Creators, Makers, & Doers: Caroline Earley & Kate Walker

Posted on 9/22/21 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Caroline Earley & Kate Walker are artists, professors, and partners who work independently and together. Yes, both, in multiple capacities. We chatted about their move from New Zealand to Idaho and the contrast in teaching art there versus here. Actually, contrasts and comparisons came up a lot: How is your work similar? Different? What is a big “C” collaboration and a little “c” collaboration? What’s the difference between being a queer artist and exploring a queer aesthetic? What are your strengths and weaknesses? How about your partner’s strengths and weaknesses? (Yeah, we went there and everyone played nice.) Caroline and Kate weave together a creative life in which they each value connection and conversation in material, process, and people. It’s really quite beautiful. In Caroline’s words, “None of it was expected, and a lot of it was hoped for.”

How did you meet?

How did you meet?

CE: We met in New Zealand, both teaching art in high school. We met through Wellington Art Teachers Association. We were friends for a few years before we got involved. I earned my MFA in the U.S. then went to New Zealand in 1994. Teaching high school there is really a different thing than here, the high school seniors can choose from five art subjects: painting, printmaking photo, sculpture—

KW: Design.

CE: Art history. It was amazing to teach art there. A lot of professional artists in New Zealand teach high school because there are only five universities, maybe?

KW: Are there that many? One, two, three—

CE: There’s probably more than that now—

If you would compare New Zealand to an American state in terms of population, which state would it be?

If you would compare New Zealand to an American state in terms of population, which state would it be?

CE: Colorado.

That’s smaller than I expected.

KW: What is Colorado’s population?

CE: New Zealand’s five million now. It’s the land mass of California, but with the population of Colorado.

Caroline, how did you get to New Zealand?

CE: I was involved with somebody who moved to New Zealand. You never move for any other reason unless you’re going to school or something like that, I think.

Following a relationship, a job, or going to school? I see that.

CE: I think that’s most people’s story.

I think that might have happened to Kate, getting from New Zealand to here. [laughter]

KW: Yes.

Kate where did you go to graduate school?

KW: Tucson. Caroline and I moved to Arizona together when I went to grad school, so we’ve sort of been backwards and forwards. Then we went back to New Zealand because we were offered work teaching college.

CE: Kate taught the 2D and digital classes. And I taught on the 3D.

That’s something I find interesting, Caroline, you work in ceramics, clay, which is dirt, the oldest medium I can think of, and Kate works in digital media, an opposite.

CE: But some of my forms are digitally formed. There’s crossover there.

KW: We are both interested in things that aren’t proper.

CE: Subversive form?

KW: Yeah, that’s a good term.

Are there ways you work out of sync with each other?

KW: She’s more of a perfectionist.

CE: I’m more of a formalist and Kate’s stronger in terms of narrative and big ideas. She comes up with these big ideas and every time, [it turns into] this wonderful thing. Like when she wanted to make the big balloon.

I think of Caroline’s work as a very concrete, physical thing. And I think of Kate’s work as an idea embodied in a material. And that material could be anything. Such as a big balloon.

CE: My work comes from a craft standpoint, where the material is a big part of the idea. And how materials act on materials and how humans act on materials and how humans act on each other. That physicality is key for me.

How about you Kate?

KW: I start with an idea that might seem outlandish, then I figure out how to make it. Like with that balloon project, Cloudship, I had to figure out how to design an inflatable and make it float. How much helium does it need, what size does it have to be, all of that kind of stuff.

While you’re explaining, Caroline’s shaking her head, “that’s too complicated.”

CE: That part is okay, but I could never do all the talking to people.

KW: I spent months on email and on the phone, then there’s organizing the performance.

Describe Cloudship for us.

KW: Cloudship was a performance project and video that involved 13 performers walking through the Boise Foothills, parading an inflatable—the form was based on a cloud, and it had an engine component that was inspired by the nuclear plane engine on view down at the Idaho National Laboratory [INL].

CE: A plane prototype.

KW: So they designed a plane in the ’50s that would [transport] the president, in the event of a nuclear holocaust. The idea being that since the plane was nuclear powered, it wouldn’t have to stop to refuel. It would be able to fly for something like five or six days. I don’t know where they were planning to land in the Armageddon…. But you can go down to the museum and see, [for instance] what the menu that was planned for day one, two—

It’s an escape hatch.

CE: And a folly.

KW: They tested it up and down the INL with no nuclear containment. The toxicity was huge, probably immeasurable, because they didn’t even know about toxicity at the time.

Remind me where the Idaho National Laboratory is located?

KW: Out in the desert near Idaho Falls, Pocatello.

CE: Arco, that corner. Right on top of the aquifer.

KW: I was loosely thinking about utopian and dystopian ideas as being the flip side of the same thing, like, how those ideas form in popular culture. I was a child of the ’80s, and life was—you know, everyone had a lot of nuclear fears at the time, a lot of ’80s music was, like The Clash “London’s burning,” all that grunge and punk was really about the mood “We are destroying the world.” Well, that and some utopian thinking, “We need to find solutions.” They go together.

So you took the form of the nuclear ship designed as a presidential Armageddon escape hatch, and turned it into a utopian theme?

KW: Yeah, it was kind of both at once. It was a bit ambiguous. We did it at sunset.

CE: It was beautiful.

KW: I’m interested in things that are aesthetically alluring, but with an edge of uneasiness about them. The way I described [the balloon project] to the performers was to imagine “What if we were the last people existing on the planet? But we still believed it was going to be okay? And that we needed to launch this thing to survive.” It was like an offering, a prayer.

CE: The research—the organizing and talking to all those people all the time.

Hope in a hand-crafted floating balloon. Caroline, are you an introvert?

CE: Absolutely. Kate’s got a real social ability to organize.

To organize people towards a goal?

KW: I’m interested in collective action. I’m really interested in process, in having conversations. One of the great things about teaching is that I invite my students to participate—the performers are all people I’ve worked with, students and former students who often know each other, so it’s this ready‑made group of people who already have a dynamic, a rapport.

They have camaraderie?

KW: And working together does something more. I am really interested in community‑building. It’s a cliché, but these conversations and relationships happen during projects—I love all that.

It’s very dynamic and it’s more than the sum of its parts. Caroline, how would you describe your work?

