Creators, Makers, & Doers: Vinnie Bagwell

Posted on 9/21/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History Photography by Dorinda Angelucci and used with permission.

Vinnie Bagwell is a figurative sculptor living and working in Yonkers, New York. She is the creator of the newly installed bronze resin works at the Erma Hayman House in Boise’s historic River Street Neighborhood. We spoke with Vinnie about how she came to work in bronze and her uncanny talent for naturalistic representation, a chance discovery made after she’d stopped painting. She shares with us her approach to public art as a business and her surprising way to find grants (and how she did it before the internet!). Most importantly, Vinnie speaks with passion about the gaps in representation for BIPOC figures in our history: Ella Fitzgerald, Marvin Gaye, and Reverend James Lawson (possibly the most significant architect of the Civil Rights movement you’ve never heard of). Her advice to other artists, “Remember what you love . . . Art has the ability to open minds.”

How did you go from a career in journalism to a career in the fine arts?

How did you go from a career in journalism to a career in the fine arts?

Sometimes, you’re trying to find your way in your 20s, right out of college. I was trying to figure out how to apply what I had learned, in the real world, so I started off working as a graphic designer. I discovered that a lot of people don’t really know how to write. (I had had a mentor in high school, who recommended I take extra English classes to strengthen my writing ability.) By the time I got out of college, I was a writing athlete.

I started off writing text for brochures and magazines, because in graphic design, you have to have the text first. Ultimately, I was invited to write for Gannett Suburban Newspapers for their Herald Statesman newspaper for Yonkers, New York. That was a very good exercise because I had to–kind of like being in school–I had a deadline every week. Later, I wrote for other newspapers and magazines.

When I discovered that there’s grant money for just about everything in the world, that is when I really started fine‑tuning my writing skills. This is called “persuasive writing”. There’s “communicative writing” and then there’s persuasive writing: writing to inform versus writing to close.

Close a deal. A writing athlete?

It’s like being a couch potato versus someone who lives at the gym. If you don’t keep up a skill, you lose it, you forget. By the time you’re in your middle years, you can’t remember where a comma goes, you know.

It’s a muscle.

It’s a muscle.

The brain is like a muscle: The idea is to do something often, become stronger. It’s a great part of what I do. My practice requires a lot of writing.

How did you become a sculptor?

I’m a painter, and I had a painting block. I didn’t paint for seven years. Then, another six years went by. I was trying to find a way to “prime the well.” (When I was growing up, my grandmother lived on a farm. She poured water down the pump to the well, before pumping it for water–particularly if she hadn’t pumped it recently–because it helps the water to flow out. Same thing with your mind.)

You try to do things just to make your mind start turning, then creativity kicks in. I was going to get into pottery, but I ended up trying sculpting, and it was like magic. Such a tremendous love and passion. It was like, “Oh, my God, look what I made.” I had to do it.

It was quite the discovery.

Sculpting is not a good “hobby” if you’re not rich, because it’s expensive to make molds and cast. The big question is where was the money coming from?

Where is the money to do what I love?

I needed to double my income. Do you ever think about doubling your income, like right now?! My artwork was time‑sensitive, then, because I was working in clay, and things were starting to fall apart—it was like “I need money NOW!”

To fire them?

To fire, cast, or whatever. I didn’t know what I was doing. I’m untutored. In order to get people to help me, I had to come up with money. I discovered grants. I was living in the library, trying to figure this thing out: How do you even get a public art commission without the internet?

This is back in the card-catalog days.

The mid‑’90s, we didn’t even have email, yet. We take it for granted, now. In the library, I discovered The Big Red Book and The Big Blue Book, which is now the Foundation Center online.

The Foundation Center online is the repository for all of the grants in this country, on every subject in the world. I had to come up with good keywords. For instance, I’m a woman, I’m a Black woman, I’m a woman over 50, I’m an artist. When you go into the Foundation’s search engine, you can find a grant for anything.

I love how strategic that is. You are reverse engineering your approach to grants. Instead of looking at which grants are out there, you’re looking at what you have to offer and then seeking to discover who is searching for you.

The most important thing about grant writing is to follow the instructions. First of all, make sure you’re eligible. If you don’t have the credentials: “If it don’t fit, don’t force it.” The next question is: What are the requirements, what are they asking for? Just like anybody else, I waded in, and started writing. I started winning early on, which was affirmative.

