace. You catch air, you leave your body and levitate—you have an out of body experience. You [get bold] and break up with that abusive relationship: hang time.

I think everybody wants that little slice of time. I do. What is that? What is that magical… but you can’t have that hang time without everything else in between.

No, that’s probably why I would argue artists have a big swing on their pendulum. In that hang time is what’s maybe called the flow. I saw you photographing earlier and I saw you putting things next to other things that I wouldn’t have. But you captured the essence of that piece, my iceberg painting about my friend who is a sound engineer with the hearing loss, and you put it in front of a painting with sound waves, which is exactly how I feel about him. And that’s the flow. You were in your artistic moment, I was just witnessing that hang time. That’s the top of the pendulum. There’s so much non-authentic art that we create in the chaos of the back forth of the pendulum. But we have to produce the one in fifty that’s in the flow. Makers make because we are obsessive. Between all that chaos, you catch air and that’s the flow.

Is that also why you’re into rock climbing? Is getting to the top like that moment of hang time?

No, it’s not to get to the top. I don’t think of myself as that thrill-seeker. I am very controlled and calculated and safe. I am probably a little afraid of heights. It’s like anything, I was actually a born introvert and I forced myself to be an extrovert. The challenge is the same with climbing. Rock climbing did not come naturally to me. I realize now what I love about bouldering is the puzzle. I don’t like crosswords or things like that. But I love a physical puzzle. Like, this [rock face] is un-scaleable, and you try it and think: no way! Then after ten sessions, “I got this!” It’s elation.

When I think of someone sitting down to a table to do a jigsaw puzzle, they are using their fingers to place an object and find where it fits. You like the challenge of a puzzle that uses your arms and your legs, and you’re out in the environment. It’s an all encompassing physical puzzle. But you’re not a thrill seeker?

No, I’m safe. I try to fit in and do the status quo thing. It’s so weak. [Laughs] That’s a truth about me.

I weirdly aspire to fitting into the norm.

Yeah, me too. Probably because of our childhoods.

That’s what I was going to say: it’s because I wasn’t able to feel that way as a child. I felt like I was on the outside. Today, it’s like, “I think I can do this, I think I can just about achieve mainstream.”

I was on the outside too.

So you overcompensate in other ways.

Yeah, “I’m going to wear two matching braids on the sides of my head.”

Or, two matching gray couches!

Or two matching couches! [laughter]

“I can be symmetrical.”

Totally, “I can balance this” Look at me, I’m super balanced! [laughter]

What else have you learned about color?

I’ve learned color is powerful and has the ability to heal. All my memories are steeped in that synesthesia stuff: smelling, tasting, hearing colors. I was given the freedom to explore as a child. My parents did not have a house; my dad taught my mom how to build—She was pregnant with my younger sister when they built a house in the woods. We slept under the stars for that first year. The house was always being worked on, so it was no big deal to let your child draw all over the walls. Drywall went up, and I would just draw and paint all over it, then they would paint over that, then I’d draw all over it again. When the house was finished I remember taking a big purple crayon—I got in trouble but it wasn’t like big trouble. It was like “Oh! Here’s your canvas.” My first painting lesson was when I was 12; my dad set up a still life with a candle holder and a candlestick, very traditional. We worked on that oil painting for a while. He did one. I did one. After that, I pursued painting in every aspect I could, pushing around paint. At 16, I got an amazing opportunity to go to the Pennsylvania Governor’s School for the Arts (PGSA) on a full scholarship, at Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pennsylvania. It was the most profound experience. I left my family to go live in a college dorm; everything was paid for: food, art supplies. We’d wake up at 6 am and stretch, then work from 7 am- 5 pm. Each night there was a performance by all kinds of artists: dancers, photographers, theater, writers. I was exposed to opera for the first time. I still go back there! In my little artist heart.

That’s a tremendous award!

Yeah. I came home a new person and I was like, “What am I gonna do in my little town?”

What did you do?

Luckily, a miracle occurred! My ceramics teacher at PGSA said, “You won’t believe it! You have a famous, world renowned potter in your little town. He lives in the woods and he teaches at Juniata College! I became his apprentice, Jack Troy is his name. I went to college when I was still in high school then; I’d leave school and go to college ceramics classes with him. I will always love him so much.

Look at that amazing foundation!

