Creators, Makers, & Doers: Dwaine Carver

Posted on 10/8/18 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

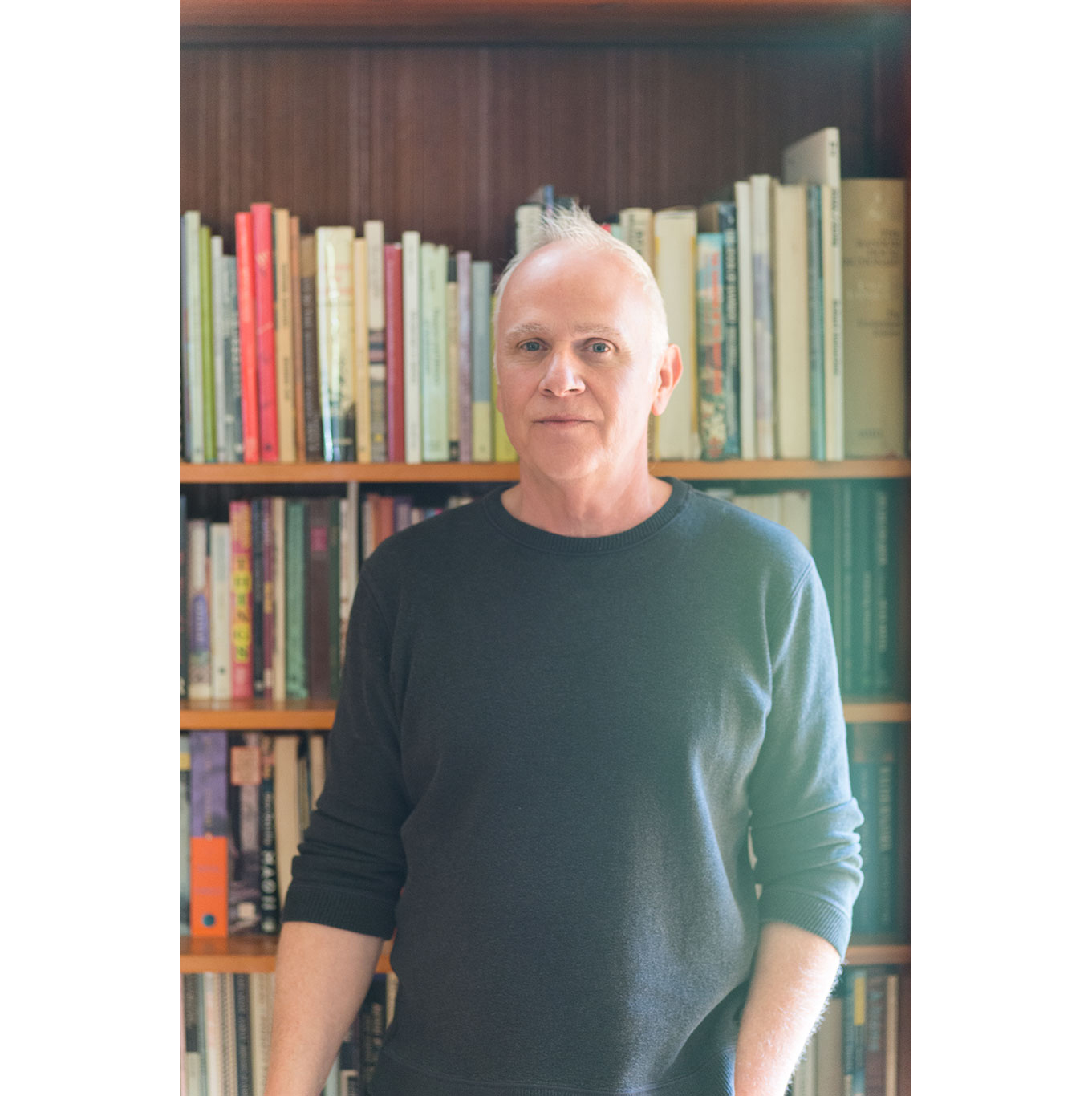

Dwaine Carver is a designer, educator, and artist whose extensive Boise WaterShed Arts Plan, completed in 2009, provided a blueprint for the types and potential location of artworks to be installed on site at the wastewater educational facility. His large sculptural collaboration Cottonwoods can be seen on the new Boise City Hall Plaza (find out some back story to the new plaza below) and another, Heliotrope in BODO. You might spot Dwaine on the fourth floor of the University of Idaho Urban Design Center where he teaches architecture, or at his workplace: CTY Studio, or somewhere in between, cruising around town in his 1960’s Ford Falcon—possibly listening to an 8-track tape. Dwaine has a wide range of influence with students and creatives and when his name comes up the word ‘brilliant’ usually gets tossed around with mention to his singular style (a blend of minimal and mid-century topped with a bit of nostalgia.) Our conversation is a deep dive on the liberal arts, and we’ve heard his formal lectures have been known to induce the sensation of an intellectual high. Dwaine speaks with a precision and complexity of thought that inspires a desire to slow down and look closely; look for the unseen and there you will find the art.