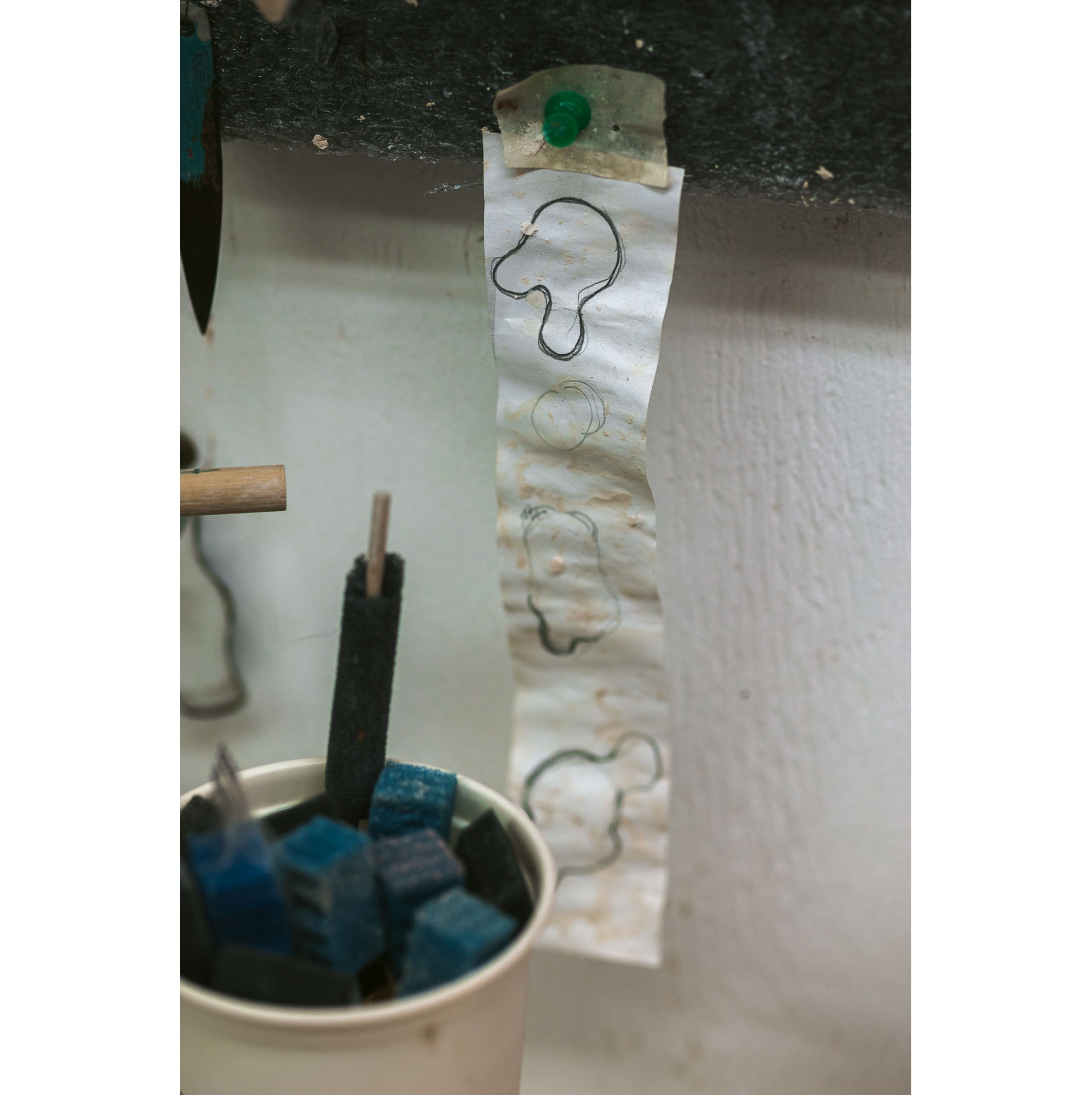

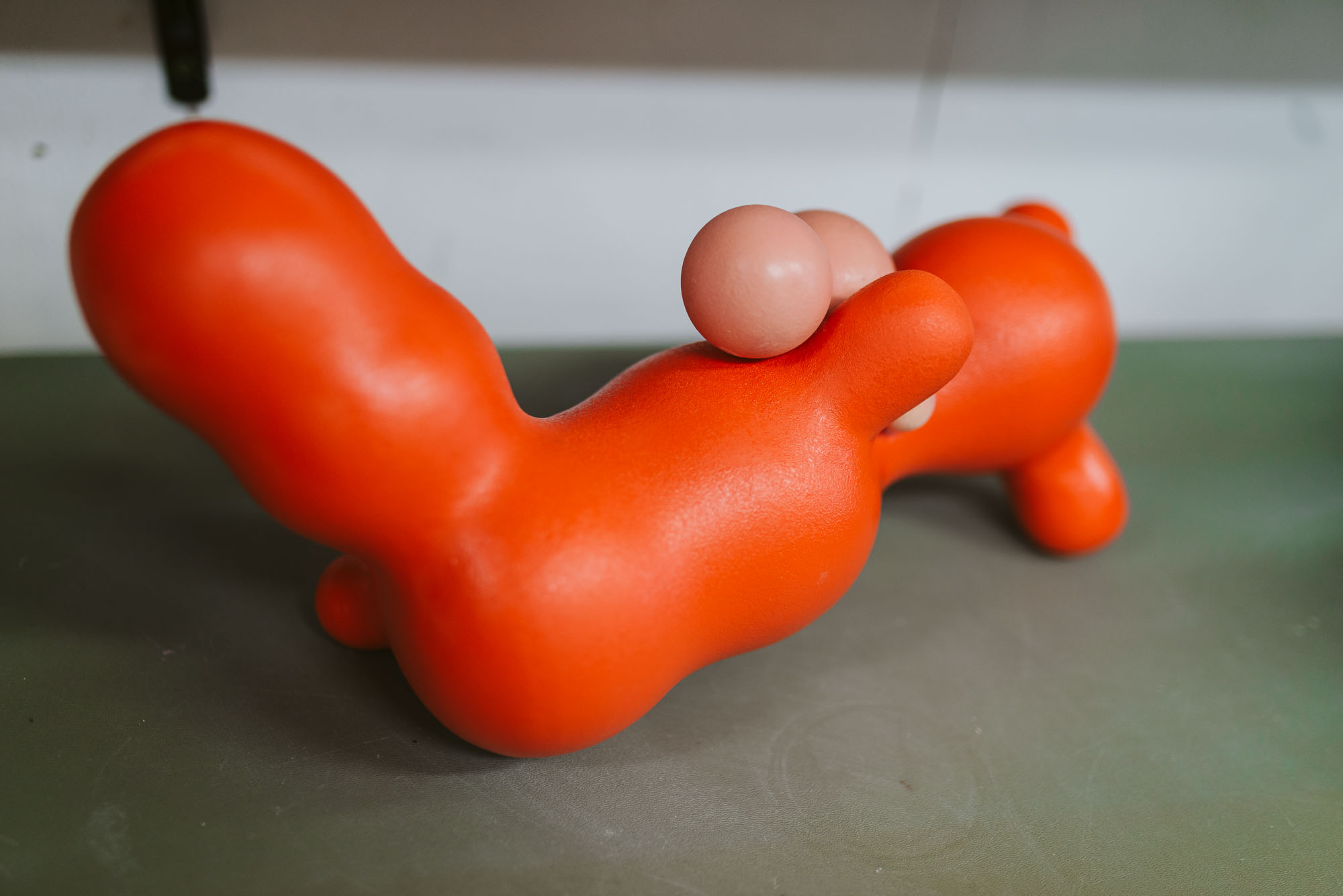

CE: I make these forms, about the size you can hold in your hand.

Pineapple size or melon? A gourd?