I was really lucky. And in between that—we lived on 26 acres, eleven miles from the nearest, tiny town, Huntington, Pennsylvania, population 5,000. I’d paint on my deck. You can imagine the dense forest of Pennsylvania, the dense hills. It’s like the classic screen saver of tiered, green rolling mountains overlapping like ocean waves. That was the view from my balcony; I would set up an easel outside and paint and paint and paint. And watch Bob Ross, rest in peace Bob, I love you. I would stay up working till three in the morning in the pot shop, we called it that, Jack’s studio, then I would go to school at 6 am the next morning.

I want to hear about the time you spent sleeping under the stars… it had to have shaped—

It shaped who I am. I was about to talk about that. Because, earlier I said ‘I didn’t have a home’ but I did. My parents forged a home out from the earth. My experience was mine. They provided, and worked hard, and created this [experience] that could be misunderstood as. . . [voice cracks]

For someone looking from the outside, your experience could be interpreted in a negative way?

[nods]

But was it exactly what your little soul needed?

[whispers] Yes. It was magical for me. [crying]

So, my memories, as I cry-talk through this, were. . . moss, moss green, and the trees were my canopy, and the light coming through the leaves, and isolation. I didn’t have playdates or friends or neighbors. I had nature. Nature had me. That was amazing. I did a painting called Meat Eating, Wandering, Warrior Woman. And it’s about a four-year-old, naked in the woods, in the pitch, black dark. Probably holding a turkey leg, but it looks like this barbaric, huge piece of meat. And I’m powerful as f—. If you go into the Pennsylvania forest, it’s dark and spooky and you don’t know what’s out there. But I never felt that. In my memory, I felt the light of all things good. Whatever you call it: the earth’s energy, god, or nature; everything in me that was all powerful, and sunshine, and bright. I’d walk into that deep, dark forest while my parents were sitting around our campfire; it was probably made of pallets and crates of wood used for shipping, so big that you would have to lift them with a forklift, and it was a bonfire!

That sounds like a big fire!

It was a giant fire that could take down forests—I mean, you would never have a fire like this in Idaho. The flames would be leaping into the stars and the embers going up to the sky. And I’m walking away from that. Deep into the woods. I can go back there, that’s a big a$$ fire, I can find it at any time. But I wanted to lose it in the darkness. I felt so powerful in that. I knew there was so much love around that fire—my parents were there; they had worked a full day, my mom had three babies and was swinging a hammer up on the roof. They dug out the foundation, poured the concrete, did the electrical, they did everything… and they were happy. They worked hard. They didn’t have money, but they had jobs and they built our house, and at the end of the day, when I think of our easy lives and we get in our cars and drive to our jobs and we get home and we’re all cranky and (h)angry, I’m thinking, “I don’t remember a ton of food sitting around that [fire.] But there was so much happiness.”

That’s… that’s.. I hate my life!

Yes! Right? I want to run away to the woods sometimes. I want to take my kids to the woods and give them that experience.

When you were talking about the giant bonfire, and described walking into the night, what I heard was a combination of the security of knowing the love was there and that you could get back, mixed with the thrill of walking into the darkness, and maybe even into danger.

Yes!

It’s partly about the risk. And about trusting yourself. You were challenging yourself to see how far you could go, maybe?

And that’s the essence of me—cause look at me bouldering. That is not a natural, human thing, to say, “Let me scale this giant [rock] face! I’m going to go 75 feet up without a rope!” That’s a good thing to note, about one’s self. I suppose.

I want to talk more about the healing power of art. How would you describe that?