That’s encouraging.

Exactly! I learned every city gets money from the Federal Government. Yonkers, where I live, has a high poverty rate, 12 percent. That means we get a lot of money from HUD (the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development).

Another question is: what are you trying to do? I want to make art. Well, I asked myself: why should HUD, or the City of Yonkers care? For me, public art isn’t just beautifying; this is me educating. This is me creating an asset for the City, which creates a destination, which is tied to economic development.

You begin to learn how what you want fits in the world, and how it fits into the community. Why it matters. Once you understand that, it’s just a matter of trying to find who supports your work. It’s helpful if you can write because you have to be able to convince them when you’re not in the room. That’s a real art.

What does it mean to be an untutored artist?

It means I’m not going for any formal training. I’m not interested in learning stuff I don’t want to learn. Growing up, going to school, it was like, “Tell me, again, why I have to learn algebra? Why does that matter? How am I going to use that?”

I didn’t want to pay people to teach me things I didn’t want to learn. Going to school for art wasn’t in my mind because I could learn what I wanted to learn out in the world. Or go to the library or Barnes & Noble, and find books. Growing up, I was taught that you can find information in the world. It’s not all in institutions of higher learning.

Describe your work.

I create art for public places. I am a representational-figurative sculptor. That means I do people, and they look like a person.

Realism.

Or as my daughter, who went to art school, would say, my style is grounded in “naturalism”, which is a little different. At any rate, if I’m sculpting you, it looks like you. That in and of itself–to make a portrait that literally looks like who it’s supposed to? Not everybody can do that.

I do candid portraiture. I don’t want you to smile and look at me, and be fake. “Grip and grins”, as photographers say. I want to sculpt you just being you, naturally, doing something. Most of my artworks are, for lack of a better word, action‑oriented.

To sculpt figures naturally, realistically, is a gift.

I learned early on that I had a skill for bas‑relief. I’m a mathematical person, I minored in math, I love math. Bas‑relief is a two‑dimensional sculpture that gives the illusion of three‑dimensional space. There’s a lot of math that goes into it, to discern the background, middle ground, foreground.

To establish an accurate illusion of perspective.

Let’s just say, I have a picture of you, sitting in a chair. There’s the wall behind you. The chair is between you and the wall. Then, there’s you. I have to figure out how to convey that depth of field within an artwork that’s only two inches deep.

When I started competing for public art commissions, I used bronze resin because it allowed me to make a sculpture, and afford casting to show commissioners what I wanted to make. I started off making bas-relief wall hangings. Then, I began using narrative bas‑relief on the surface of my three-dimensional sculptures to expand my storytelling ability.

Bas-relief is on a picture plane that we ‘read’ left to right versus sculpture in the round that we interpret as an object.

For instance, my commission of Frederick Douglass at Hofstra University sits in the middle of an open plaza. People may approach him from every angle, so I wanted there to be something on the back. That was the first time that I tried using relief sculpture on the surface of a sculpture. I liked it. I thought, “Oh, that works, that’s cool.” After that, I decided, “I’m going to make this my style.” I’ve found it’s a really good way to tell stories, people respond to it, and not many artists employ this technique.

As a child what was your relationship to creativity and the arts?

I think many artists are just “born”. Some people “become” later, when they go to school or become exposed to different creative experiences; but some of us come here already–I’ll just say–full‑blown artists. We’re born this way!

I learned how to read the Christmas I was in kindergarten. The second semester in kindergarten, I learned how to write. I learned stuff at home, with my mother. By first grade I’m working on my script, while my teacher is trying to teach the other children how to make an A. I’m making a capital A with a flourish, you know. (I was in a visually handicapped class because I’m legally blind without correction.)

I had no idea.

My first‑grade teacher was blind, and had her sight restored by the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary in New York City. She said to my mother “If your husband has good health insurance, please take her there.” My mother was for anything that was going to make me see better. Thus, for eight years, I went to the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary to get the vision I have.

Your mother wanted something better for you.

My mother’s vision is not correctable, she does not have central vision: Put your hand in front of your face, imagine there’s nothing but a blur in the middle, you just have peripheral vision around that fog. That’s my mother’s vision.