CE: Yeah, yeah. You can hold it in your hands or your arms. Actually, if you pick one of those things up, it drapes on your body

Like a baby?

CE: Yeah, like a baby. One of the things I’ve talked about in terms of how forms occupy space and how they impact each other, is similar to when you pick up a child who’s a bit too big for you to pick up, but you still do it because they’re asleep, like, you’ve been out to see fireworks or something, and you have to carry them into the house from the car, right; it’s that moment. And their body conforms to your body in a way that doesn’t happen any other time. Every part of their body is so relaxed it—

It molds.

CE:—to the body of the person. I’m interested in the dichotomy when a hard ceramic surface embodies the softness I just described.

Not just the softness, but it’s impressionable.

CE: And connectedness. That’s right. Trying to get the individual pieces of my work to feel connected although separate.

You also used the word appendage.

KW: A teapot has appendages: the spout, the handle, the knob on the lid. Basically, most ceramics is form and appendage.

CE: Even a mug is a form and an appendage. The way it works in your hand, the way it fits to your body. Ceramics is also really about the body.

And the vessel.

CE: Ceramics is described in terms of the body: a vase has shoulders. It has a waist. It has a foot. Cups are one of the most intimate objects we own; what else do you hold to your mouth every day?

A mug is also an appendage to your hand.

CE: I ask my students, “Is there a mug you drink your morning drink out of, whether it’s coffee or tea? And how do you feel when somebody else, your roommate, uses your mug?”

I think “They better not break my mug.”

CE: Yeah. You don’t really want them to use it.

Did either of you imagine you would end up living so closely with another artist? Sharing mugs? Both in academia, and with a studio practice?

KW: Go to work together.

CE: Organize our schedules the same.

KW: A lot of people need their own space and to have different lives. We’re sort of the opposite; we’re quite happy going off to work together and having coffee together and we’ll go to a museum and like all the same things. And the conversations, I think that’s changed both of our work. It’s almost like plugging your electric cord in with someone else, and their energy adds to your own, adds to your work.

How did you start collaborating?

How did you start collaborating?

CE: I guess it’s collaborating with a little “c” and a big “C.” the little “c” we’ve been doing informally for a long time.

KW: Giving each other feedback on projects, helping decision making.

How about big “C” collaborations.

KW: We had a visiting artist, Janet DeBoos, she’s terrific by the way, and Caroline was describing a project to her. I’d made drawings that Caroline used in her design.

CE: It’s the piece that won the Triennial, the big table piece.

I love that one. Domestic Disturbance is the title. It won the Juror’s choice in the Boise Art Museum’s Idaho Triennial in 2000—?

KW: 2013. So Janet said “You two should come do a collaborative residency at the Australian National University.” We said, “Yes, please.” We applied and we went. We experimented with lots of different kinds of collaboration.

Are the plates one of those collaborations? They are part of a larger work, Summertime Rose?

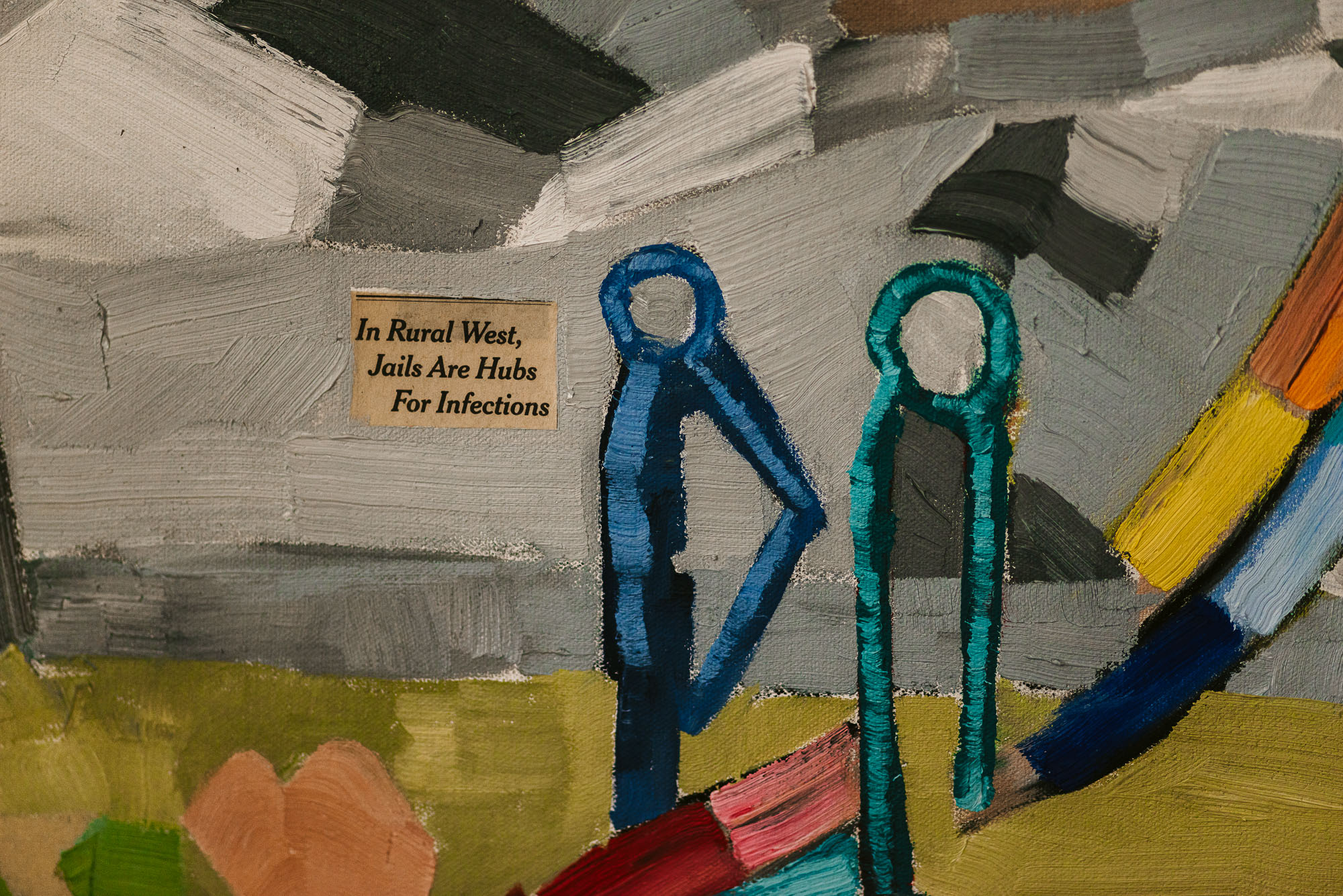

CE: Yes. The plates were found objects; some were purchased, some were taken from the [kitchen] at the residency; we matched them up with different colored ceramic decals. Some of the images come from Kate’s paintings. That’s really when we started thinking about disasters and putting that into our work.

Natural disasters?

CE: An aftermath sort of thing.

KW: We were also exploring what a queer aesthetic would look like for us, yeah, queer form.

A queer aesthetic?