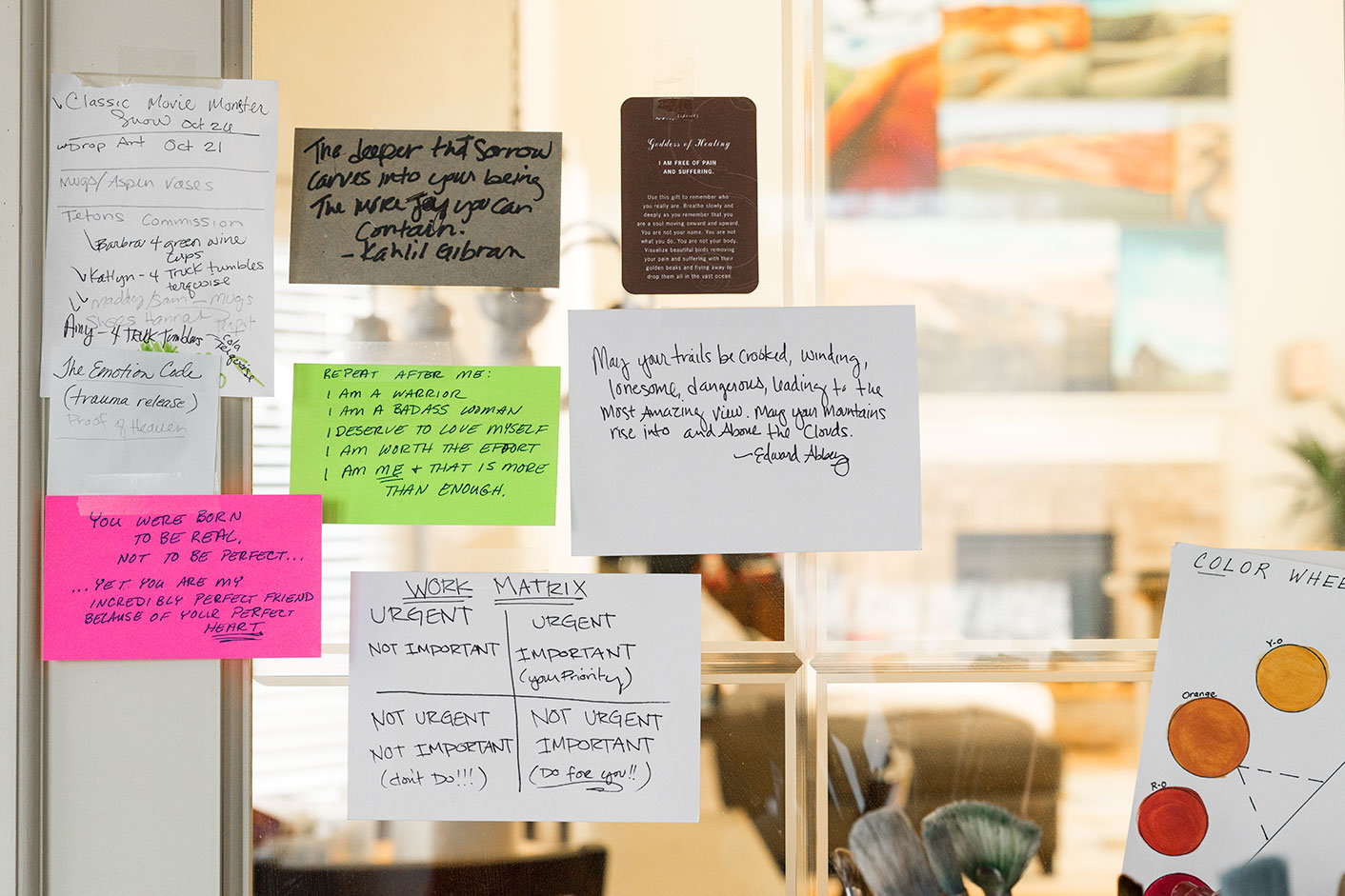

Many artists go to their aesthetic as [a means of] self-soothing. If you’re traumatized and you’re rocking your body [back and forth,] that’s self soothing. In the same way, you make music, you dance, you know, you speak words that come to you, or you sing them—I’ll paint them. I make my soul. It’s through the making [that you find] a zen calm. When I paint, I’m filled up, gathering light, like in my meditation. In creating, I am filling myself up. It brings me peace and love, even in the choice of colors and forms and shapes that I put down in the image. When you’re truly, deeply authentic (as I hope and strive to be some day), then everybody can connect to [your art]. What I’ve found with my work, is, when people connect to it that way, it changes their home. It changes their world. I love it! Friends will text me pictures, “I’m thinking of you, I’m holding your mug!” I put so much of my love, and energy, and healing ‘whoo whoo’ Suzanne powers into the painting and the pots because it’s filling me up, and then I give it to you. It’s like any good relationship; my cup is getting filled and I can’t help but fill your cup too. I truly, honestly believe my art is a healing vessel, all of it.