We are sitting outside on a perfect pre-fall day, enjoying the sunshine. You and I know a lot of people in the same circles, but we’ve never really sat down and had a conversation. You’ve surprised me because you said you grew up in Boise, but I’d already made up in my mind what I thought I knew about you, which is that you aren’t from here—

[Laughs]

You went to Harvard?

I did. For grad school.

Tell me about the journey from Boise to an Ivy League school.

Yeah, that’s kind of interesting. When I decided to go to Architecture School, I’d already sort of flunked out of some art classes by virtue of neglect, and had gotten married, had a child, ran a nightclub after having driven a Pepsi truck, stuff like that. I was always interested in cultural production items—writing, fine art, design, and decided architecture would enable all those things. It was a really nice synthesis and I wanted to get more serious about what I wanted to do with my life. I decided to go to architecture school; applied to several, and to my surprise got into RISD (Rhode Island School of Design) and also to my surprise received a lot of money—the admissions committee obviously liked me for some reason, so I went there. That was a leap for me.

That’s a big leap.

The Idaho boy. I was eight years older, more or less from the typical students coming in. It was because of the RISD stuff that I ended up at Harvard, as well.

They liked you for some reason, too? [Laughs]

Well, the two institutions are connected in a lot of ways.

Was it a natural progression?

The Rhode Island School of Design, I chose in a pragmatic way in terms of wanting to get more serious and have a craft or profession. Harvard was much more self indulgent, I thought. “I’m going to do this just for me. I don’t think I’ll ever cash in on this in some way…”

You didn’t feel it was as pragmatic a step as RISD?

I didn’t need to go to Graduate School. I wanted to go to Graduate School.

You said you weren’t expecting it to pay off. Is that still true?

No, I don’t think that’s true. I think it’s another badge, another credential that—in fairness or not, opens certain doors or inspires some faith. I think it closes other doors, too. I mean maybe you assume that I didn’t grow up around here—that I grew up with more money because of that association.

That’s a good assumption.

Yeah and neither of those things are true at all. At all.

You described the decision to study architecture as a logical process because it would marry all these things: writing, fine art, and design?

I was also interested in journalism and literature and thinking I would like to teach it. But I realized it was cutting out all the visual art and design, so I decided to lop it off the other way. I felt like architecture also has narrative embedded; the discipline and the culture of architecture has a literary history and literary component to it so it really felt like something I could shape. Something that I want to shape.

