Creators, Makers, and Doers: Brooke Burton | Karl LeClair

Posted on 6/28/17 by Brooke Burton

Karl LeClair began interviewing local artists in 2015 with the goal of promoting the work of Boise’s Arts & History Department. Two years later he sits down with fellow artist Brooke Burton in her basement studio to talk about changes in the department, art funding, and inspiration, and introduce Burton as the new lead for Creators, Makers, and Doers.

BB: Thank you for coming down to my studio and being on the other side of the interview process. I must say, “Congratulations on your new job!”

KLC: Thank you.

BB: Tell me about how you started with Boise’s Arts & History Department.

KLC: Well, let’s see, I started with the department four years ago. I got hired right out of school, so I’d just got my bachelor’s in arts. And at the time the City of Boise was running the Sesqui-Shop which was a really cool space downtown, kind of an interpretive gallery/exhibition space that focused on the marriage of arts and history, all Boise-centric exhibitions.

BB: That shop was awesome.

KLC: Yeah, I really miss it. Started out working as the shop attendant there with Rachel Reichert, our Cultural Sites Manager, who was managing the space. Then they brought me on as program assistant for the department. It was the first time they’d had that position funded in a while and basically everybody was competing to have me help them.

BB: You were in demand?

KLC: Yes. [Laughs] In very high demand. I was working on research projects for Terri Schorzman, the director, and helping Josh Olson, the assets manager, with maintenance and conservation. He never had anybody helping him; we were going out and waxing bronze sculptures and researching different materials that were in the collection. I was also helping Karen Bubb, our Cultural Planner, with the traffic-box program. It was beneficial because I got to work with everybody in the department, essentially.

BB: The Arts & History Department just came together in the last few years, correct?

KLC: In 2008, it was formerly recognized as a department. I spent a lot of time exploring the back-end files and they tasked me with photographing the public art collection. At that point, the photographs we had were low-resolution. We didn’t have anything usable, nothing that we could put out in print. I got to go out and visit all the locations for every single work in the collection, which was—if people in Boise haven’t done that, take the time to go out; see the public art in the city because there’s a lot of it and it’s really varied and you get a really interesting tour of the city that way. So, I got to really familiarize myself with the operations of the department but also understand where I wanted to fit in. Karen had tons of projects going on. Things sort of shook out and I ended up getting hired as her assistant.

BB: And what was her title at the time?

KLC: She was Public Art Manager. I started really getting into the process of public art, which is not as glamorous as people think it is. We’re doing great work for the city and fortunate that they fund what we do. But just to have the opportunity to work between non-artists and artists—it’s always a challenge, a good challenge. I’m always learning, continuing my education. The process of public art really relies on contracts and purchasing and procurement law.

BB: A lot of paperwork.

KLC: And legal implications and developing contracts. But the other end is a visionary position where you’re working with planning and developers and partners in the city to identify opportunities and locations for art projects. It’s definitely a multi-faceted thing.

BB: That is so exciting. You started out as the assistant and now you’re the Public Arts Manager.

KLC: Well, it’s pretty exciting because Karen was able to move up in her position as well into the city’s first Cultural Planner.

BB: And that is brand new position?

KLC: A brand new position for the city. Not unprecedented in other cities that have robust cultural funding. I am beginning to realize that this year is a huge one for me. One of big change and new beginnings. I was told that my 27th year would hold many changes for me and of course I was skeptical, but it is fulfilling as we speak. On a professional level I have been tasked with taking the helm of the City’s Public Art Program. This is a monumental task, but one that will allow me to have a direct impact on the way that our city evolves and continue to engage with our arts community. It is daunting to say the least, but exciting at the same time. There are endless possibilities, but very real responsibilities. Moving through the transition into a managerial role is, I am finding, contradictory in many ways. Personally, I am getting married this year. This is not so much change, but a new beginning. It is a life-long commitment and is exactly the kind of stability I need to balance everything else in flux. It seems to be this rush of new; an avalanche. The tides are turning. Challenges abound and I could not be more ready than I am at this moment to face it, directly.

BB: You have good energy, Karl. People have asked me, where does the money come from for public art?

KLC: The public art program is run on the Percent for Art Ordinance. It’s a pretty popular model for a lot of cities that fund public art. When the city generates a capital project, which is anything deemed infrastructure—so, we’re talking like sewer lines or if the city were to construct a building like a new fire station—we get 1.4 percent of that entire capital budget for public art. The one percent goes towards the actual implementation and hiring and commissioning of an artist, and then the point-four goes to the maintenance and care. So, if it’s a hundred-thousand-dollar project, we get, I don’t know about twelve thousand-ish. The Percent for Art Ordinance is a long-standing [model]—some of the earliest programs are in Philadelphia and Chicago.