I’m myopic: I don’t see far away. My contact-lense prescription is -9 1/2, minus -10. Minus-10 is about the strongest contact-lens prescription there is. If my eyes were any worse, contact lenses would not help me. I was one of the first children to wear hard contact lenses, only because they were offered to help my therapy at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary.

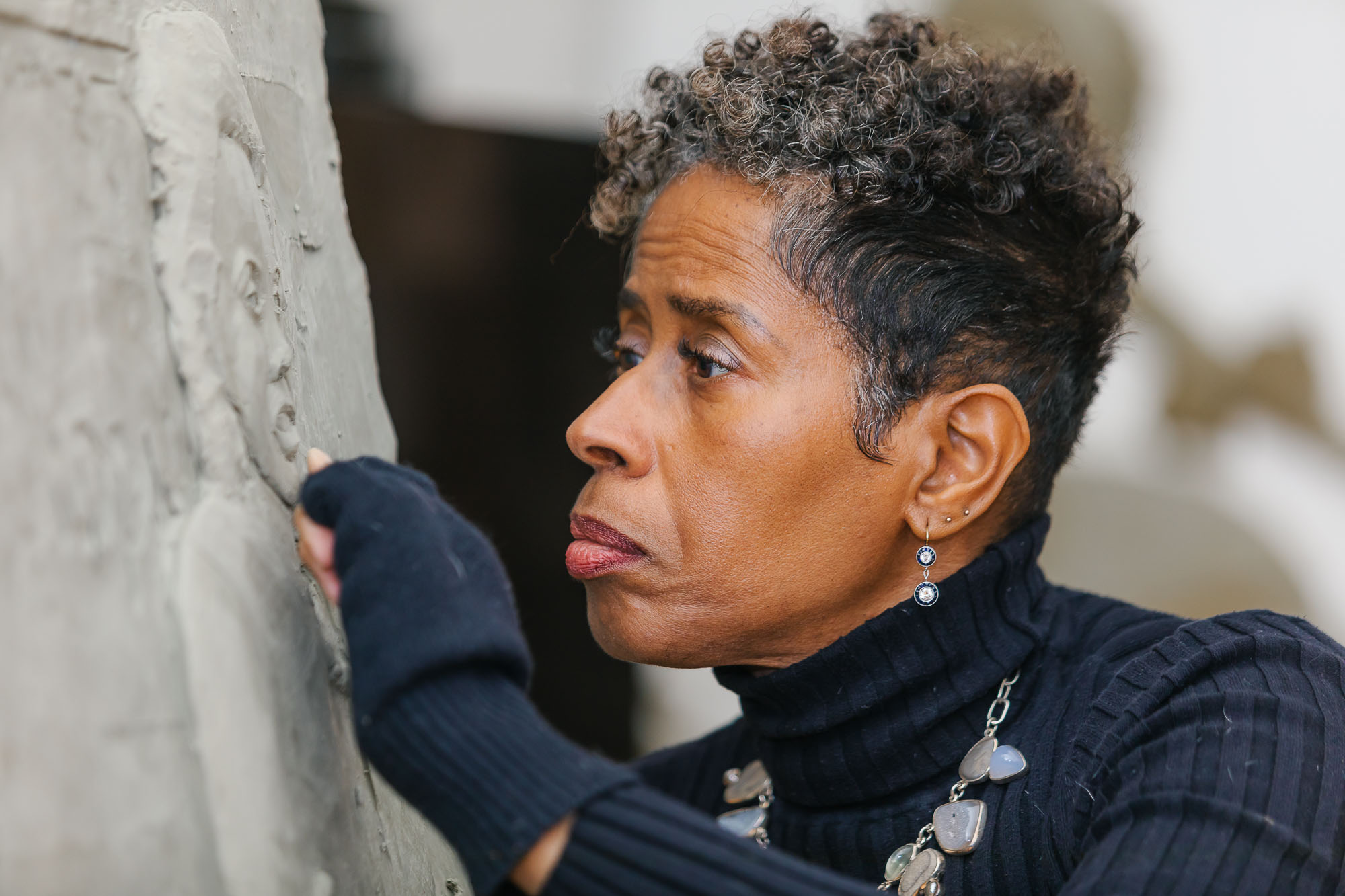

This explains the photos I’ve seen of you working so closely to the clay.

Most of the time my nose is almost on it because, again, I see better close up, and I’m focusing.

What do you find beautiful in life?

Everything. I didn’t know that I loved everything until I discovered Pinterest. I have like 110 boards. I love rocks, I love tree bark, I love keys, I love tree houses, I love stones.

People are fascinating. I’ve always been fascinated by people’s faces. I think that’s why I started off drawing people’s faces. I didn’t really care about history, growing up. I realize, in retrospect, it was because my history teachers were boring; they weren’t good storytellers.

[laughing]

History is really fascinating if you tell the story well. It’s amusing to me that history is now my life.

Your work references history, true stories. What’s your opinion about the purpose of public art?

There are different kinds of art in public places. So, I’m only talking about public art that’s about history, not about art for beautification, or interactive. I’m talking specifically about art made to talk about the memory of people.

The first thing I realized was that I didn’t see public art about people of color. Not just Black people, but anybody not white. That made me feel like there’s room for me.

I looked at my town, Yonkers, New York. The thing Yonkers likes to tout the loudest and the longest is that Ella grew up here, so did Mary J Blige, so did rapper DMX, so did W.C. Handy, “The Father of the Blues”, but when I think of the most memorable person from Yonkers, it’s Ella, hands down. She transcends–oh, my goodness–she transcends everything: race, age, ethnicity. She’s an internationally renown icon. I thought, “She should have a sculpture. Why don’t we have a sculpture of Ella, if we love her so much?” So I wrote a proposal.

It seems obvious, doesn’t it?

It did. Again, this is ’94, we didn’t have the internet. I couldn’t Google anything. The City of Yonkers only gave me a fraction of the money. The foundry is the one who made it happen.

They worked with you, even without enough capital?

The foundry cast Ella at their cost, no mark-up. It was an investment in their business. Like, “This chick–she’s on fire, let’s give her the first one, and we’ll get paid on the second and thereafter.” For me, it was a major hand because you can’t get into public art just by going to school, getting a degree, saying, “Hi, I’m going to do public art.” It’s not that easy. It’s just not.

The foundry could see the long-term benefit of working with you.

The foundry could see the long-term benefit of working with you.

It was an investment. I used to go in there, and cry and carry on because I love the medium so much. It was unnerving to not know what to do. I was going to the foundry to get educated, like a seven‑year‑old who wants to ask 27 questions before you’ve had your coffee.

However, they understood that I really love the work. I asked them, “Why are you helping me?” And they said, “Because we’re artists, too.”

Yes, absolutely.

I’m telling you, there’s nothing more important than when somebody believes in you. It’s nice when your parents believe in you, when your friends and your family believe in you; but when strangers you don’t even know stand up in the middle of a public forum to support you because they believe in your vision, it’s a great accomplishment.

Yes, which did happen to you, but that’s a different story. [laughter]

When I came to Boise, the big question was: why Erma Hayman? Who is she, and why does she matter? Back when I was first starting to sculpt, people asked, “Oh, are you only going to do artwork about Black people?” I said, “Well, I’ll do art about white people if you want me to, but Black people are the ones who aren’t represented.”

I’m Black, so that makes it easy for me because I understand. I did Teddy Roosevelt, but, again, a lot of people have done Teddy Roosevelt. He’s not wanting.

Very true. I feel like you’re filling in gaps.

Yeah, big gaps.

How does civil rights in our current moment inform you as an artist?

Oh, my goodness. I just won a commission from Penn State University for James Lawson, Reverend James Lawson. Do you know who he is?

I don’t.

Most people don’t. He is the architect of the Civil Rights Movement, not Martin Luther King, Jr. James Lawson directed Martin Luther King on what to do. He was the one who studied under Gandhi. King said, “You have to come home, we have children who need you. They need you to mentor them; you’ve got to help.”

This man stopped whatever he was doing with Gandhi, for real, and came back to the States, to Tennessee, to mentor eight—they call them “The Children”, but they were college students, they were brand new.

They were emerging.

Guess who they turned out to be? John Lewis, Diane Nash, Marion Barry, a whole crew, eight of them. These people grew up to be heroes, leaders, movers and shakers in the Civil Rights Movement. James Lawson designed the March on Washington, the March on Selma, the Freedom Rides, the Sanitation Protest March. This is the guy who said “I Am a Man” to sanitation workers and they made it their motto.

Rev. Lawson said, “Racism is grounded in the idea that a man is not a man, I am a man!” You’ve probably seen a picture of him, but you never knew his name. That’s how marginalized Black people are. The guy created the whole civil-rights war-general, instructions, and nobody knows his name! He’s still alive, for crying out loud! That’s the most exciting thing. He’s 92. I can ask him anything about that time, and he can tell me firsthand. That just–it blows me away. I love it.

Wonderful! At Penn State? What’s the scale going to be?

Penn State Fayette. Life‑size. It will go in their library.

Congratulations.

He’s getting his turn. Finally. And he’s living to see his turn.

That’s a big deal.

It’s all a big deal. I did Marvin Gaye for the District of Columbia. They finally decided to create a recreation center where he grew up in DC and name it after him. When they asked about the budget, they wanted to know what the pedestal was going to look like, I said, “What pedestal?”

[Laughing.]

I said “You didn’t make a budget big enough for a pedestal. But I’ll tell you what, I’m going to throw in a pedestal because, frankly, I can use the tax write‑off. Marvin Gaye is the prince of soul. He deserves a serious pedestal”, and I gave him one. There are so many stories that deserve to be told. Human-interest stories about triumph of the Spirit. They could be inspiring to anyone, you don’t have to be Black to be inspired by the tenacity, creativity, ingenuity of these people. Anyone going through an oppressive trial can rise above to triumph, and that’s what these stories bring.

What’s your approach to the Erma Hayman House project?

Erma Hayman’s commission was challenging in the length of the wall: It’s very long. What can I do that will have an impact? I chose to go a little bit outside of my own box and create a montage of memories that might belong to her. There’s a story of hers about how a teacher said [Erma’s] daughter couldn’t be a ballerina. The images in the work are prompts or bows to certain stories. If you know the story, then you know what it means. It’s a memoir.

I don’t know the story.

Erma Hayman had a little girl in school, the children were asked to talk about what they wanted to be when they grow up. She said she wanted to be a ballerina. The teacher told her she couldn’t be a ballerina (because she was Black), so she came home crying.

Erma–this woman didn’t have a car–she walked to the school, which took quite some time, looked for the teacher, snatched her up, and said, “Why can’t my daughter be a ballerina?” and by the time she finished grilling her, whatever she said–because, you know, they don’t really tell you all the details–when Erma left, her daughter was allowed to be a ballerina.

It’s the idea: You shouldn’t dampen children’s ambitions. The biggest thing I appreciate about Erma is that she was an everyday woman and a philanthropic kind of person. If she found out you needed diapers, she’s going to bring you diapers. She baked. She made contributions and shared herself with her community, she was known for that. I grew up with women like her, oftentimes, you learn this kind of service in church.

I was thinking the same thing.

In the old days, people went to church and they learned that you’re here to be of service. People find their own way, this is the beautiful thing about Erma. Another good story akin to hers would be Walter “Doc” Hurley in Hartford, Connecticut.

Again, an everyday man, a regular guy, comes back from the army, wants to teach basketball at the school, and they won’t let him because he’s Black. He decides to teach basketball at the boys club, and discovers that most of the boys he is servicing are impoverished. He raised money for them; and at the end of his life, this man sent more than 500 kids to college on scholarships. Erma’s the same way, looking around her community, seeing what needs to be done, and doing what she can.

It really is that simple.

That’s a formula: Look around your community, see what you want to see; and if you don’t see it, create it. What’s missing? What do you think your community needs? You can do it. You might even find people with like minds and work together. Sometimes, you can do it by going to your city government–because the government serves you, not the other way around–and say “how can we get this done?”

Big or small.

Erma Hayman made it to a hundred-years old. How do you do that? Eating well, exercising, staying busy in your community. She had three children, and took the time to educate other children too.

Erma Hayman was a tea drinker. That might seem like a simple thing, but, you know, some people get a lot of inspiration while they’re drinking tea, chilling. Taking time out for self‑care.

The Hayman’s house is the last standing tribute to a neighborhood. That in itself is a major thing. As an artist, I try to give people a reason to come; I created a destination to help people learn about this particular neighborhood in Boise. A lot of places are gentrifying, nationwide, and you have to remind the new people coming in that it didn’t always look like this, that what was here, before, matters. It is the foundation upon which your community is built. Don’t forget history.