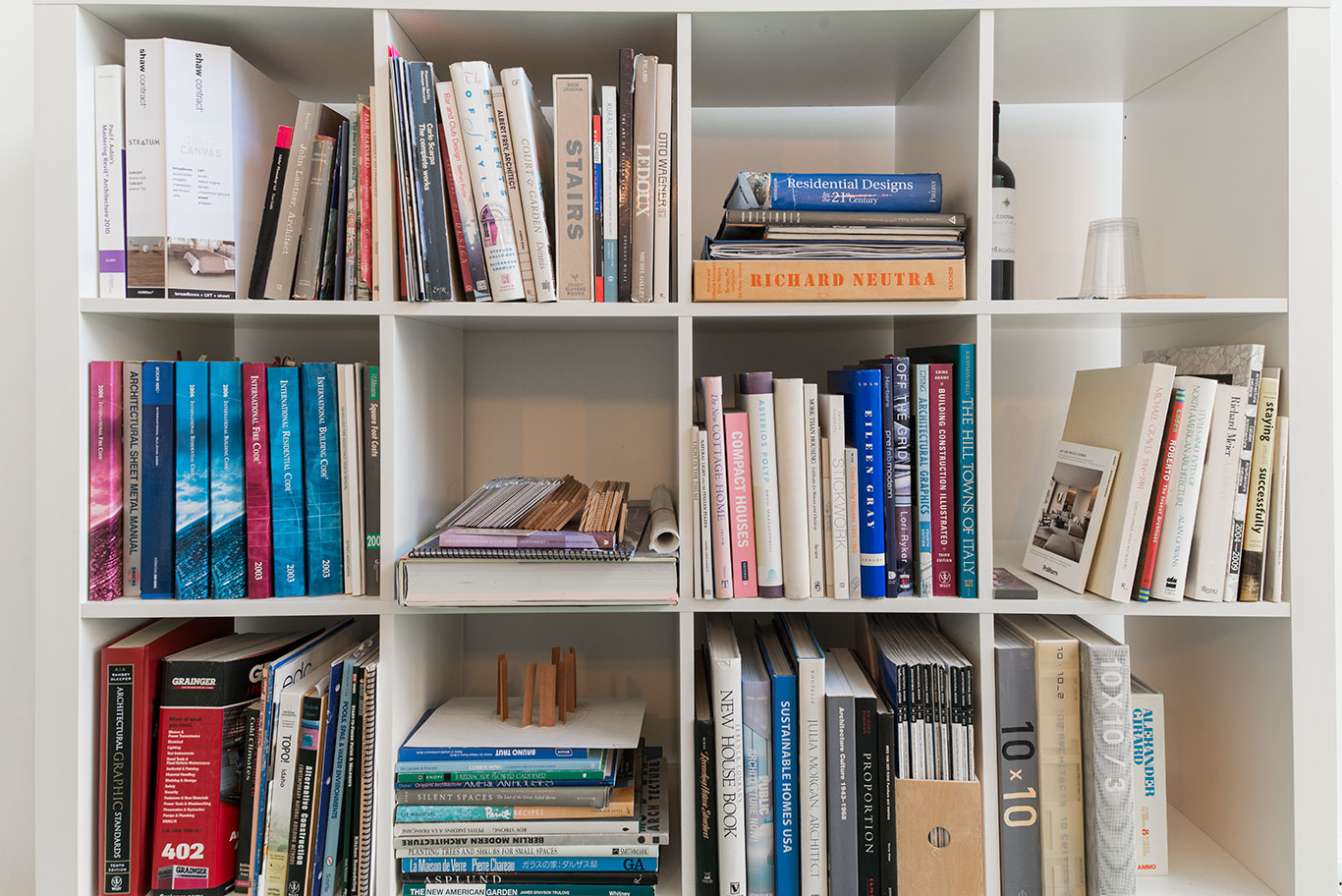

You and partners Rob Thornton and Elizabeth Young started CTY Studio, an architecture studio in 2012, and you are an Assistant Professor with University of Idaho’s architecture program here in Boise.

I’ve always had one foot in academia. CTY enables that balance of teaching, architecture, and art.

What do you like about teaching?

Returning to first principles all the time. It’s something I like looking at. It’s worth talking about line again. Line is endlessly fascinating. And I like my colleagues, I like the interactions with students. It’s like continuous grad school, I usually have to do research and figure some things out, refine them.

Let’s go back to when you chose architecture over literature. You said architecture has narrative?

There’s a couple of different ways to look at it. One really straightforward way is that all architecture is ritual and social lives concretized— made concrete and made into a thing we inhabit collectively and that is the narrative of our lives. So that’s the really straightforward answer. The more academic or esoteric answer is that there are certainly architectures that are made and driven by narrative: all the Enlightenment era visionaries who are actually writing a story with their architecture. Many of the Utopian architects doing ideal cities, that kind of thing, all the 20th century avant-garde—those are narratives to be read.

When you start occupying a space, that becomes the narrative?

Yes, or the narrative is being enacted just by declaring a place sacred—by returning to it, building a fire there. That’s architecture in the most profound and fundamental way.

Ok, let me marinate on that.

[Laughs]

You put a visual in my mind—I want to really understand, you said going to a place, declaring it sacred, building a fire…

Gathering there. By making that fire, drawing a circle in the ground—that’s architecture. That’s making the place. And declaring it. So everything that comes after that—any stacking of stones or any kind of shelter you make to keep the rain off the fire, so you can still gather, that’s making the act of architecture concrete. So architecture maybe isn’t the thing—

It isn’t the object?

Yeah, it’s the act and the intent behind it.

[Long pause] So, kids are doing architecture all the time.

You hide under the table as a child—

That’s all they do!

That’s right. That’s precisely right. So, get underneath the dining room table while your mother is setting up Thanksgiving dinner—that’s an architectural act.

You just blew my mind.

[Silence]

What you just described is so beautiful—I don’t know how to move on from there.

[More silence]

I guess we could talk about set design. You’ve designed stage sets for Boise Contemporary Theater productions?

I love doing those. It’s the narrative in architecture thing again, for sure. It’s a really concise problem. It’s like working for a client; an ideal client might be somebody who just wants a house, so you find out who they and what their life is like, and they have no requirements for the design. They have a budget—it can only cost so much and they don’t have any preconceived ideas—they don’t have a cut-out book with a bunch of images. A play is like that ideal client. There’s no preconceived idea about what constitutes these spaces.

On a stage you can really use the space, impracticably even, if you want to, to physically move characters through the story in a particular way. Actually, that’s true for regular architecture too.

Architecture is fascist, sort of, because it makes you—“Must do this, must do that, use that door, use a window this way, Etc.”

Fascist architecture, yeah, it really is! [laughs] Can a space be passive aggressively designed I wonder?

Yeah, you’re making an environment for these things to occur in, so there’s this other problem that happens: are you making architecture or are you making a building?

What’s the problem?

The problem is art, right?

[Laughs] That’s a whole topic. Let’s go there. Is this form vs. function?

There’s that. There’s always that. When building becomes art, when the act of building or ideas about building reach their apotheosis then it becomes art. You know, just like every picture isn’t art. Every drawing isn’t art, in my opinion. I think we have to make distinctions…

Because?

Because it has to reach a level of thought—

Intention?

Art can be unintentional, too, but I think there’s a level of thought that has to occur. A gesture can be art and I think people make art, even unconsciously, all the time. Art exists in a lot of different ways. I think the artist’s job is the identification of things that are unseen by others. That is maybe one of the principal tasks of an artist, to make the unseen seen. Not to accurately represent what is seen, right? So if you can state an intention and marry it to an object or representation you’re making, and there’s the perfect alignment and execution of all those things—that seems an unlikely scenario for art to occur. Because it’s all preconceived, it’s all mapped out.

Is it missing the magic?

Yeah, right. Maybe a gesture, a movement, a thought, the accidental placement of something, any of these things could become art, but most of the time we make pictures, or buildings, and declare them art, and maybe I’m just being mean, but it’s sometimes easier for me to look at a picture and discount it, to be harder on the picture, more skeptical of it as art, and more accepting of the simple or accidental gesture.