BB: Do you keep an eye on other city cultural departments and arts programs?

KLC: Definitely. When I first started, I provided research based on a list of peer cities.

BB: Yeah, we want to know who our peer cities are!

KLC: They range from Portland, Salt Lake City, Austin, Texas, Boulder, Louisville, what else? Knoxville, Tennessee. Some places you wouldn’t think would really match up. Some of our best competitors are Salt Lake City, and Spokane, Washington.

BB: I have to point out that you used the term “competitor.” Do you feel a little bit like you want to out-perform other cities in art? It’s okay to say “yes.” [Laughs]

KLC: I mean, yeah, I don’t know if it’s a competition, but yes in terms of innovative ideas, or innovative approaches to what they’re funding, the types of projects that they’re funding. Social practice is growing in acceptance in public art programs.

BB: What is social practice in terms of something that can be funded?

KLC: I think social practice is a project that’s conceptually based, that doesn’t result in, you know, a twenty-foot steel sculpture. It could be more program-based or it could be more ephemeral or temporary projects.

BB: Like the Sesqui-Shop.

KLC: Exactly. There’s examples of pop-up community centers where the artist creates the center and programs it for a [limited] period of time to activate a neighborhood that’s been forgotten about.

BB: Oh, I love that.

KLC: Projects like that are really interesting; they’re putting the money in the hands of an artist to better the community, but not resulting in what some people may traditionally consider public art or even art in general.

BB: How can you call it art if there’s no object, right?

KLC: Right. So, I think the Percent for Art Ordinance is really focused on generating capital projects. Using capital money means it has to be permanent infrastructure. I think, as public art evolves, there are some limitations that in my time I’d like to at least look at and have that conversation of what can public art look like? What form does it take? What’s acceptable?

BB: And how does it activate a neighborhood? I’m excited that part of your vision as the new Public Art Manager involves expanding expectations of art in the public realm.

KLC: Right. Ultimately, I mean, I show up to work every day and I’m happy to be there. I want to be there.

BB: You can’t beat that! You’ve studied abroad in Italy and Japan, you have a degree in art history, art education, and printmaking. You have your own studio practice and you teach art workshops. Could you possibly have time for anything else?

KLC: Yeah, I also serve on the board at Surel’s Place.

BB: [laughs] That’s a lot! If I had gone back in time to where you grew up in New Hampshire and found eight-year-old Karl and said, “Karl, when you’re an adult, you’re going to be working on a trillion art projects and you’re going to be an artist.” Would you have been surprised?

KLC: [Laughs] Yeah. But in high school they had a really strong art program, and, I don’t know, I found refuge in the art classroom. Coming out of there, I knew I wanted to be a photographer. I was already taking a lot of photographs and working in the darkroom at school and stuff like that. Looking back, photography was like the gateway into art. It’s like an easy in, you know.

BB: [Laughs] Because of the instant gratification?

KLC: Yeah, exactly. But of course, my parents were questioning, “What are you going to do with an art degree?” They were highly skeptical. So, I said, “Okay, well, I’ll go into graphic design. There are lots of design jobs.”

BB: That’s funny because graphic design is not one of your degrees.

KLC: But that’s what I came out here to do. My father had gone to Boise State in the late ‘70s. I just wanted to get out of New England for a while and loved it out West. I had committed to Boise State without having been out here. I lived on campus and took my first design class. In the first year I was here, decided, yeah, that [graphic design is] not what I wanted to do at all.

BB: So you were out here and you were far away from the people whom you’d told you were going to study graphic design. You tried it, didn’t like it, but kept going with photography. And photography is also not one of the degrees you earned! How did that happen?

KLC: I got hired right away at the university for photography. It was very commercially driven; we were working for the promotions office, the marketing arm. I was shooting events and shooting portraits and I got bogged down with photography. I was doing it as work, you know. Although it was a great job, it became an obligation; in my mind, I wasn’t able to approach photography creatively. I could only see it through that lens of having to generate content.

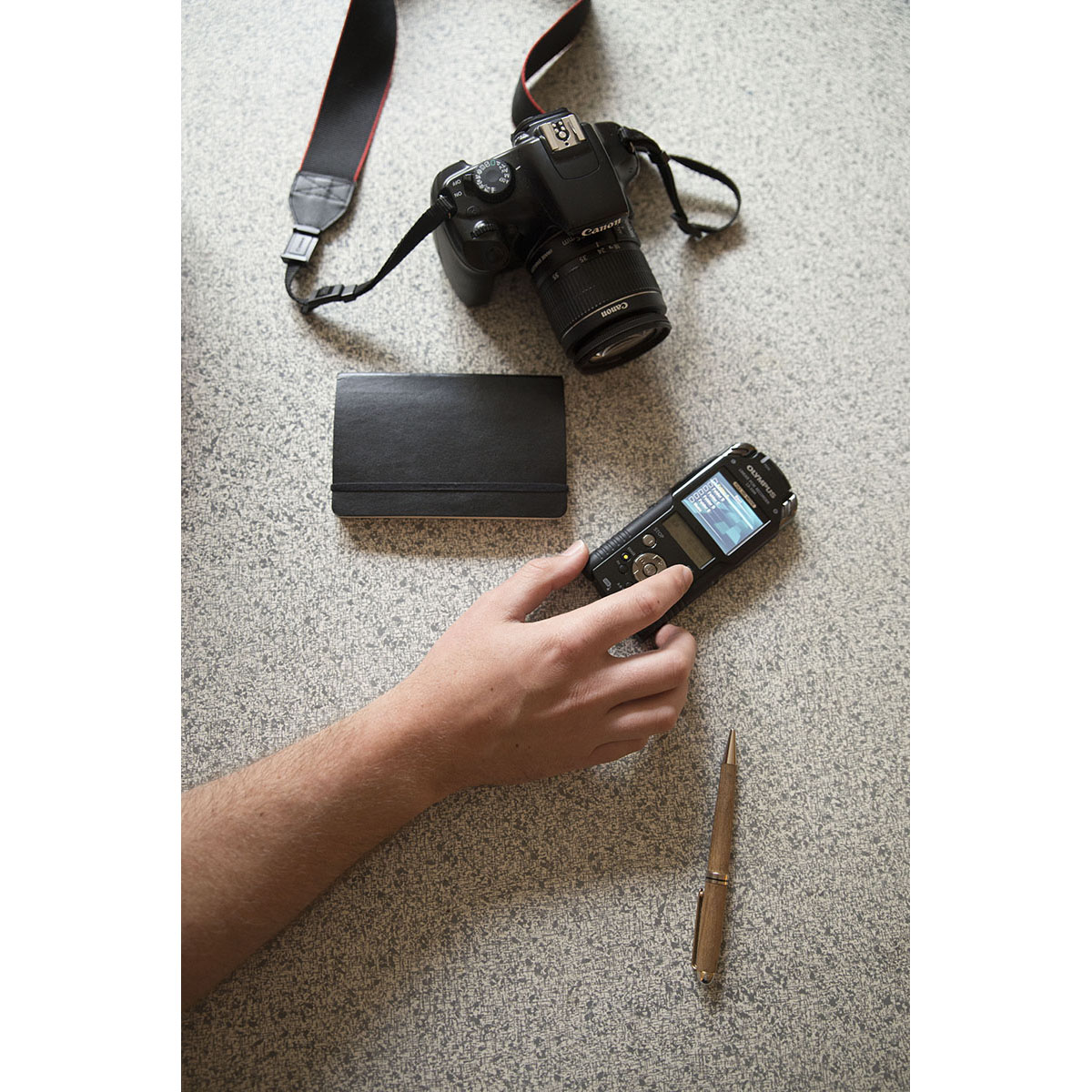

BB: You were faced with a checklist of the shots you needed for marketing. That brings up the Creators, Makers, Doers interview series that is the content for the Arts & History Department blog. It was 2015 when you started the blog, how did you get people on board with your idea?

KLC: When I was working as the program assistant I was pretty busy with other things, but I didn’t have my own project. Amanda Ashley and Leslie Durham—two professors at Boise State—put out a big study. They went out and interviewed a bunch of artists and they put out this high-level numbers-based report. It was all about statistics of Boise’s creative economy. But they didn’t identify who the artists were. It’s like, okay, that’s great good information for the City to use, but for the average person, who are these artists? You know, what are they doing? What are the projects that they’re working on? I started developing a number of ideas on how we could look at the disparities in the gallery scenes and opportunities to show work. [I was] looking at how we can foster a more philanthropic community or a collecting community. The blog grew out of the process of trying to find a way to highlight the artists that we were working with through the department. At the time I was reading this other blog coming out of Germany that interviews creative individuals—“Freunde von Freunden,”

BB: “Friends of Friends” in English.

KLC: Yeah. A really beautiful blog; they have a ton of money to produce it. But going along that same line of meeting people in their spaces, documenting their space, documenting their practice, and what their ideology is about—making art and what it means to be an artist in Boise.

BB: So, you proposed, “Hey, I want to do a blog kind of like this”?

KLC: Yeah, so I showed everybody the blog I was looking at. It was like, “So, can we do it?” And they said, “Yeah, absolutely, sure.”

BB: After your promotion in February this year, your new responsibilities crowded out your project. The blog got put on the back burner and eventually you realized you were going to have to pass the torch, so to speak. How do you feel about that?

KLC: Well, I have plenty of other work to keep me busy [laughs]. The blog has been pretty successful. It is the most heavily hit item on our Web site. I guess people like to read it [laughter] and check it out. I think it’s nice, you know,—[Boise is] a pretty small community, but I don’t think people get that intimate moment with someone that they know as an acquaintance. You get a little bit of a perspective.

BB: Have you noticed whether some of our peer cities have done something similar in their arts department or do you feel like you’re pioneering this?

KLC: I haven’t really seen anything coming out of any of those programs like it. Some of the cities do more artist-talk series, where they have the artists in a forum. Like the Fettuccine Forum, but I haven’t seen anything quite like [Creators, Makers, Doers].

BB: So, it’s your baby.

KLC: Yeah.

BB: Well I’m very excited to carry on your vision and I’m proud of what you’ve built up for our creative community here.

KLC: I’m just glad that it will live on because we work with so many artists in the community and I didn’t have a chance, obviously, to cover everyone. And the pool just continues to grow as we continue to grow in the department.

BB: Exactly.

KLC: And, you know, I think everybody deserves to have their time.

BB: I think so, too.

KLC: Do you want to talk about your interest in being involved with the interview series?

BB: Sure, I am in love with your baby! The idea of visiting artists in their studio and photographing their space is something that, from the beginning seemed an ideal fit for me, the perfect subject for using my skills outside my art practice. Karl, you are in photography, I’m sure people have asked if you do weddings. While I am interested in seeing what people are doing with weddings and portraits and interior photography, and I appreciate that work, I don’t feel like it is the right fit for me. When you first started doing the blog, I remember, I had just gotten my digital camera and you contacted me about an interview, which we are now doing three years later. [laughs]

KLC: Yeah, it’s been a while. I was thinking about that earlier.

BB: I had emailed you, “Hey, I just got a new camera. If you need help with the blog, I will be there.” Your idea appealed instantly to me. To talk with artists and be inspired by their process is a dream come true. It makes me very happy to contribute to what is now one of the few arts publications, especially since Latitude ended (the quarterly journal published by the Idaho Commission on the Arts)

KLC: Can you talk a little bit about your approach to the blog and how it may be similar or different to my approach?

BB: You mentioned before that you felt you could talk at length about the philosophy behind art and going into conceptual detail. I am at a point in my life where I am more interested in the personal side. While I do want to ask questions about concepts and larger theories of post-modern art, I really want to ask, “So, if I went back in time and told your eight-year-old self that you were going to be an artist, would you have been surprised?” I think my approach will be more on the human-interest side.

KLC: I like that. I think it will be good—a good change. You are also an artist; how do you describe your art-making practice?

BB: My art-making practice is something that gets crammed into nooks and crannies of time that I have alone. I didn’t realize that I needed so much time alone to make art and just to feel human! When I got out of graduate school in 2009 I started a family right away and I haven’t had much alone-time since then. Usually when I make art it’s very short but focused and I can be surprisingly productive in a small amount of time. I had to quit working in film; up until a couple of years ago I was still shooting medium-format color film and scanning it and printing it digitally. I do not have time to scan negatives; it’s a chunk of the process that I could eliminate by going digital. I’ve been inspired by the technology of photography itself—like Instagram and selfies and smartphones. I’ve been making photographs of photographs, which is nothing new. Maybe making 4×5 black and white paper negatives of a picture on a cell phone is kind of new. That is an example of the work I was able to make at the Atlanta School last summer with Amy O’Brien, Rachel Recheirt, and Jon Sadler. I’m responding to the world of the selfie and social media but putting it into a fine-art setting.

KLC: What’s your draw to photography?

BB: You already said it, it’s the gateway into art! I love paintings and I wasn’t bad at painting but I wasn’t good either. I kind of wish I were a painter, but I’m not. And I kind of wish I were a sculptor because I love sculptures themselves and I love working with my hands. Recently, at the Boise Art Museum I was working in a studio setting and I decided to tackle stop-motion film. I made three short animated still-lifes. Which is kind of funny. But that process took so long; I had to shoot five hundred photos in a row while moving objects a quarter of an inch or less each time. To be honest I got bored. [Laughs] I’ve realized that my attraction to photography is its immediacy and maybe I’m impatient. Yes, I think I’m impatient. That says a lot about my personality, but in photography I’ve been able to realize my vision more than I was able to in painting or sculpture.

KLC: Is your primary focus in subject matter still lifes? What kind of objects do you find yourself gravitating towards in still life?

BB: I have been focused on still lives for about seven years. This is kind of embarrassing- but I think it’s because I can control all the pieces. Still life work is a little stage that I’ve created and I get to tell everyone what to do. It brings out an aspect of my personality that isn’t my favorite: I like a little bit of control. You put that together with impatient and maybe you get someone who doesn’t work well with others? [Laughs] I’m also looking forward to doing some landscapes, and I’ve been getting back into photographing people, which is where I started. I went through a period of social withdrawal before I earned my MFA. There was a painful time in my late twenties when I was stuck in what I would call latent identity formation- something that should have happened in my teens. I shut down my interactions with people and photographing people because of intense insecurity and fear. Opening up to friendships and being vulnerable is one of the best things I’ve learned in life, and I certainly had to learn it. But I still struggle. As for still-life objects, I’m attracted to anything miniature, or things where scale is different than what you would expect, such as the world’s largest pair of underpants that I saw in St. Louis. I’m attracted to novelty. My favorite place is called the City Museum in Missouri. It is the creation of the late Bob Cassilly, and there is nothing like it. I can’t even describe the kind of high that place gives me. I tell everyone to go there.

KLC: You said you transitioned out of film. Can you talk about your feelings about film versus digital photography?

BB: People love this question! What I think is that digital photography is just another tool, people can use it to make great art or they can use it to make snapshots or family photos, just the same as the film processes. Sometimes people have a tendency to put a higher value on works done on film or traditional darkroom paper but you can find gobs and gobs of old black-and-white snapshots that are terrible. Really terrible. But I am not finished with film. I’m trying to mix it up, I’m trying to jumble all these processes together: film, digital, color, cell phone pics, Polaroid. But I don’t think one’s more valuable than the other.

KLC: The medium doesn’t necessarily dictate the kind of work that you’re making?

BB: Right. The medium isn’t going to dictate what the product looks like, the person behind it is going to dictate what the art looks like.

KLC: We talked a little bit about your involvement at the Boise Art Museum; it’s a pretty big honor to have that opportunity and have work selected for the Triennial.

BB: I am so happy about that! The Triennial comes up every three years and I’ve applied four or five times and I’ve been accepted twice and rejected the other times. This year I was one of the six artists selected to do the Artist Lab: you set up your studio inside the museum and you make work there for two months. That was precious to have another pocket of time. At the museum last month, I shared the studio space with painter Geoff Krueger. Actually Geoff and I live across the street from each other. We have a lot of artists in the hood: Jill Millward, Rachel Teannalach, Laurie Blakeslee, Jill Lawley, Peggy Jo Whilelm, Charles Gill, I’m sure there are more, it’s pretty awesome. Anyway, in the Artist Lab I got to watch Geoff’s process; right now, he’s excited about these objects he’s finding on the street or in the gutter, such as partially crushed cardboard that would normally be trash. But he’s making them into collages that are very beautiful and quirky and minimal. I had that artist feeling, I’m sure you’ve never had it [laughs,] but it’s like artist jealousy, when you see something and you really wish you’d thought of it first.

KLC: Yes! You touched on it a little bit, but tell me about your process. What does it look like in terms of generating ideas or actually getting to a finished product?

BB: Usually my ideas come to me while driving or during yoga. But making the work starts with cleaning the studio. I plan to come downstairs to work, but “Oh, this—I cannot work in these conditions. This has to be dusted. This has to be organized.” There’s forty minutes of fiddling and shuffling things around until I can get into the zone. There’s also a prep period dedicated to making snacks. The second hour is spent setting up my camera and setting up a still life. It’s only in the last hour that the work is made. Eighty percent of the time is spent going in circles around the idea of making art and then twenty percent of the time is spent making the art. [Laughs]. And then occasionally, creative magic happens in the last 1%.

KLC: Yeah. That seems pretty consistent. [Laughs] What would be an ideal venue for you to show your work? Where do you think you fit in?

BB: That’s a really hard question. Fitting in is like a lifelong lesson for me.

KLC: [Laughs] I’m just setting myself up for later, so you can ask me the tough ones, too. I’m reconsidering some of my questions–

BB: Yes, I have some hard questions for you, too. But to answer, I had a solo exhibition at the Student Union Gallery at BSU and I think a really great stepping stone for me would be similar galleries at other universities out of the state.

KLC: So, that kind of gets into your opinions, feelings, about the arts community here.

BB: I think that the arts community is expanding at a rapid rate since we’ve come out of a recession. There are so many artists’ collectives at this point, it used to be you just had BOSCO (Boise Open Studios.) And the recession drastically shrunk the number of galleries. But post-recession there has been a number of other collectives that have jumped up and people are working on collaborative work spaces, like your studio in Garden City. But I don’t know that artists are able to sell work in Boise. What I think could help is, in the same way that the City provides workshops for artists, could there be some kind of publication for people interested in purchasing art? Like, the people’s guide to buying art. Could it help stimulate the art-buying community by listing established artists in Boise and different styles of art available and price ranges? Something to give potential art buyers confidence in making a purchase. I can’t think of anything more personal than choosing and buying art. It’s so subjective and it can be a big investment. A guide could relate information like how to budget for art acquisitions, how to research artists, and how to develop your own personal taste, step by step. Not that I know what those steps are.

KLC: That’s a great idea. Definitely.

BB: I’m kind of proud of that idea. I think my biggest fear as an art buyer is, what if I don’t like the art later? What if I’ve invested five hundred, eight hundred, twelve hundred dollars and then in two years I don’t like it anymore? Or, what if people come into my home and they think the art is terrible or that I was foolish to buy it? Maybe this is my insecurities talking, but I don’t think I’m alone. [laughs]

KLC: All right. do you have any words of inspiration for other artists out there?

BB: I still feel like an emerging artist so I don’t feel qualified to give advice. But the book called Art & Fear has been a tremendous help. Have you read that one?

KLC: Yes.

BB: It’s about how my main block to making art is myself and my own fear—fear about where the art will be shown or who the audience is. Or where I fit in, for that matter. In a nutshell the author says, “Just put your head down and do the work and let the rest fall into place.” I spent a lot of time early on focusing too much on applying for exhibitions how and building my resume and less time on actually making art. My best advice to myself is, “Put your head down and do the work.”

KLC: Yes. Even if it’s twenty percent of the time?

BB: [Laughs] Yep.

BB: It’s my turn to ask you some hard questions. You have been on both sides of the coin: the artist and arts administrator, how is that?

KLC: I think this one can be summed up with one word: empathy. Having been and also now bridging both sides, I have a better understanding of what both parties are expecting from that relationship. As an administrator, it has been easier for me to work with the artist process, as that is something that I engage with personally. I know the time it takes to develop ideas and concepts and that allows me to be more flexible in my approach to working with artists. I also understand what processes artists typically struggle with, so I have worked hard to better inform myself, as an administrator, so that I can properly assist and educate the artists I am working with. Being an arts administrator certainly does not require an individual to be an artist, but having that background is a definite advantage. As an artist, I have become more aware of the work it takes to provide artists with opportunities and have recognized my personal practice as more of a business and have tried to become more professional so that I am not creating issues for the administrator that I am working with. It all flows back and forth and good communication and respect are always warranted.

BB: Those are good tools for people in all walks of life. Earlier we talked about your switch away from photography to printmaking, how did that happen?

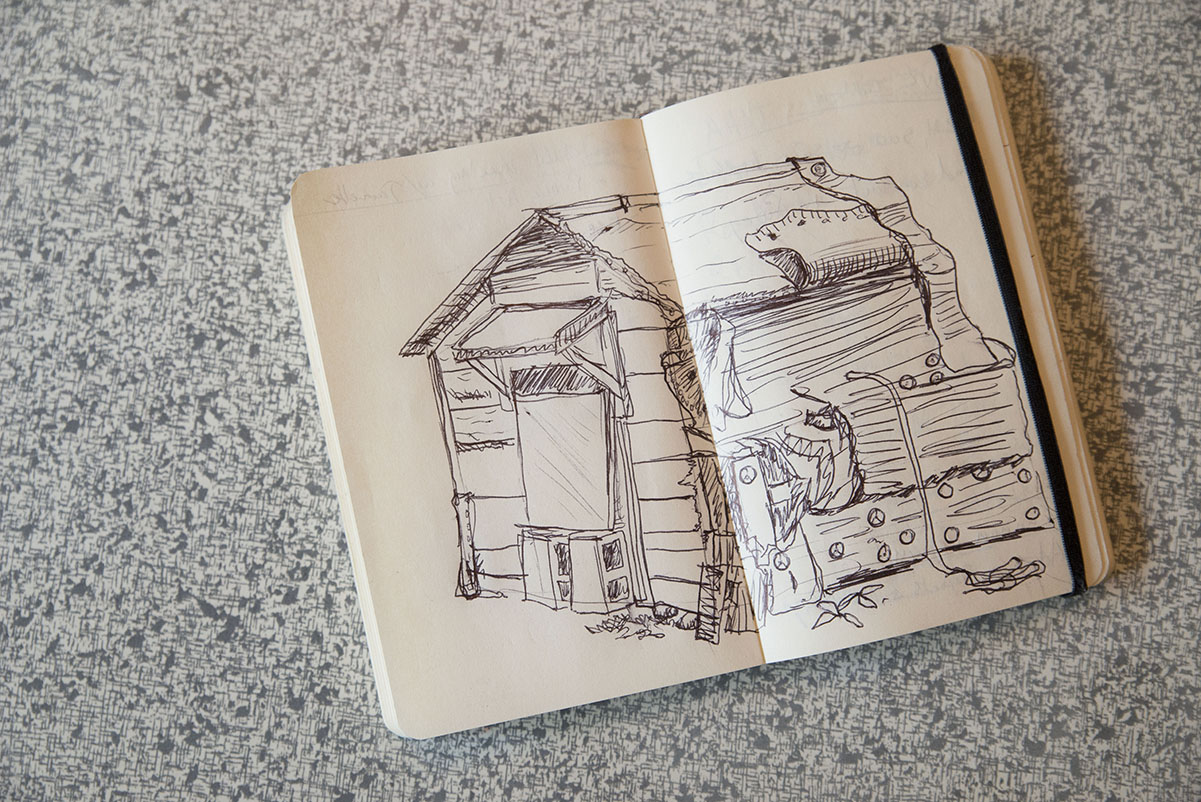

KLC: At that point I was interested in drawing and I draw a lot, but I don’t feel like I’m super-technical. Printmaking is an indirect process, where you’re working on a plate as opposed to the finished product. You have more time to generate your ideas and to work out the ideas and how you’re going to represent something in the process of creating that plate. Something about how it’s so process-heavy, you’ve got to create your plate, you have to go through a certain process to ink the plate and then print the plate, and tearing the paper down and mixing your colors and—

BB: Did you find that that long process was sort of like meditation?

KLC: Yeah, absolutely. It was interesting. There’s a certain hertz that your brain operates in which people are most creative. It’s something like 5.7 hertz. When you’re sleeping, it’s like 4.8, and when you’re dealing with challenging tasks, it’s like 6.2. So that 5.7 is somewhere in the middle.

BB: Not awake, but not asleep. More subconscious?

KLC: Right. Going through the process of tearing paper down or, I don’t know, incising a thousand lines into a copper plate, your body is busy but your mind is free.

BB: You recently had a solo show at Boise State titled “Phenomena.” Could you describe it?

KLC: It was composed of a series of copper plate engravings, which was a new process for me at the time and some large-scale mixed-media drawings, which was also new. And a sculptural installation. The installation was conical-shaped concrete forms that were arranged in a sort of a mandala or medicine wheel arrangement. Abstract, but the idea of a landscape or a ritual space.

BB: Stonehenge comes to mind.

KLC: Yeah, around England and France there’s remnants of monoliths and it’s totally speculative on what the use, the function of these spaces, were. So creating a space like that; the imagery was related to what sorts of phenomena might happen in that space. But then “Phenomena” was more about what kind of mental state or physical state you are in when ideas occur. What generates ideas? [I’m] trying to capture the feeling of something that you can’t explain. That feeling, the spark of an idea.

BB: People ask artists, “Where do you get your ideas?” And often the answer is “I’m not really sure.”

KLC: Right. As an artist, the best way to explain it is to make work about it, because it’s difficult to describe in words, you know. One of the copper-plate engravings [in the show] was of a thunderhead—a cloud that would generate a thunderstorm. [A thunderhead] has multiple meanings or different readings into what it could represent.

BB: Maybe for prehistoric people a thunderhead wouldn’t be about precipitation and static energy, right? It might have been an omen.

KLC: Yes, some sort of omen, some sort of sign, a representation of something more powerful on this Earth. Like, Zeus and the thunderbolt or just some other sort of natural phenomena, like an eclipse.

BB: The eclipse is coming.

KLC: Right. [Laughs]

BB: We will be out there in August, maybe making ritual spaces or enacting some kind of ritual and watching the eclipse with our glasses on. It’s not mysterious to us now but to cultures in the future, it might appear obscure. When you talk about phenomenon, I’m thinking of ghosts or foreshadowing in life.

KLC: Yeah, my mother is very into ghost stories.

BB: Oh, I love ghost stories.

KLC: Especially growing up, I feel like New England- there’s so many old ghost stories and haunted places. I’ve had those experiences. That sounds, you know, to some people it will sound very crazy, but—

BB: To some people it will sound crazy, but not to me. I know enough people that have had unexplained experiences and I trust what they’ve been through. I married into a family that sees things all the time, visions of the future or figures in the mist. I don’t see anything. Nothing. I’m jealous.

KLC: I’m also interested in talking to people about past lives. You know, you run into someone that’s a total stranger and, “Ah, somehow I know this person.” [In Japan] I had an immediate connection with the woman I was staying with. It was weird. I didn’t feel like I had to put any walls up or anything. We were sitting up one night drinking wine and she’s a Buddhist and so she very much believes in past lives, that’s part of their culture. She started talking about how one of her favorite past lives was when she lived in France in the late seventeen hundreds. And at that moment, I just felt compelled, and I said, “Yeah, me, too.”

BB: Had you felt that before?

KLC: No, no. It just came out. And I still get chills when I tell that story.

BB: That is a phenomenon! Does that story inform your art making?

KLC: Well, so, then I started having these, I don’t know, not yet dreams, I guess, of like—being a printmaker in France.

BB: Chills!

KLC: Working at a litho studio in France in that time period. There’s certain things in the [litho] process that, you know, feel just too familiar.

BB: Muscle memory?

KLC: Right. If muscle memory can transcend time.

BB: For sure. Wow! When you’re making artwork, do you have something that repeats itself, like a pattern or–?

KLC: Yeah, I think there’s forms. Certain forms that, I don’t know, still show up. It’s like an organic, sort of circular, ovoid form that I’ve been exploring for the past couple of years.

BB: It just keeps coming back?

KLC: Yeah, it keeps coming back. It’s opening up into other things, it’s evolving. But, I don’t know, there’s been certain things that, if I put a drawing utensil to paper, it just comes out. I used to get frustrated with that, but now I’ve really embraced it in that that’s just part of [the process.]

BB: You’ve learned to follow instead of try to direct? Allow your intuition to lead?

KLC: Yeah, definitely more intuitive.

BB: That’s curious and intriguing. I just have one last question, which is the quintessential Karl question: Do you have any advice for other artists?

KLC: [Laughs] No, I mean, well, I moved out here to get a degree in art and there’s a lot of people who were highly skeptical. And I think what served me best in my time is just working really hard. If you want to do something, work really hard at it. As an artist, it’s really important to diversify your skill set. I pursued education, I pursued art history, I pursued printmaking. Am I fully equipped to be [laughs] doing the job that I’m doing now? Not fully. I’m learning everything, new things about process and public art. I’ve got a stack of books this tall next to my bed that I’m reading furiously to educate myself. It’s important to be open to what it means to be an artist; it’s easy to pigeon-hole yourself: “I’m not going to do anything other than draw and paint.” In today’s economy and culture, it’s really, really, difficult to do that. That’s a romantic idea.

BB: Better to say “I can teach a workshop. I can organize a workshop. And I can make the art. I can do all of those things.”

KLC: Right. I lived it, but when I was eight years old or even when I first came to Boise, no way could I have said that I was going to be managing the public art program here.

BB: It’s very exciting and a big honor for you. The skeptics of your past must be very proud.

East End June 9, 2017 Portable Works Collection

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.