Your body is being healed through the process of making art and the art carries that energy with it, wherever it goes. We were just talking about this with Rick Jenkins!

Yeah, wherever it goes. That’s the truth for me, in my experience. It’s not something I planned, it just happened. And that’s my authentic experience.

Are you kind of a healer?

No, I am not a healer [in that sense]. I want my art to heal. If we can all heal ourselves, as individuals, and be that change, that’s the best way to save the planet.

Powerful words! What about the pressures we put on ourselves as humans or mothers to give, give, give? How does healing yourself fit within the context of parent guilt, or burnout?

Oh the guilt, ‘I am never doing enough.’ You want to give so much to your children. Just this morning I was thinking, ‘I don’t paint with my kids, I don’t draw with them enough! Here I am, with the world’s most perfect opportunity, and I’m busy doing my work. I’m working.’

That’s self talk in your head, telling yourself you’re not doing enough?

Yes, I have to justify that in my brain. I have to self-sooth and tell myself, “Mom works hard. Mom’s happy, and she does her thing.” I think it’s good for the children. Vivian, my daughter asked “Aw! Why are you getting interviewed again, Mom?! Why don’t they want to interview us?” I said, “You know what, honey? I’ve worked a long time and they want to know what I’ve learned and I’m being honored for that and if I make this space to do my work, then I will be successful. Then when it’s your turn, you’re going to have so much [support] backing you up, because I’m going to be stronger, and you will be even more successful than me.”

That’s like the difference say, between a parent making a cognitive choice, “I’ll teach you to be strong” versus “I will be strong, and you will learn and be supported by that for the rest of your life.” How would you tell people to start if they wanted to find that flow? If they are starting from nothing? If they wanted to experience the healing of making art?

That’s an awesome question because for so many people I think that [vacancy] is a source of a lot of depression in our culture. I mean, artists get depressed too, but I think that getting flow is bliss. The more we can have that and the more we can encourage it [the better.] So if somebody is interested in art: take classes! I teach Paint n’ Sips. Hey, hey, come meet me! I’ll sprinkle love all over you.

Yes, you will.

To get to the flow, take time for yourself. Five minutes, in between those two spaces of time that you do not have, make it, and just breathe. Think about whatever things are bothering you, or whatever. Find space, and eventually that will become time for you to [discover] an interest. And that interest becomes a meditation.

You’re like some kind of guru! Sometimes it’s even an interest that we had left behind, but maybe it’s waiting to be rediscovered. That also goes back to parent guilt and questioning whether we as parents are doing enough. You’re saying: carve that time out for yourself and it will make you stronger from the inside out. It will benefit everyone who comes into contact with you. Did you have to learn that the hard way?

No, I had that isolation growing up.

Of course! That could even be a body memory for you. A sensation that “Oh! This feels familiar, and good, and grounded.”

Totally. Grounded literally. Being outside grounds you. Take your shoes off, get barefoot on the dirt… all those horrible waves going through cell phone towers, and all the gadgets we have—getting grounded just pulls it right out of your body. There is a real physical healing with that.

What scares you?

I have fear. My fear comes from probably, like silly, benign childhood fears, like, I just want to be loved and respected and liked. It’s okay if I’m not, but that is a truth about me. I really want to be noticed.

That doesn’t sound silly at all. Or benign. The fear behind wanting to be noticed, could be, “What if I’m not seen?”

Yeah.

“What if I’m not valued?” I think that’s pretty scary.

Yeah, what if my art’s not good enough? What if I’m not a good enough parent? When I’m in the flow, I don’t have any fear of climbing rocks. When you’re doing a highball by yourself in New Mexico, like I was last March: I was 20 feet off the ground doing something very dangerous with no one around and I’d driven miles to get to this isolated region. That’s not who I am. But I was in the flow and I was fearless. I was powerful. I got on top of that rock and there was no one around to see me. And I loved it. So there I should have had legitimate fear. Worrying about all this other stuff, “Am I good enough?” Yeah, I’m enough. I’m hella enough.

Enjoyed this interview? Join us or tune in for Creators, Makers, & Doers: Live, a monthly series of informal talks focusing on the creative processes and studio practices of artists held at the James Castle House. Find out more by visiting our Events calendar. https://www.boiseartsandhistory.org/events/#/

South Boise

January 30, 2019