It might be something about the fleeting nature of a gesture, that you don’t have time to second guess your instinct?

Yeah.

Talking about accidental placement, and gesture, are there artworks that come to mind?

Well, I was certainly thinking of Milan Kundera who writes this really beautiful piece titled Immortality. He makes a novel out of a gesture, the opening scene is him contemplating the gesture of someone turning and waving. The novel unfolds from that moment and it’s almost like a manifesto on literature, it’s like a thesis. And then the gesture in art, who is this guy’s name? An artist that has done multiple kinds of actions: walking through a city dragging a block of ice until it’s melted, do you know who I’m talking about?

I’m thinking of the guy who had a line of people, like a mile wide with shovels, who essentially moved a sand hill one foot south by shoveling the sand, or something like that.

Same artist!

What is his name? He lives in Mexico. Francis Alÿs!

Yeah, thank you. I think people can do things accidentally or unintentionally—or maybe someone with OCD or something—can do things that are, in all likelihood, a kind of pinnacle of human expression.

Basically, art is happening all the time, everywhere, and especially by accident. But the magic is in actually seeing it.

Yeah.

You’ve really got to slow down for that to happen. You’ve also got to slow down to look at art and to get inside the shoes of the artist. Why are they making this and why do I care?

Right, right.

I have a hard time slowing down like that.

I think most people do. It’s a contemplative thing. I think maybe all the things I’m talking about right now are of a very contemplative mode. I think there are other modes that are just as legitimate. I am maybe more likely to focus on the discipline of whatever it is that I’m looking at. When we were talking about the kinds of questions I like to ask artists, they are: ‘Who are you talking to?’ and more specifically, ‘Who contemporaneously are you talking to?’ and ‘Who are you talking to across time?’ That’s the disciplinary mode…

I’m going to try to keep up with you here. Go on—

Well, that’s a disciplinary mode. Because you’re using the discipline to speak to your contemporaries and you’re using the discipline to speak across time to other practitioners of the same discipline. Or at least that’s the way I think about it. Like, what’s the discipline, what are the stakes, what I am responding to, what are the influences? Am I picking up a conversation that’s already been going on? And am I contributing to it in some way?

Hopefully.

Yeah. Exactly. And so that’s probably the more conventional m.o. for most practitioners of art and design.

Alright, so, then the contemplative mode would be?

That’s using the discipline to dig deeper and question your own perceptions and think about the world as a larger kind of sphere. As opposed to the smaller spheres of disciplines.

We’re talking about an artist having an inner conversation with an imagined audience of peers or contemporaries. A more contemplative mode would be like—

Talking to yourself.

What else goes with discipline and contemplation?

Practice. I mean, architects use the term practice. I think that’s a good term, right? There’s the theory and the practice. And architects practice. It’s almost like they never really get to the event. I think that’s what all makers have to do: practice.

Practice is the hardest part. Let’s talk about “Cottonwoods”, the new public art at Boise City Hall. Let’s talk about your audience.

Talking to yourself vs. talking to the public.

Yes, you have to have both of those.

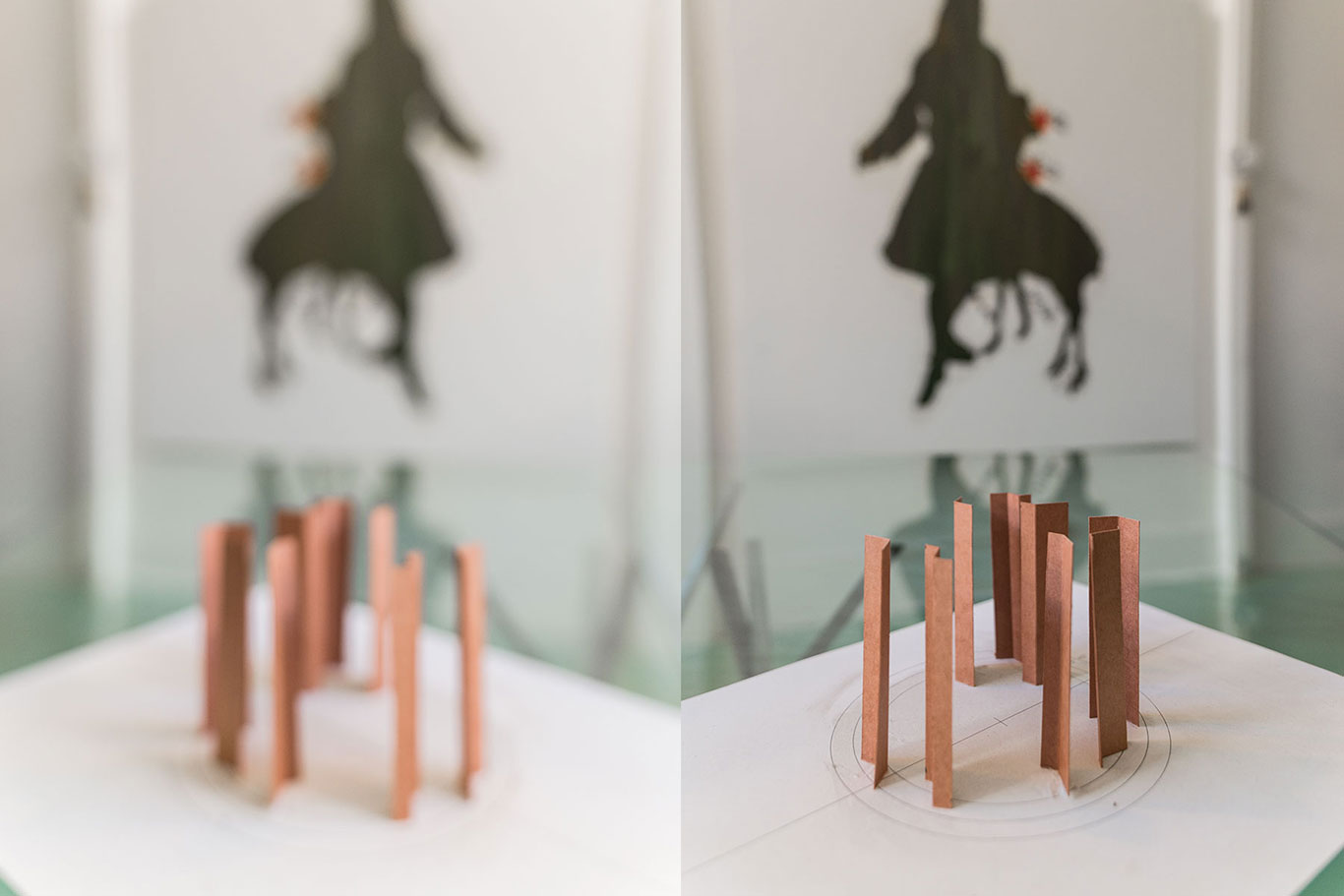

Right. First, like so many of my projects, it’s a collaboration. The “Cottonwoods” collaboration started with CTY Studio: my two partners Elizabeth and Rob and myself, and everybody at Ecosystem Sciences: Zach Hill and his partners there. They’re ecological planners, architects, artists and designers. Zach has an architectural education so it’s really easy for us to talk to one another; we have a lot in common. It’s the six of us first and foremost trying to figure out our approach, how do we want to enter this competition and propose artwork for the City Hall Plaza? Collectively we decided that what they were proposing as the site, the plaza itself, was inadequate. Our strategy was to redesign the site as part of our competition entry for the art.

With projects like that, the call for art always has to start somewhere, and it can be problematic when someone else comes in later after it’s finished and says, ‘Well, what you should have done…’

Yeah. So that’s what we did. We were like, yeah, we don’t accept this site.

Good for you.

We proposed an alternative site plan and an art proposal that goes along it. That’s how we won the competition. At some point, Zach and I became the two principal designers and artists of “Cottonwoods”. The context of the site is understood to be a kind of cross-section of the valley from the Boise front range to the river, and understanding it conceptually as a landscape and an ecology unto itself. “Cottonwoods” stand as a representation of the endpoint of that section, the river. And understanding the actual cottonwoods as a radically reduced ecosystem—it used to be huge and now it’s this very small, lineal thing.

Along the river?

Yes. We wanted to make a civic space that referenced ecology in a way that would be meaningful to people, that was the principal idea. The disciplinary ideas behind it— I mean sculpturally it’s definitely a reference to Richard Serra, his COR-TEN works. I refer to “Cottonwoods” as if a lace maker collaborated with Richard Serra. What could conceivably happen there? We wanted this fine grained, modulated sort of thing to happen. Serra has a tendency to make space in a very aggressive way or to defy space. He’s a critic of architecture and so his sculpture is almost invariably a kind of gesture to architecture.

An offensive gesture, maybe. That’s the passive aggressive design example I was looking for. Serra is our perfect example.

Yes. For “Cottonwoods”, some people may be drawn in by shadow play. Others might be drawn in by scale. Others may be drawn in by the simple sort of space that the seven pieces collectively make. Others might just be indifferent.

I really like the new hardscaping at City Hall, by the way, and I love the lawn with the patio seats!

Yeah, ultimately the city hired a landscape architecture firm, GGLO, and we collaborated with them.

My friend and I were talking about the difficulties of public art. It’s so subjective, right? It’s like trying on clothes, who gets to decide what our city is wearing? And can you make everyone happy?

Yeah, I agree. Public art is a sticky wicket.

Exactly. I just remembered something, earlier, you were talking about dream clients and you specifically mentioned a limited budget. That sounds counterintuitive, wouldn’t a dream project have unlimited resources?

OK, so here’s an example that you likely know: James Turrell, Roden Crater, do you know that project?

You’ll have to describe it.

Turrell always makes these light chambers. Roden Crater is in northern Arizona; basically, he was able to acquire a crater, actually I think it’s a volcanic cone. It’s being funded by the Dia Art Foundation; it’s an unlimited budget. And it’s like, oh man, that’s too bad.

[laughs] Why?

There’s no restraint, the focus is lost. I think an unlimited budget is the worst thing to happen to anyone. Win the lottery, that’s a surefire way to ruin your life. This goes for artists and designers, as well. Win the lottery that way and you’re done. What are you going to do? You’re just going to play for the rest of your life and think every new doodad is an answer to something. The constraints of a budget, the constraints of a site, the constraints of whatever, are absolutely necessary. Otherwise you’re just going to try and make the thing that encompasses everything.

Just, like, way overdoing it?

It’s like a typical mistake for an art student, I’ll use painting because it’s a really clear example to me, a student painter thinks they’re going to make a painting that answers all of the questions of painting. And they’re not satisfied if they’re doing that. It’s like no, no, no; you have to ask one question of painting. Make a painting that grapples with that question.

Do you have a question that you revisit over and over again for your own creative drive?

Good question.

It’s a big one.

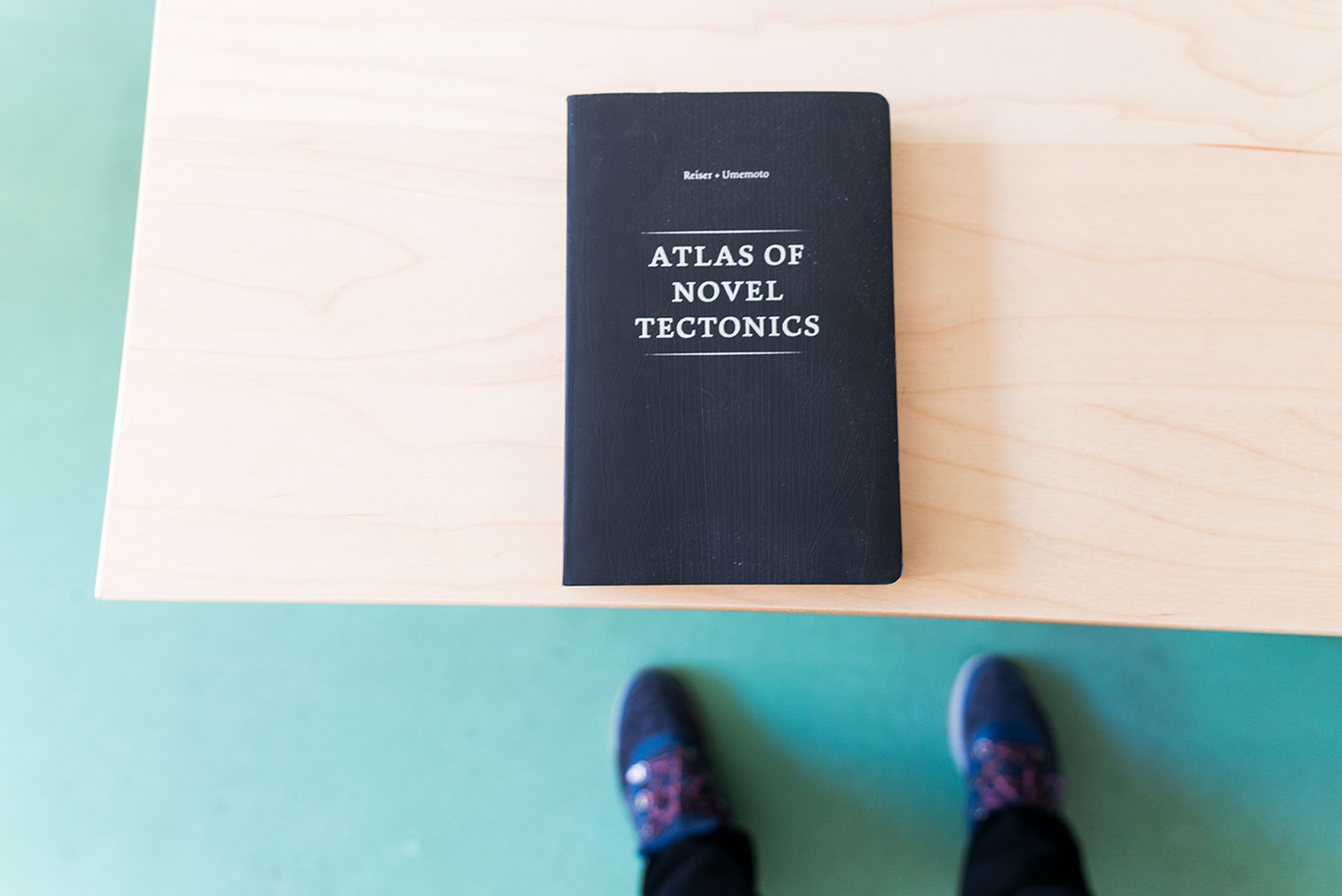

It’s one that I force architecture thesis students to address, ‘What are you asking of the discipline? What’s your question of architecture? Can it do this, or should it, or has it done this?’ Etc. My recurring questions; I think about with regards to art and architecture, reside in— My artistic practices are a stack of 3 x 5 index cards, you know? Where I’m writing down some idea, some thought, sometimes it’s like, oh my god that’s a 20-year project; this is a huge idea you would have to commit to, and it’s what you would be doing for the rest of your life. That thing that’s written on that card. And then there’s another card that says ‘make a series of drawings that combine geometric projection with gesture.’ Both of those things are questions. The 20-year project is to do an investigation of the presence of architecture in cinema and make a searchable database—

That’s huge! It could be real architecture, if a film was shot on location, or it could be imagined architecture designed for the purpose of storytelling.

It would be so beautiful to make database that catalogs every significant architecture in film. There’s a lot on that subject that I think is worthy of scholarship. No one has really scratched the surface on how filmmakers use architecture and how architecture enables certain kinds of film. So that’s a question that I have.

It could be a database, a book, a—

Library, archives.

It is a beautiful idea. Let’s talk more about your stack of index cards.

[Laughs]

Do you feel a tug between creating the things to write on the cards versus the satisfaction of actually doing one?

Some ideas, as soon as I’ve thought of the idea, it’s done in a way. Like as soon as I write it down on a card, that’s good enough, it’s just a thought. And maybe it gets formalized with a couple of words. Others really have to be done to be an actual idea; that thing isn’t really an idea that’s being written down, it’s a directive for work. You have to execute it, in order for it to be an idea.

I’m struggling with that. What do you mean; it’s not an idea until you make it? Isn’t the fact you described it to me, isn’t that an idea?

It is. I’m trying to double down on the necessity of making. Yeah, it’s conceptually driven, but the concept is inert until it’s in action.

It needs to be acted upon. I would really like to look at this stack of cards.

Mmm. I’ll show you. No, no. It’s better in your imagination.

How tall is it?

It’s concise. It’s like that tall.

Do you have any drawings in there?

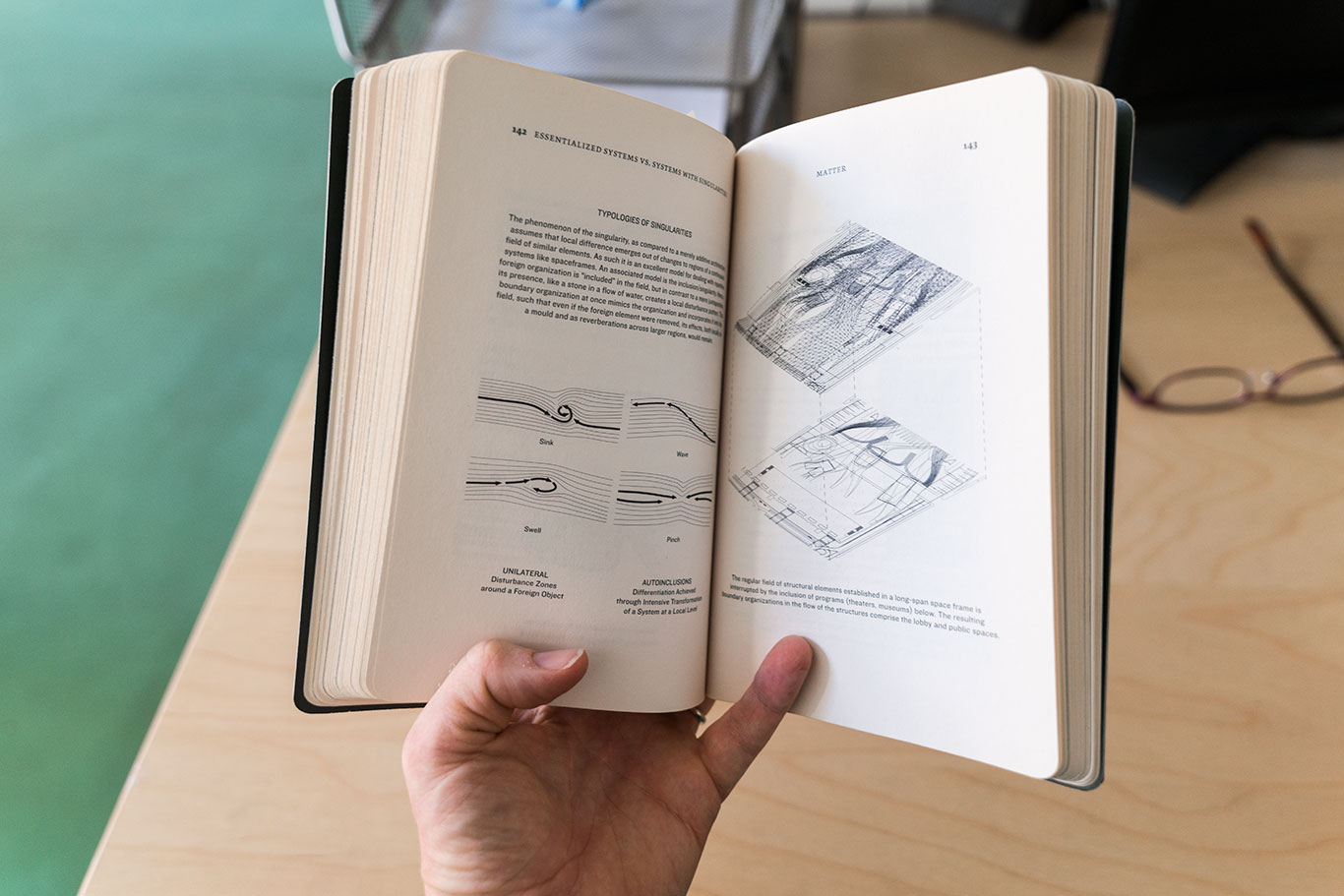

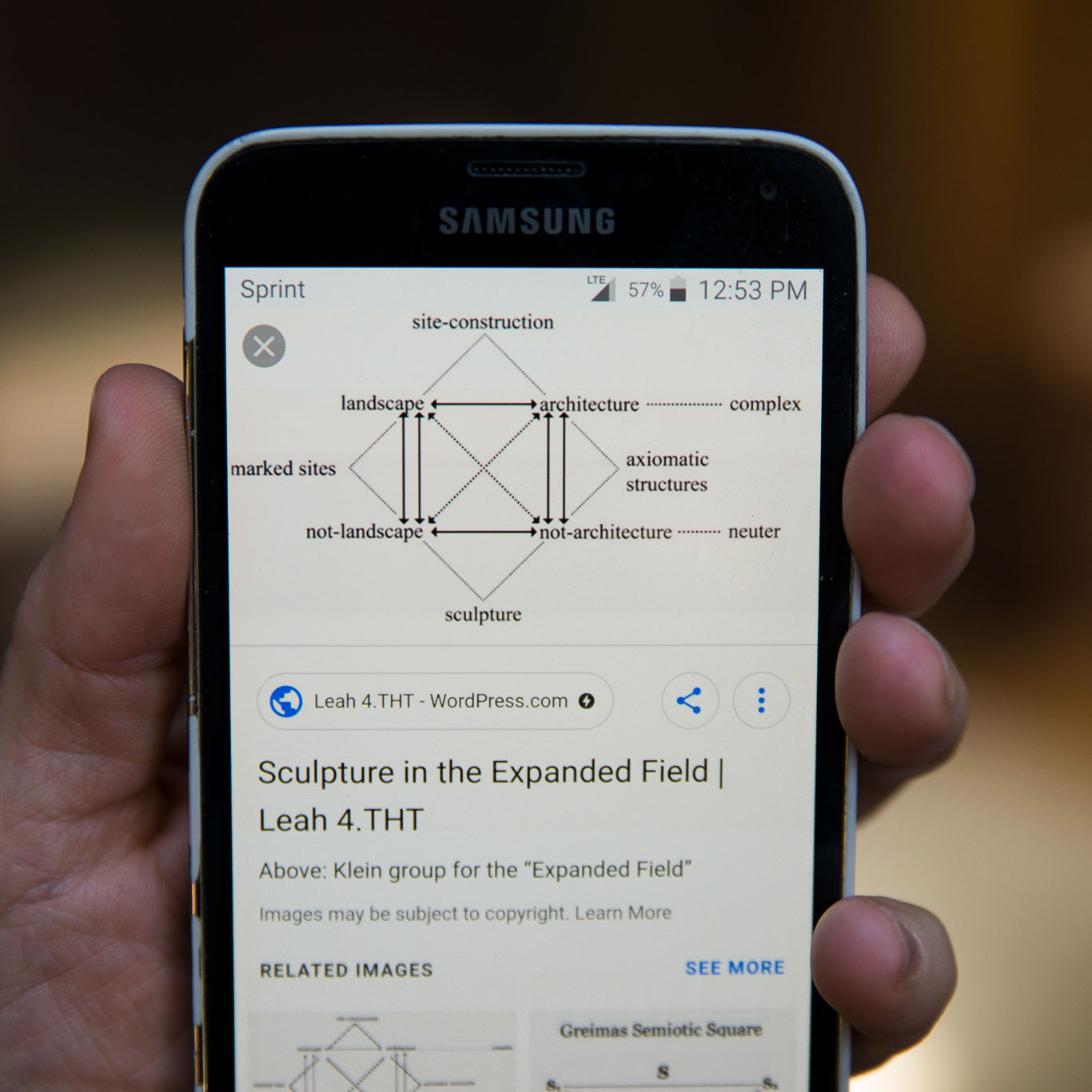

Well, I ran across this image the other day. Alex, my son who is also an artist, and I were having a conversation late at night at the kitchen counter. We were trying to map the theoretical framework of art in general over a larger history. We were using Rosalind Krauss’ ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, that semiotic cube, I don’t know if you know it. She takes architecture/not architecture, landscape/not landscape and uses a semiotic procedure in order to find the expanded field of sculpture, and comes up with earthwork, Etc. Anyway, using that semiotic model of binary oppositions we were talking about art and design. It’s essentially the two binary oppositions that we depart from and sort of map out everybody’s artistic practice and architectural practice from that and make them all conform to it. It’s utopian/dystopian and autonomy/contingent that map out the four squares that you can vectorize. It works like a grid.

So you’re making a graph. [Note: Rosalind Krauss’ ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’ uses a Klein 4 diagram; I have since looked up the Klein 4 and discovered it is a mathematical concept that is much more complex than a graph and has similarities to a Venn diagram, but with additional functions and it looks cool.] You two worked on that out of sheer curiosity, I bet. And of course for the pleasure of organizing all these axes you’re interested in and placing them in relation to each other.

Yeah, just like how you would organize a chronological timeline.

I feel like we need a little bit of fluff in here….Before we wrap up, I have to ask, did you know there is a website called Rate my Professor? And you’ve got one review from Boise State: ‘Excellent professor. Very knowledgeable and personable. His extensive vocabulary can intimidate some but he will ‘dumb it down’ upon request. Highly recommended.’

That’s pretty good.

Yes it is.

Central Bench

November 7, 2018

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.