KW: Like Felix Gonzalez‑Torres, he’s a conceptual sculptural artist who explored that in his work. His works are theorized as developing a queer aesthetic. During the ’90s, he was making a lot of work about his partner who died of AIDS. We were talking and thinking about the “same‑same” and subverting the modernist form.

CE: Subverting certain expectations that a viewer might have of what a form could be in terms of clay. You know, what’s clay allowed to be and what it’s not allowed to be. Those things have changed a lot since that project, and clay is allowed to be more things now. That work was early on in that conversation.

What’s a basic entry point into queer art for someone with no prior knowledge?

CE: I don’t know if there’s a queer sensibility. I think that’s different from an aesthetic of queerness, like building on the question “What is queerness?” Professor Harmony Hammond was a big influence on me; her painting deals with the ideas of “same-same,” it’s abstract as well.

CE: Homo instead of hetero is the “same-same,” and the questions “Where’s the difference? What does it mean to queer something? To make it other? To make strange? Not the dominant thing?”

Themes that might apply when looking at art made by someone who’s queer then, are “same-same” or other?

CE: Maybe somebody who’s interested in queerness as a conceptual concern. There are a lot of queer artists out there who aren’t interested in queerness as a conceptual concern.

I see now. Being queer and making art does not mean you are exploring a queer aesthetic.

CE: Many are, but some aren’t. Depends on the artist. Like Everett Hoffman and Adam Atkinson, they’re interested in queerness, in a more male queerness and a sort of sparkly focus on other things, exploring the visual language of queerness.

KW: I think also within queer art there is a big exploration and visualization of queer sexuality and gender expression and moving beyond the binary. A lot of exhibitions are explicitly focused on sexuality, but in ways that don’t buy into stereotypes. There’s so much visibility of heteronormative culture, well, what does the lens look like otherwise?

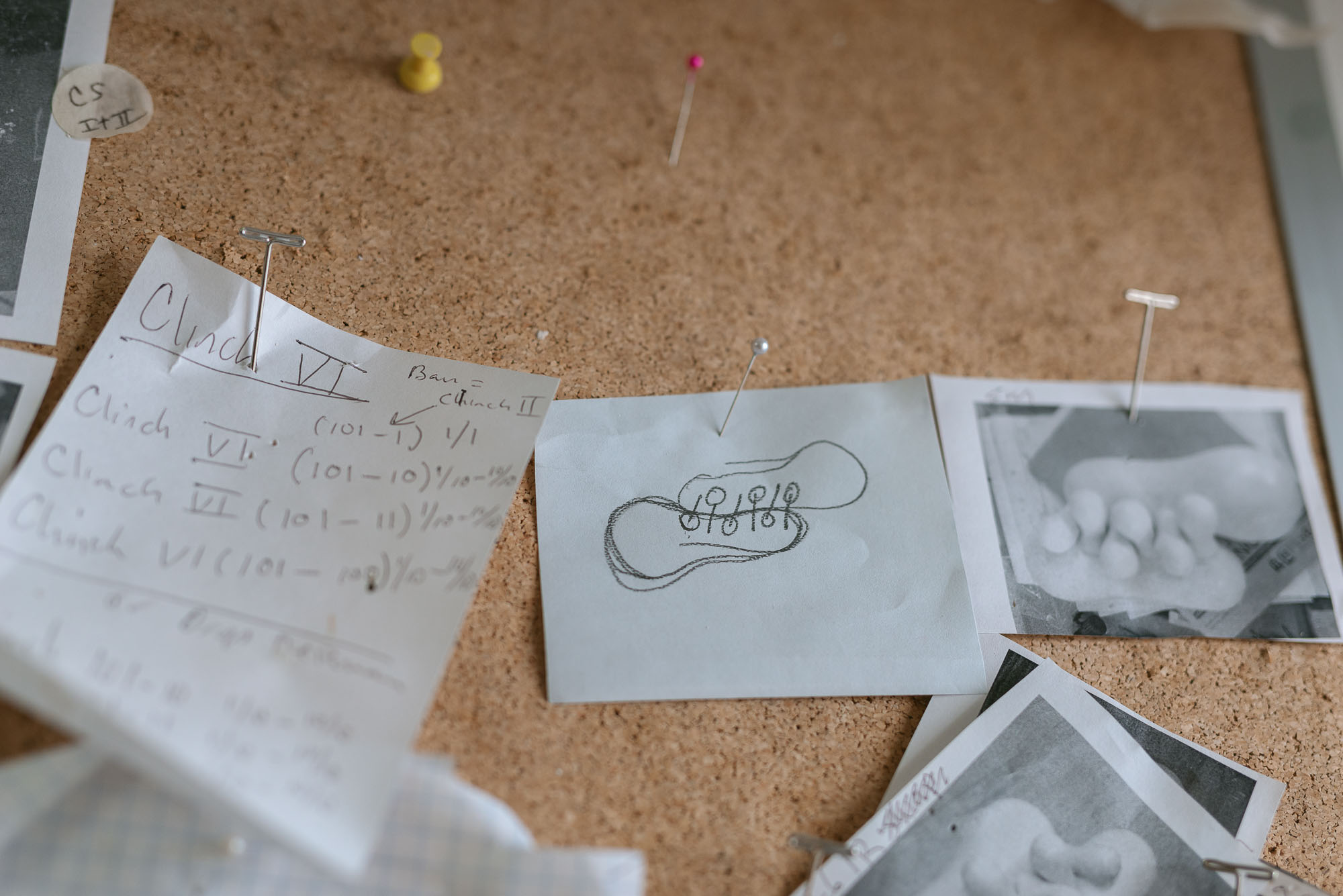

CE: Like our collaborative piece that hangs in City Hall, Intersexions VI-X, the shapes are chromosomal. That’s a conversation because one of the things that brought being queer into the mainstream was the idea that “You’re born that way, you can’t help it.” A genetic chromosomal science‑based thing.

An “acceptable” scientific logic to queerness?

CE: It’s problematic because it makes [assumptions about] people who have made choices to be in same‑sex relationships, or people who wouldn’t necessarily see themselves as biologically chromosomal‑driven, right? “You’re born that way, you can’t help it, so we’ll let you be like that.” It’s permission from the dominant culture allowing people to be how they want to be. I think we’re seeing younger people right now really push against that. They’re just living their life.

This mirrors the earlier conversation around what clay is allowed to be and what it’s not allowed to be. I see a metaphor now.

CE: In that Intersexions series, the images come from the “Add The Words” campaign. We came up with forms and chose images collaboratively. I physically made the forms and Kate produced the images.

Yes “Add The Words” Idaho. How did you get to Idaho?

CE: I got offered the job. There are other reasons too. I really wanted a chance to teach ceramics and not [general art.] And I had a sister, Sarah, with Down syndrome. My parents both died at the beginning of the turn of the century, and so—

Okay, hang on. In the 1990s. I haven’t heard it called the turn of the century.

CE: 1999 and 2000, my parents both died. I have a lot of siblings, so different family members helped to look after Sarah, but later in her life things started changing and it became compelling to come back and be a bigger part of her life. She came from West Virginia to live in Idaho in 2016. She died in 2018; she had dementia. We like life here too. We liked being in Arizona. Kate likes the desert environment.

I have an idea. I’m going to ask Kate to leave the room and I’m going to ask Caroline some questions just the two of us, then we’ll switch.

KW: Sure. I’ll leave first. [Laughter.]

(Break)

Caroline, describe some of your strengths and weaknesses.

CE: It’s funny, it’s the same thing. Discipline is a strength and a weakness depending on what the motivation is. I can just go, go, and go; when I’m in that mode, it might be 2:00 in the morning and I’m really tired, but I know I have to finish that thing, even if it means I’m going to be up until 4 a.m. I’m going to do it.

Kind of like with this thing, booking your trip back to New Zealand?

CE: Yes. This thing we’re doing, to get an MIQ voucher [Managed Isolation and Quarantine,] literally, every night from 10:30 till about 1:00 in the morning.

This is a good time to mention that Caroline and Kate are trying to get back to New Zealand before December and they have to book quarantine time, kind of like booking a hotel. It’s a government website that you check for openings. I’ll just say it: you’re obsessed with refreshing that screen, waiting for dates to open up.

CE: Nothing’s available all the way till the end of November.

So, the whole time we’ve been in the studios and during our conversation, there’s been this constant screen refreshing happening. And you’re going to get your spot, right?

CE: Oh, yeah, yeah. If it’s available, I will get it. A big strength for me is the ability to focus and persevere. But, also, if I don’t want to do something, I find it really hard to get myself to do it. I’m a lot like my dad in that respect; I mean, he was amazing. He put a zillion kids through college. But he was interested in what he was interested in.

What are you interested in?

CE: I’m interested in two things right now: the studio, obviously, and my garden. I’m learning a lot about growing my own food. If Kate and I were both trying to do something to deal with climate change, my way would be to regenerate my soil and sequester a load of carbon all on my own [chuckling]. I think I’m doing that.

And be independent about it?

CE: Yes, not necessarily join a group or a club or anything. Whereas Kate might make art that raises an awareness. It’s been a weird couple of years with the pandemic and trying to find where my motivation is and what I want to do. I’ve given myself a lot of time to transition into what’s coming next. I still don’t know what that is, and I guess a strength is being fine with that. I don’t have any looming deadlines. There might be a couple of shows I’d like to put some pieces in, or enter, but we’ll see if I get them done.

Acceptance for where you’re at right now?

CE: Yes. Also, I guess I’m not very good at keeping up with the business side of being an artist. Some people are really good at that.

Marketing?

CE: Marketing, communicating, making more and more opportunities for yourself. I find that hard to do. I get lucky.

What do you mean by lucky?

CE: Opportunities have happened that I don’t think I put a lot of work into making. I think, if you make the work, it can make the opportunities.

The work must come first. Opportunity follows. Have you been lucky lately?

CE: Yes, the other reason I need to get to New Zealand in November is that I’ve been invited to be a master demonstrator at a festival slash conference‑y thing in Australia.

Wow!

CE: But Australia’s borders are closed. I’ve been invited because I’m a New Zealand citizen and at the time of the invitation, they had free borders. So I have to go to New Zealand and quarantine first.

What is it called?

CE: It’s called Clay Gulgong.

What is that word?

CE: It’s a place. It’s a town—a woman named Janet Mansfield had a property there and she’d brought people in for this event for many, many years. I’ve always wanted to go. To be invited as a demonstrator is just a fantastic thing. There’s an exhibition as well.

Did you reach out to them?

CE: No, no. I got an email, they’d seen my work.

That’s so cool. While Kate’s gone, what would you say her strengths and weaknesses are?

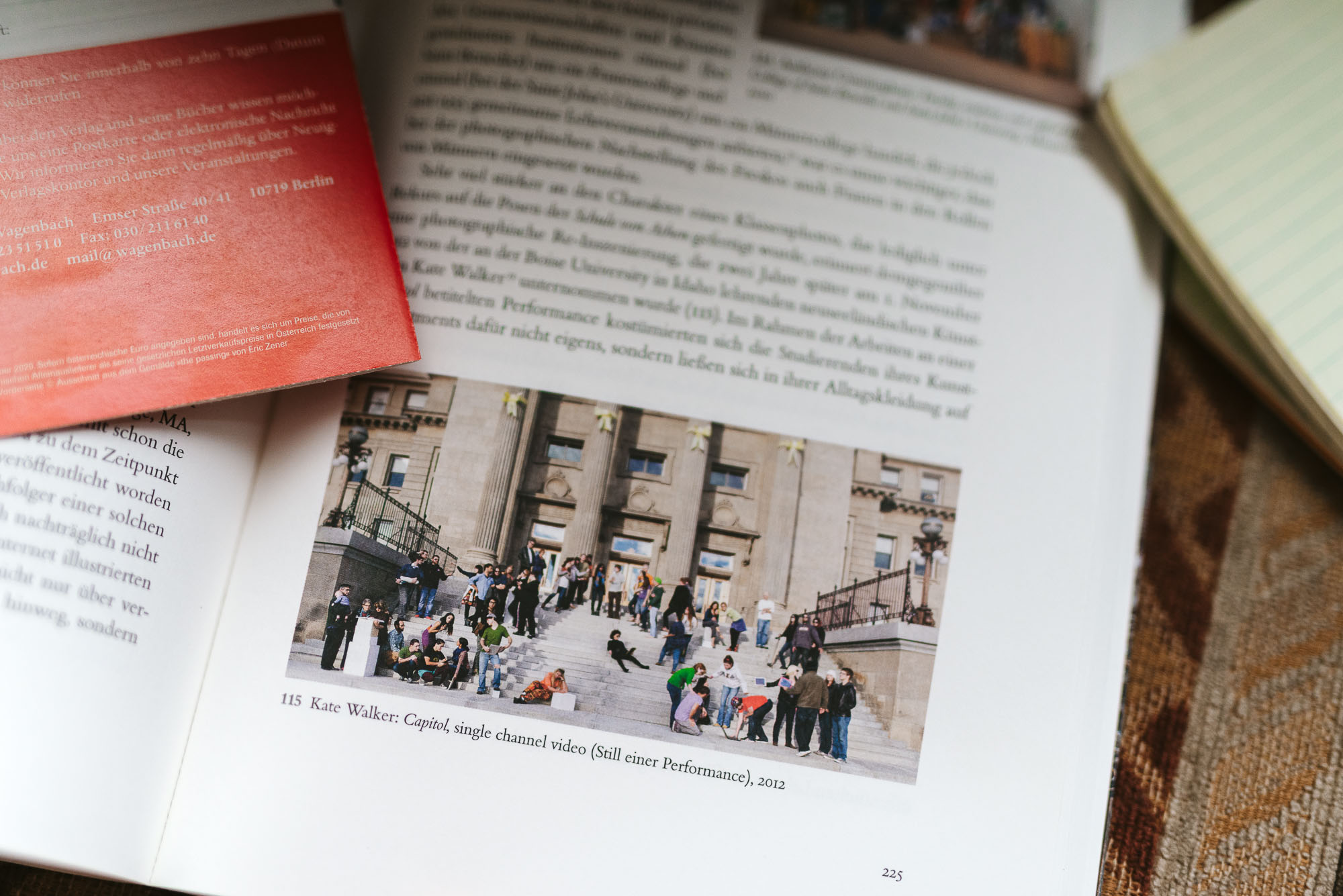

CE: She’s good at all those kinds of things I’m not very good at; keeping in contact with people, plus the ability to come up with big ideas. I don’t know if you know about the piece she did on the steps of the state capitol, re-enacting the School of Athens?

I do not. Her work is so intangible.

CE: Ask her about this when she comes back. She was teaching a big Art 100 class in the multipurpose building. And she watched as the students all got up and moved to their groups, for group work, and she just—moments like that can encapsulate an idea for her, whether it’s her Disaster Karaoke project or the School of Athens, or Manual of Arms. When we do collaborative work, we decided to each use our strengths. We’ve gotten the work into exhibitions because Kate would apply to the shows—

She does the paperwork and applications?

CE: She did all of that. Then I would pack the work to send.

Because she can’t pack to save her life, is was what I heard, earlier. [laughter]

CE: She can do it okay, but I can get more things in a smaller space, and I can get them there safely.

That’s pretty important for ceramics. Okay, you have to switch now, and send Kate in.

CE: I will.

Don’t tell her what we talked about.

CE: I won’t. It’s your turn, Kate. Are you here?

(Break)

I wanted a chance to separate you and ask about your strengths and weaknesses.

KW: Oh, in terms of being an artist, like your work?

It could be—

KW: Your work, then. Strengths, sheesh, I’m going to have to think about that. I mean, they might be the same thing. One strength I think of is being interested in people, interested in the world, what’s going on.

Curiosity?

KW: I could frame it differently. Questioning? Questioning and curiosity. Weaknesses? Maybe that I feel pulled in many directions. Other times I feel that it doesn’t matter, that innate way I think and work and feeling pulled in many directions. I’ve reconciled with that. I grapple with it, and sometimes I reconcile.

How do you reconcile?

How do you reconcile?

KW: I reason: that’s where my ideas come from, if I allow myself to jump around—

It propels you forward?

KW: Yeah. Yeah.

How about weaknesses just as a person?

KW: It’s similar, as a person, I feel easily influenced; I can get drawn into something, then think, “Is this what I really want?” or am I being influenced by this close friend or this other person?

Questioning your own motivation?

KW: It’s also a strength. You can get to some interesting places if you don’t quite know where you’re going. [laughter]

I needed to hear that. What might you say some of Caroline’s strengths and weaknesses are?

KW: I think she’s got an incredible optimism for work, for life, energy, enthusiasm, drive. Weaknesses, I’d say sometimes she maybe takes on more than—I’m thinking of the garden, actually. It’s a bit of a metaphor. She does get it done, what she wants to get done, in terms of her studio stuff, and balancing the demands of a full‑time job.

That’s funny, that came up earlier in my conversation with Caroline. What’s next for you Kate?

KW: I’ve got a performance project that’s been given some funding and involves singing in disastrous locations. Superfund toxic sites in the Northwest. It’s a Boise State School of the Arts grant.

Congratulations!

KW: Thank you. I still need more funding because I want to pay the performers. I’ve got a couple small video projects I’m working on and more paintings I’d like to do.

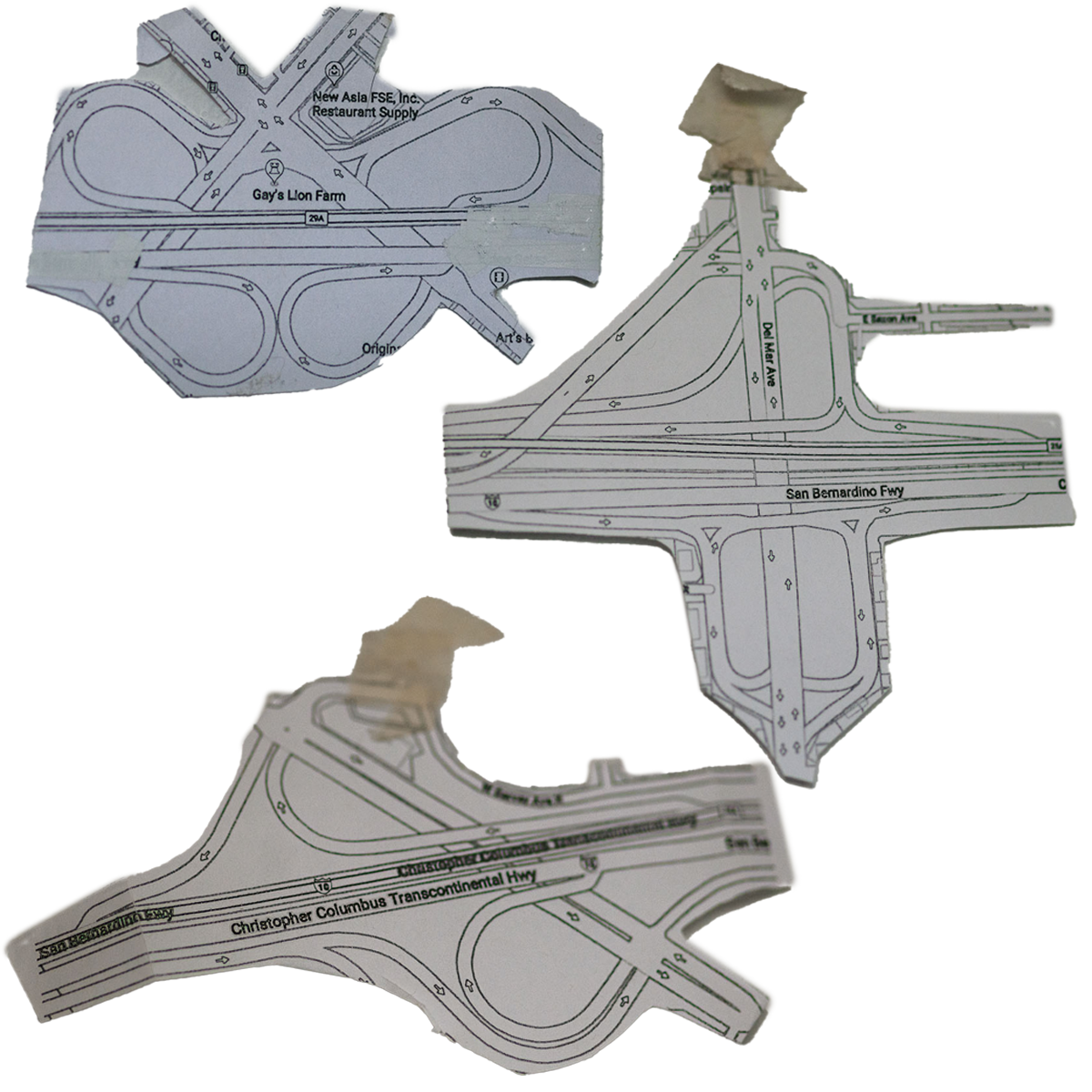

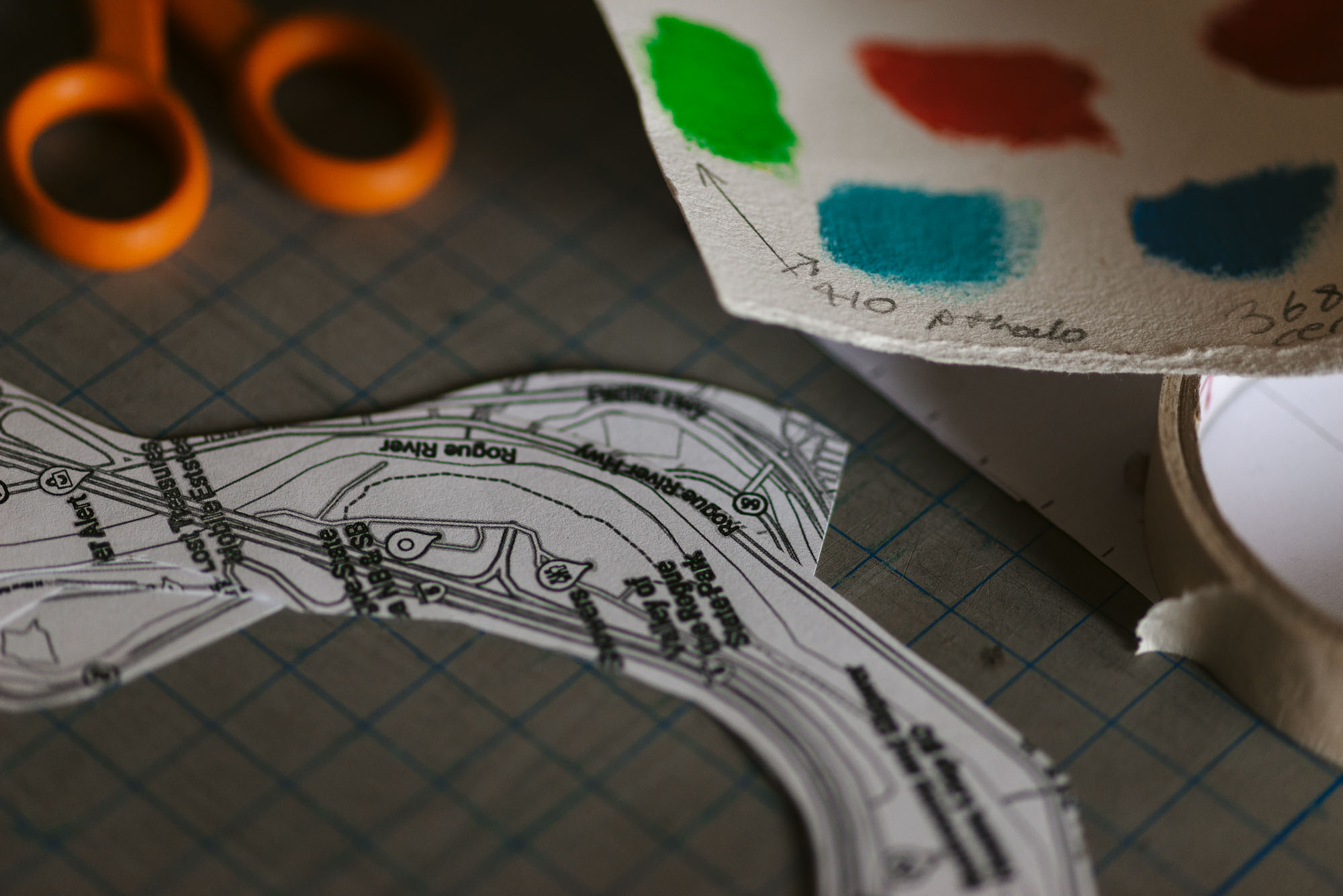

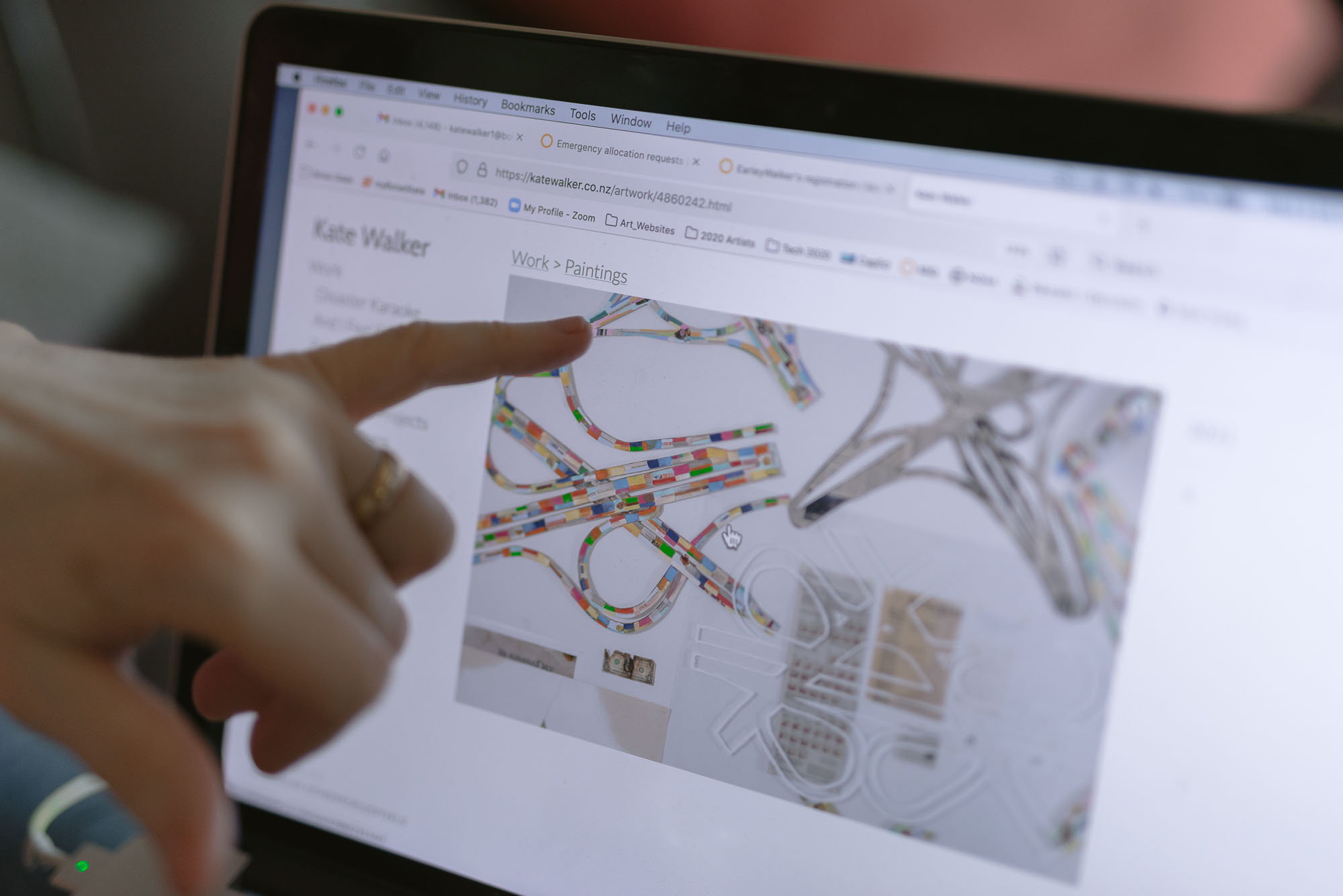

The paintings with the freeway on‑ and off‑ramps?

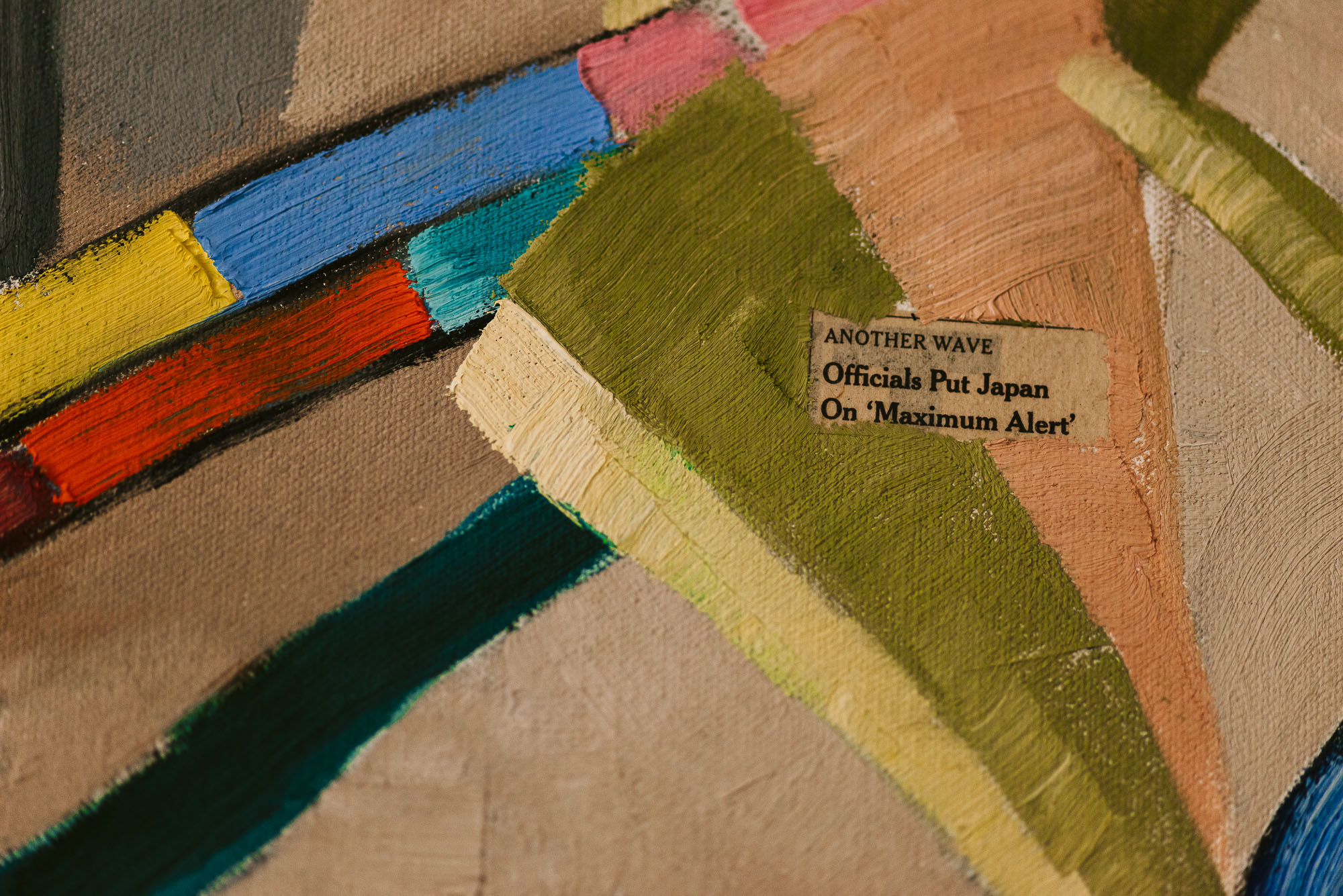

KW: Right. I’m combining them with these disaster landscapes, or some sort of left-over devastation, a specific place after an event has occurred. The highway paintings were referencing land use, environmental concerns or impacts of land use and technology.

And now you are combining that with aftermath. And here’s Caroline!

CE: I’m back.

Caroline, you skipped a question. I asked about Kate’s strengths and weaknesses, but you only listed a strength.

CE: I didn’t list a weakness for Kate?

Did you?

CE: I’m supposed to list a weakness for Kate. Oh, God, it’s hard.

You have to, because she had one for you.

CE: Yeah, but I’ve got more [weaknesses.] I don’t know.

KW: You can think of a weakness for me.

CE: You can’t pack?

I gave you that one, that’s too easy.

I gave you that one, that’s too easy.

KW: Um, I thought of one for you.

CE: I’m easy, though. Okay, I’ve got something. I don’t think it’s specific to you, and it may not just be women, but it’s like, you have successes, but then discount your own—

KW: Oh, confidence.

CE: Confidence, yeah. Confidence that what you’ve achieved is really yours.

KW: Imposter syndrome.

CE: Yeah.

KW: It’s true, I do have that quite a lot.

CE: She does, yeah.

KW: I was going to do a project about resigning from the art world, I thought, I’m going to do that: resign from the art world—unless this application gets accepted. [Laughter] I can’t resign from the art world.

CE: I think we all go through that.

All the time. What was the result?

KW: I was going to resign from the art world unless my video had been accepted into this museum.

Did they accept it?

KW: They did. They did.

CE: Then were we just making empty threats about resigning from the art world?

KW: It was sort of playful. I mean, I probably would not have resigned from the art world, but it reflects a love‑hate relationship. I mean, it’s a natural thing. We have things we love that we also fight with.

Yes, I’m familiar.

KW: Caroline, you had imposter syndrome, too.

CE: Absolutely.

KW: Less now so that you won all those prizes. [Laughter]

A lot of good things coming up, all well deserved.

CE: But we don’t take for granted any of the things that have been given to us. Both of us employed as tenured professors at Boise State is like winning the lottery. That could easily have been someone else, there are a lot of talented people who could have gotten those jobs or been the right person at the right time. None of it was expected and a lot of it was hoped for.

You are both very talented.

CE: It was worked for and hoped for.

North End

September 22, 2021

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.