Very well said. What kind of advice would you give to people just starting out in a career in public art?

Remember what you love. People can tell what you’re focusing on and where you’re putting your energy. Learn about art as a business. We’re makers of things, but if you’re going to be self‑employed you have to learn about accounting, branding, and marketing. Learn to articulate your ideas, to write, and speak well. That’s the basic foundation. You don’t have to go to school, but it’s helpful to find people who are already doing what you want to do, and ask questions.

Mentors.

People who can give you insight. A lot of things are virtual now, so you don’t even have to go anywhere; you can do it from the comfort of your home.

You said “remember what you love”?

For me, it’s important to do things that matter. At the end of the day, why should anybody care? You have to find out what matters to you, that’s first. You may not want to do public art about history. Maybe the history is not your thing, well what is your thing?

There is so much you can champion. I have to figure out the most important thing for me to say, today. What should I be giving my attention, my time, my energy to, today? What’s going to make a difference? It’s not all about me. When I discovered sculpting, it occurred to me that maybe God wanted me to share the gifts.

For people of color–Black people, Hispanic people, Asian people, anybody who is not white–this is a remarkable time because the art world is embracing diversity in a huge way. If you’re going to try to get into public art, now is the time. All of the sudden there’s room for new people. The challenge is coming up with brilliant ideas and learning how to execute them. Once you come up with the idea, there are people who will hold your hand, but you have to come up with worthy ideas.

Something of value?

Something that will have lasting value; when you put a bronze in the ground, it’s going to last a couple-hundred years. Your work is going to be speaking for you, for a while, so you have to be sure your message is clear and that it will continue to be relevant.

That’s a great goal.

If you’ve made art long enough, your eye has sharpened, you’re more critical; but the amazing thing is when you can look back at old work and say “That was my best.” At that time, given the circumstance, that’s a good piece right there; it’s still strong.

And not just in art. Give yourself the benefit of saying, “I did my best with the time, context, and resources I had.” That’s a gift to yourself.

That’s how I recommend people [approach] their work. Do the best you can, and when you look back, given all the extraneous barriers, be proud.

You had success early on, but what about someone struggling to gain affirmation?

You can also create your own commissions. I’m an outside-of-the-lines kind of person. I believe in breaking rules. So if you tell me a rule, I will look for the loophole; to figure out how to widen it.

It occurred to me, “If I can’t figure out how to compete, why not create my own?” If you can’t find an opportunity that fits your matrix, create your own matrix. Create your own opportunities. How you do that depends on your vision; how well you can see into the future.

If you could sit down to dinner with anyone from the past or present, who would you choose?

We were laughing about this question the other night, I said one of my dogs. [laughter]

Okay, you are allowed a person and a dog.

Actually—all of my dogs.

How many dogs are we talking?

Seven. I was one of those children that needed a dog. Honestly, I still need a dog.

Okay, seven dogs and one person, who is it going to be?

I find myself wanting my grandmother; she tried to tell me things when I was younger, and I–you know how when you’re in your teens, you think you know so much–I argued with her. [laughter] She would get a little smug with me, like, “Mm‑hmm, okay.” You know, “Okay, you’ll see.”

Of course, now I understand, I’ve been through trial and error. Something I learned through her is the right approach to talk to young people is important. They think they know so much, and a lot of times older people, who do know so much, aren’t able to convey it. There’s a barrier.

They’re not meeting.

It’s made me very conscientious when talking to young people, to not sound so authoritative, pompous. To just say “Let me tell you something, not because I’m intent on being right, but because it will make your life easier.”

Your grandmother left an impression on you.

I would tell her “I’m sorry.” Well, “I’m sorry. You were kind of right, sort of.” [laughter] Anybody else would be gravy. Sure, I’d like to talk to Jesus. I would like to talk to Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass. As a matter of fact, I want to the talk to Frederick Douglass for a while. They each bring a certain illumination, an understanding about reality. As you age you realize your ability to discern reality shifts based on how open‑minded you are. This is the beauty of art. Art has the ability to open minds gently and cause change.

Downtown Boise

October 5, 2022

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed.