Creators, Makers, & Doers: Maria Michurina

Posted on 4/4/23 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Maria Michurina, Artist-in-Residence at the James Castle House, immigrated from Russia with her husband, Pavel, to the United States in 2010, the first of multiple pilgrimages. But first, there is a war between Russia and Ukraine; something she says is difficult to comprehend and impossible to avoid thinking about. Although physically removed, for Maria, the effects are wide: relationships, energy, actions. And there is a weight, a question, “Will things ever be normal again?” Despite this, she speaks with an abundance of joy, the kind found in someone doing the thing they are meant to do. Daughter of two physicists, she studied mathematics, not art. (But you’ve GOT to hear about her offer from the New York Studio School!) So how did she come to work as an artist and share with us her understanding of composition, theory versus practice, and the idea of failure? She couldn’t resist.

I understand you had some obstacles getting here?

I understand you had some obstacles getting here?

In 2019, I saw James Castle’s drawings in Seattle. I came home very excited, looked at a map, and realized [Castle’s home in Boise] is an eight‑hour drive, so I was here in eight hours—that was the first time.

You made a pilgrimage!

Kristen (the City of Boise’s Cultural Sites Manager) showed me the apartment, the studio. I wanted to apply [for a residency], but didn’t, and then the pandemic began.

And the residencies stopped for a while.

When applications opened again, the war began, and I didn’t feel like doing anything. My family’s still there. I moved with my husband in 2010. We moved to Canada first, to wait for visas because we were already packed and prepared; we wanted adventures [chuckles].

How has the war affected you?

It’s hard on many levels. It’s very hard to comprehend what is happening. Very few families have members on only one side. The fact that these two countries are fighting with each other is very strange, irrational, and unbelievable, even now, after a year.

Has it been a year?

It’s been over a year. It started February 24th.

It seems like yesterday.

No, it doesn’t feel like yesterday. It feels like a whole life passed through. The second part, which is very hard to comprehend, is how strongly people are fooled by propaganda. In my family, we are not fighting, but we definitely see, like, who watches TV and who doesn’t. A couple days ago, I talked with my stepmother and she knows I have a different point of view. A year ago, it was really hard to talk with each other. She told me, now, people cannot break their relationships because of politics. We should still stay as families, very close, and I agreed. But sometimes it’s really hard to keep up the conversation when you can only talk about flowers.

Has the war changed your art practice?

Has the war changed your art practice?

It changed the mood of it. Sometimes I feel like I could not work, it’s very hard to get started. I came up with a method for how to get out of the hole. Sometimes I feel that all my life is getting out of a hole, which is fine.

How did you keep going in the studio?

My method is keeping some things to work on every day. They should be small, you should have a few, so if you don’t feel like making one, you switch to another, without thinking of the process, the result, anything. I had two things I was working on. I finished the one on the right before the war. And then I was in the hole again. To get out, I recreated collages from memory. At the end of the week, I would sit down and think about what I remember from the week and collage it. Very small.

Like a diary?

And the subject of the diary was changing. It shifted to the war, then I guess it shifted back because I felt like I need to leave somehow.

Was it a choice?

No, it was not a choice. It’s self‑protection. If you walk on the street—someone, I don’t know, knocks you, you jump because it’s your instinct.

Reflex?

Yeah, reflex. You can’t live forever in that state. A year is a pretty long time. When the war began, I didn’t sleep. It was far away, but you go outside, hear a helicopter; you want to hide. It’s not logical, but that’s what is happening. You understand reality differently.

It’s heartbreaking. To imagine the kind of—the violence.

When I talk with my family who stayed in Moscow, which is probably the safest place for now, I feel that they are totally broken. Even though they are not in the middle of the madness. Even without physical harm, people get really broken. I don’t know if there is a way out. I don’t know if it will ever be back to some sort of normal.

Thank you for sharing that.

Thank you for asking.

I don’t know where—where to go from there?

I guess anywhere.

Your training is not in the arts?

I studied math. My parents worked as physicists. I didn’t do well with physics; math was more comprehendible. I wasn’t good at school so when I went to the university it was a big surprise.

It got harder?

Yes. But I made it through. The first year was harsh, I was failing, literally, everything. Then my mom passed away; I didn’t study well, it was an emotional challenge, so I had to take a break for almost a year. After that it became easy, somehow. I was getting good grades, and it was easier to keep up in lectures. I’m not sure why. Maybe it was not the right time, maybe I was too stressed out, but anyway. I worked at the Institute of Mechanics as a junior researcher. It’s a part of Moscow State University. I worked on mathematical models of inner eye pressure, things like that. But that’s not paid. In Russia, science is not paid, so I had to figure out how to get paid.

What do you mean?

What do you mean?

Well, you get a salary, 200 dollars a month, and prices are like in New York, so…

It’s a very low‑paying job?

Very low. So you have to be happily married or something else. [Laughing.]

Which surprises me because the kind of job you’re describing sounds very specialized requiring higher education; I would imagine it would pay well here.

That is true. That’s why many people who want to stay in science move on.

Out of Russia?

Yeah.

Is that why you moved?

Is that why you moved?

No. But probably it was similar reasoning for my husband. It was his decision. We were not married yet, we worked one subway station away from each other. One day, we met for lunch and he asked me if I wanted to marry him and if I wanted to move with him to the US. I guess it was written on my face when I came back to the office; everyone asked me what happened. I was like, well, “Two offers.” And everyone said, “Say yes to the US, and no to marriage.” [Laughter]

What did you say?

He told me where he wanted to move, and at the time I admired an artist who published a book, this book was translated to Russian and I just fell in love. Her name was Joan Colvin. She was a quilter; I’d started quilting. She lived on this island, and people come to study with her. I thought it was like a dream.

Which island?

San Juan Island in Washington. And when Pavel said, “It’s somewhere in Redmond, where I’m offered the job,” I looked at the map, and I saw where it was, and, “Yes, sure, I want to move.”

Did you get to meet her?

Did you get to meet her?

I couldn’t find out anything about Joan Colvin for a few years after we moved, then I realized she’d passed away four years before. There’s a quilt museum in La Conner—I was showing there, and when I entered the museum, behind the cashier stand was her quilt. It was Madrone Tree which I admired.

How did you go from an education in math to working as an artist?

I don’t know, but here is the story. I didn’t do any art.

Nothing?

Nothing. I had a horrible job which I quit in 2008.

In Moscow.

In Moscow.

For some time, I was just staying home and doing all sorts of things. I started quilting, and I liked the geometry. I’ve never tried to make a picture out of fabric. I kept doing it. Then we moved here. Here, quilts are more popular, more developed. I went to a quilters club near our place; it was quite interesting experience. I couldn’t say anything. They were making fun of me so much, but it was a good exchange.

Did they make fun of you because you were new?

They thought I was cute. I was much younger than everyone. They were so sweet; it’s like a hundred people. They had once‑a‑week meetings in the basement of a church, which I thought was creepy [laughter].

You were a new face, speaking English as a second language.

You were a new face, speaking English as a second language.

Like 50 years younger [laughing]. It was fun. I entered another quilting group in Seattle; they were serious about shows, most had an art education. My brother is an architect, a painter too. He said if you want to make pictorial quilts, you want to draw. You should take some classes, drawing, color; to learn—

Formal technique?

Approach, yeah. I went to Bellevue College and took all the classes they had. Some classes I took five times.

Did you get a degree?

I was thinking about a degree, and I even flew to Russia and got a translation of my transcript, brought it here, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. Then I couldn’t figure out how to pay for it.

Oh, yes, there is that.

Oh, yes, there is that.

And I have master’s, so for me—

In mathematics?

Yes, so for me it would be harder to get a scholarship. I couldn’t figure out all the details. In 2019, I went to the New York Studio School for their short mentor programs. Graham Nickson, the dean, asked, “Why don’t you stay?” I wanted to, badly. I told him I have a family, I have a job, it’s a big change to move to New York, I’m not sure I could stay for two years. He said, “Okay, we’ll pay for this year, then you can go back home for a year and come back for another year.”

That’s an incredible offer!

I called my husband; we had a hard time between us at the time. I thought, well, we got married because of many things, and we have a really strong connection. We would have to work through it first; we stay together, we separate, it doesn’t matter, but we have to figure it out. And then I can make a choice about the school.

One thing comes before the other?

One thing comes before the other?

I didn’t think about the school for some time, then the pandemic began. I just worked on my own, and I got so happy—I didn’t go to the school. I didn’t see a way to do the degree, because I think it would not let me do what I want.

What do you want?

I want to be honest with myself. It’s hard to do in the school. You have no time for that. You’re constantly told what to do. When people tell you what’s wrong with your work, you have to, first of all, rely on yourself no matter what they say. You may listen, but, sort of listen. This kind of way. I was not strong enough to go to the school when it was all happening. And now when I’m strong enough, I don’t want to go to the school.

I love hearing that. You want to be honest with yourself. How does that come out in the work?

For me, it starts from very simple questions, questions I didn’t ask myself for many years. More than that, I was not able to answer basic questions, “Do I like the shape?” “Do I like the color?” that’s it. That’s where this all started. If you honestly can answer these questions, then the rest will go smoothly. In the schools, I felt like I needed—I needed to make it right, but there is no right. The only right: you want to like it, that’s it.

“Right” is inside you?

“Right” is inside you?

Exactly. No one can tell you. And you cannot explain your right, you can’t put it in words. You can see it, and you can accept it.

Is it an innate talent a person is born with?

I don’t think it’s talent. It just you look at things—all of us, we look at things, we like them or we don’t like them. They all are composed in some way around us.

There is no such thing as a non‑composition?

Everything is already composed for us.

Some people might say you have to be taught or learn those skills or—

I think people know theories. Theories come after practice. These are all approximations and they are not coming from inside of you. You can come up with your own theory if you want to. You can get excited about people’s vision of the world, but you can’t rely on those theories when you work, because they, in a way, do not make any connection to the world and to your work.

What do you mean not to the world?

The world is something that exists, theory is theory.

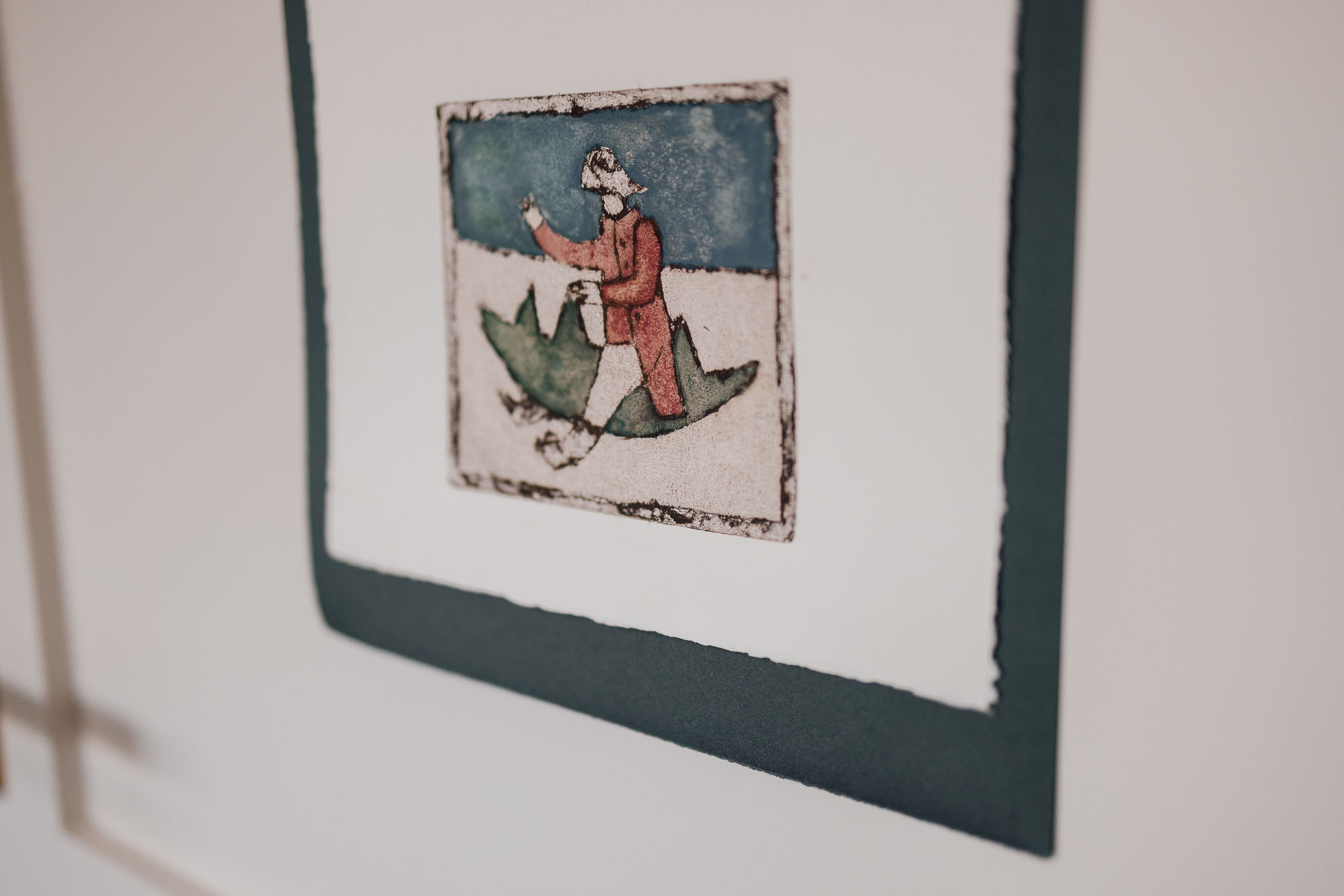

Looking at the work on the walls here, are you beginning with observation?

I like to observe things, to document them and derive from there. But here, I realized I don’t need that starting point. All I need is to sit down, mix the color, which I like, put it on, make a shape, which I like, or maybe not, mix another color, put another shape, and so forth. Eventually, it turns into something I enjoy. It will probably happen even faster than [it would] if I start from this particular tree. Because when I start from a tree, I have a long way to go to depart from the tree. I enjoy the tree, though.

What is it about James Castle’s work that drew you?

He didn’t treat any scrap of paper as something that he might put aside. It’s the only paper he had, he had to make something out of it. If you look at thousands of his works, some papers have a couple of marks, probably he did that in a second or so, but he treats it as a piece. He values it the same way as he would value a more detailed drawing or painting which probably took hours.

Each thing has its own precious value despite the time involved?

Each part, each piece is a valuable part of the whole. If you leave out something, things maybe people would call sketches—[laughter].

Yes, we had this debate earlier. I’m not going to—so it wasn’t a debate, but—okay, sketches. [Laughing.]

If you leave out these sketches, you lose everything. It has to be together. Sometimes I feel like there are two types of artists. One artist can make a masterpiece, you spend weeks looking at it, and if you remove their entire practice, you will still say, “Oh, wow, this is a great piece.”

And there are other artists with whom it works differently; you can’t leave out the practice. You have to look at it as a group. I feel like Castle is this type of artist. I feel like I’m this type of artist.

A sketch. We could call it a step.

A sketch. We could call it a step.

Okay, let’s call it a step.

You are working with a printmaking technique using cardboard plates. Most printmakers think of the plate as a step that is not part of the final work. Looking at the plates hanging behind you, are you treating them differently?

It’s nice to touch them. I like the drawing quality of the ink. I wanted to put this string and hang them as pieces. They are soft, so you can easily make a hole and put a string.

Who is in charge to say these are not finished works?

Who is in charge to say these are not finished works?

Exactly.

Nobody.

I think they are. Everything is. So instead of saying a sketch, I’d rather say a drawing—

But not a sketch, anything but a sketch. What does your brother say now?

I feel like with my brother, we went like this. [gestures]

In two different directions?

Because I departed from the formal. Formal, I feel, doesn’t really work for me well. I had to take off. And as soon as I took off, everything became good. Sometimes when we talk about how we think about painting and what we value, we can’t find common language. One time we talked on the phone, I was so excited, I was telling him about some discoveries, I was talking, talking. And then I could hear snoring. [Laughing.] It was late, late at night.

When it comes to art, you value different things?

When it comes to art, you value different things?

He has an academic background. So, his approach is based on it. Accuracy is important to him. Theories are important to him. This way didn’t work for me, but I love his works with all my heart. For me, whatever you feel like now, you should do it. I guess, for my brother it’s more of a mix of feelings and knowledge.

I’m learning that. There’s very little I can do to create momentum doing something I don’t want to do. I can force myself, and it will drag on slowly.

But, before you start, you don’t know. If you start, you [might] realize, oh, it’s fun. Or, umm, maybe it’s not fun, then do something else. You have to get started.

How do you describe your work?

Collage is a big part of my practice. The way I think about painting, the way I think about prints, it’s all coming from collage. It’s very shape‑oriented.

Define collage, then.

Define collage, then.

Collage is an image made of very distinct clear shapes, which you can change or replace quickly. That’s how I would define collage. I treat painting the same way. With drawing, I put one shape at a time, I look at the whole thing and treat it as a box. So you have a box—

There are a lot of boxes in here.

You take a shape, you put it in a box, and you have a different box at that moment. You find another shape, and you have freedom of putting it in this box in a shape in it, and so you put it there. Now you have a new box. It’s one at a time. I never know what it will be, how many shapes I will put in, how many I will take out.

You’re not thinking in terms of a moving point, as in a line. Most of the work I see as representational, but this group is more abstracted. I do see a horizon line, but they seem to be departing.

You’re not thinking in terms of a moving point, as in a line. Most of the work I see as representational, but this group is more abstracted. I do see a horizon line, but they seem to be departing.

Really? Oh, I felt so at first, then I changed my mind. I went to the [James Castle Collection and Archive], and I looked through a lot of paintings. I got really inspired. I ran back home, and I thought, I just need to put color to some paper right now, and it was not very important what the subject would be. I grabbed my drawing books, and I opened on a random page. And on this page it was, you know, a couple of blocks away from here, there’s a dirt pile. And, “Oh, that works.” I like the combination of this rectangular pile and the pathway which was a rectangle, and some dirt, and some trees nearby. So I just kept painting this pile, and it became one group.

Were you more interested in the color than the shape?

I’m always interested in the shape and the color; they don’t separate.

You said you ran home “I have to put color down, right now!”

In a shape.

In a shape. If you could give yourself some advice, what would you say?

I don’t know. I don’t like to give advice to other people, same for myself.

How about words of encouragement?

Oh, no, come on. [Laughing.]

Words of caution?

Words of caution?

What I keep saying to myself, it’s sort of advice: you know, here I didn’t waste anything that I started, because if it doesn’t work, you can still make something of it. Until you ruin the paper. Like this work I ruined the paper. So then, I cut out the squares, and realized, “Oh, it’s 28, it’s like February,” so I made a calendar.

I see that.

It’s easy to get frustrated because things do not not work out right away. It’s not a failure, it’s moving forward all the time. When you come back to it tomorrow, and really push it through maybe you will feel that you fail again; but the next day, or maybe a month later, you will make it work, this little piece of paper, no matter what. There’s no way to fail. It’s easy to forget that.

This month, I had to say it to myself so many times, with every single mark, because I came here and nothing worked, I couldn’t paint, I couldn’t say if I liked the color or not. I couldn’t—

You couldn’t answer that question for yourself?

But it all works out. You just keep changing it. I still can make it work, any piece, any scrap of paper. Like these paintings, these are prints. Underneath there is a print which didn’t work out. Because I don’t want to waste it.

Do you throw anything away?

You see these scraps under the table, I will make paper out of them.

What are some of your strengths?

Oh, I don’t have any. I have only weaknesses. [Laughter]

Maria stop. You’ve got to come up with something. I’m in a room full of work—please, you’ve got to come up with something.

These are all weaknesses. I can’t resist, I keep painting because I can’t resist.

Seeking honesty in your work, I think that’s a strength.

Okay, that works.

Speaking vulnerably, like you did today, that’s a strength.

Okay.

And I really, really, really, really like your use of line and shape. We didn’t talk about the figures, but some pieces have little animals and figures that are leaping and jumping, which bring me so much joy. They make me really happy.

Me too. That’s why I paint them. I think painting should make people happy, the process. If it doesn’t make you happy, maybe it’s good to switch to something else for a moment and come back to it later.

North End

April 4, 2023

James Castle House Artist-in-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed.