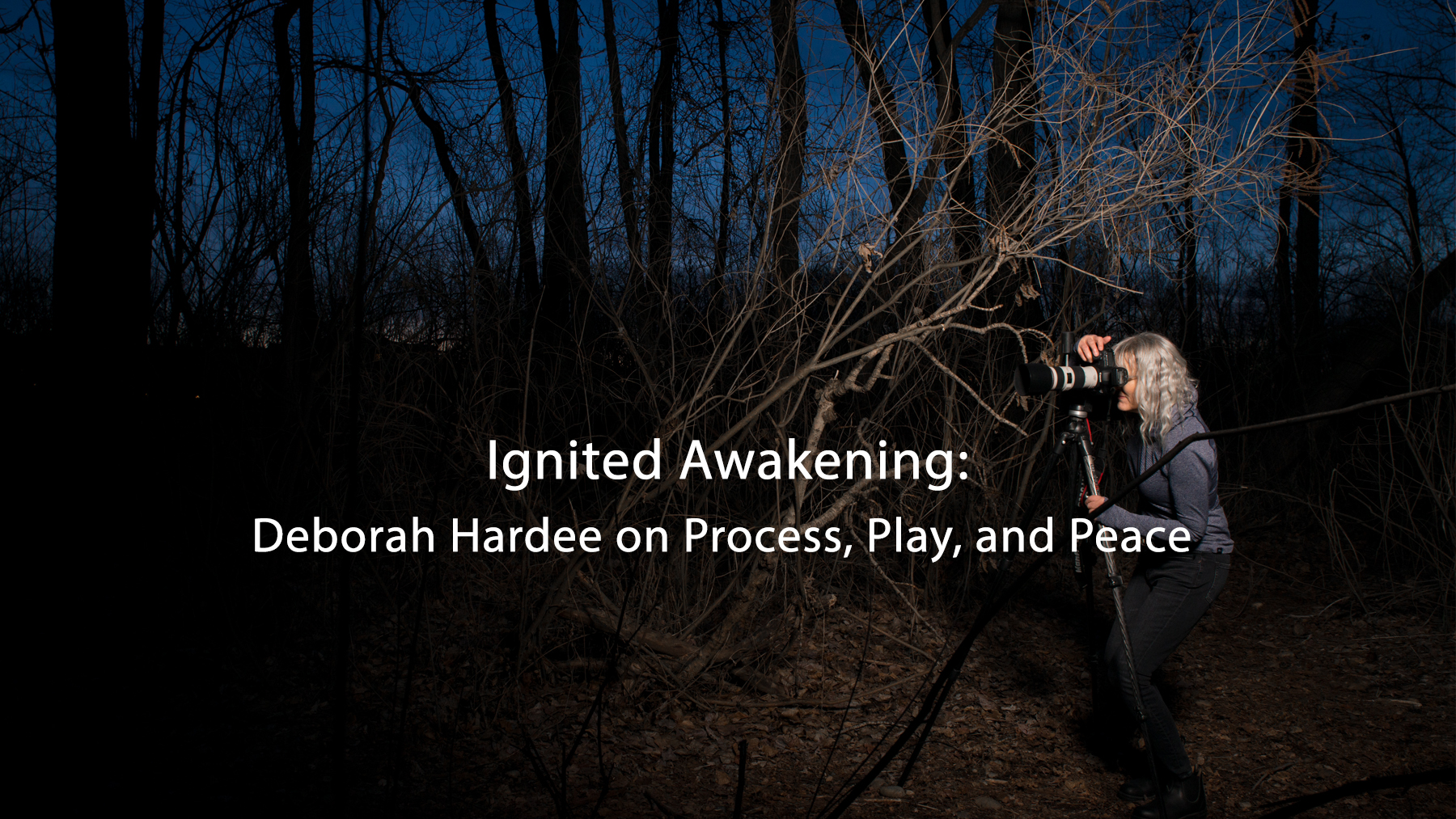

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Deborah Hardee

Posted on 9/25/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Deborah Hardee is a photographer working on both personal and commercial projects, bringing her unique aesthetic and emphasis on unrestrained creativity, play, and collaboration to all of them. Having built a strong brand for herself in a historically male-dominated field, she describes rejecting multiple jobs that required her to accept less pay, opportunity, and recognition. With a soft-spoken presence, Deborah tells us about a kind of fabric: of work, awakening, and art, all woven together in harmony. She says it’s about learning from mistakes, showing up with an adventurous spirit, and designing a life where what you choose to leave out is just as important as what you choose to leave in. The results are magical, and it shows.

I was able to come out and document you on a shoot; I was photographing you photographing a model (Parker Boles.) But because I am familiar with your work, and I am a big fan, by the way, I was incredibly nervous. So nervous that I think I mentally blacked out at one point. [laughter] Have you ever felt like that?

Oh, yes. In fact I gave a lecture a couple of years ago to the Boise Graphic Design Group and American Society of Media Photographers about the Imposter Syndrome. I think we all have that voice inside that says we’re not good enough. “We shouldn’t really be doing this. Who do we think we are? What credentials do we have to show up like this?” Instead of feeling free to play with each other. You know, just un-abandoned creativity and play.

Without watching the self and being critical?

Right. We have an inner child that is wounded, and a feeling that we are fundamentally flawed somehow. When I first started working, I would stay up all night worrying. I don’t need to do that anymore, and yet, there is always a sense of caution, especially working for a client who needs a certain outcome. You have to bring that creativity with you and that sense of [unhindered] collaboration.

Does that give you more freedom to follow an impulse?

Yes. But at the same time, it’s good to know what your bias is. Sometimes in the past I thought I’ve known what the client wants, when it’s not what they needed. I think that voice is valid as well, not in that you’re an imposter, but as a caution to really show up for the client.

To show up prepared, mentally and physically?

Right. I’m really into preproduction. That really takes the worry down some.

What kind of preproduction?

Location scouting, getting the right crew together, making sure that the client hires a makeup artist— unless they can’t afford it, which is sometimes the case. But usually I can talk them into it because having the right crew, the right wardrobe, and really thinking through the [specifics] and communicating with the talent is important. For example, I can’t tell you how many professional models show up unprepared, their clothes are stuffed in a bag and wadded up.

Wrinkly?

Yes, wrinkly. Or, I tell them, “Look, your hands are going to be in the shot, so make sure you get a manicure.” But that’s not on their radar, or they didn’t read that sentence. So you make sure the makeup artist knows she might be doing a manicure as well. A lot of details go into the making of an image, so you’ve got to think those things through to really show up. I just did an advertising shoot photographing a family—“What kind of mood are we going for?” I toured the location, I found comps and sent those to the client so they could say, “Yes” or “No” about our direction. I like to do as much of that kind of work as possible in advance.

What is your routine like?

When I have a job, that’s when I work.

So it’s irregular?

Yes. It’s not every day I have a job. Right now I’ve just finished up with a bunch of clients. Then I have a month where I don’t know what I will be doing. I use that free time to plan my own self-motivated shoots, marketing, or business aspects.

Speaking of when you have a stack of jobs: you’ve got the preproduction work, the actual shoot, and postproduction. Which part of the process you like the best? And which part do you hate?

Oh, shooting. And, I don’t hate any of it.

I guess hate is a pretty strong word. [laughter] For the longest time, you have been one of very few women commercial photographers in Boise. Does that kind of independence run in your family?

My father worked for himself, an entrepreneur, a builder, a plasterer. There were always architectural plans around the house. He and my mother would bid on jobs together. He worked on the Beverly Hills Hotel where we were living in Los Angeles, so we’d drive by and he’d say “Look at those walls right there. That’s what I did.” He was a very funny, gregarious person, he was just fun to be around and always pointing out architecture to me.

Did your parents support your creativity?

My twin sister and I were the last of six kids and I think because of that, our parents told us we could study whatever we wanted in college. I was always attracted to the arts and creativity and play. My first semester in college, I took 100% art classes.

That must have been fun. Like eating dessert first.

I had known since a young age that I wanted to be an artist.

You graduated from Boise State and then started working right away?

Yes, my first job was for the Idaho Statesman as a lab technician.

In the darkroom?

Sometimes I would shoot for them as well, if someone came in for a portrait, or sometimes they sent me out on assignment; if there was an emergency, a breaking news story and no one else was around, they would send me.

If who else wasn’t around?

The other, male, photographers.

Interesting.

So I learned speed. I learned to be more aggressive. I learned not to be so shy, not to be so gullible.

Working in the fine arts, you probably spent hours, or days on making a single print in the darkroom. So the newspaper was totally different.

I had a great boss, David Tinney. After a year, they gave me a dime raise and said, you know, that I was lucky to get it. I thought, “I don’t think this is for me.” My father was the type to say “Tell them to take this job and shove it.” I don’t know, can you repeat that?

Oh, we will repeat it.

He had a “Take this job and shove it” mentality. More than “You need to get a job and keep it.” So I went traveling. I lived in San Francisco, Sun Valley for a while. I went to the Maharishi International University for a semester in Fairfield, Iowa. I was a transcendental meditator all through college.

A transcendental meditator? We will have to talk about that.

Yes, also in Iowa I worked for a commercial photographer. While he was away traveling, he was hired to do a shoot, he had left me to take care of his business. So I did this shoot for him—

You took care of the client from start to finish?

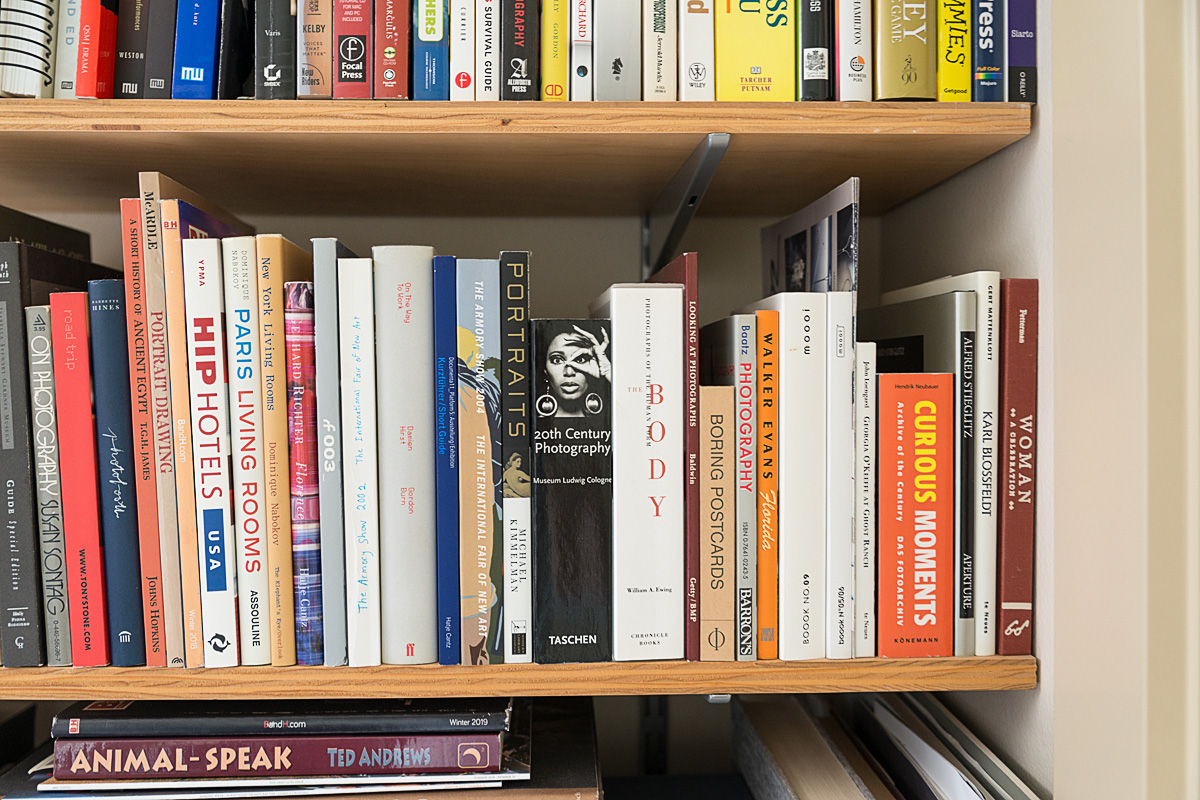

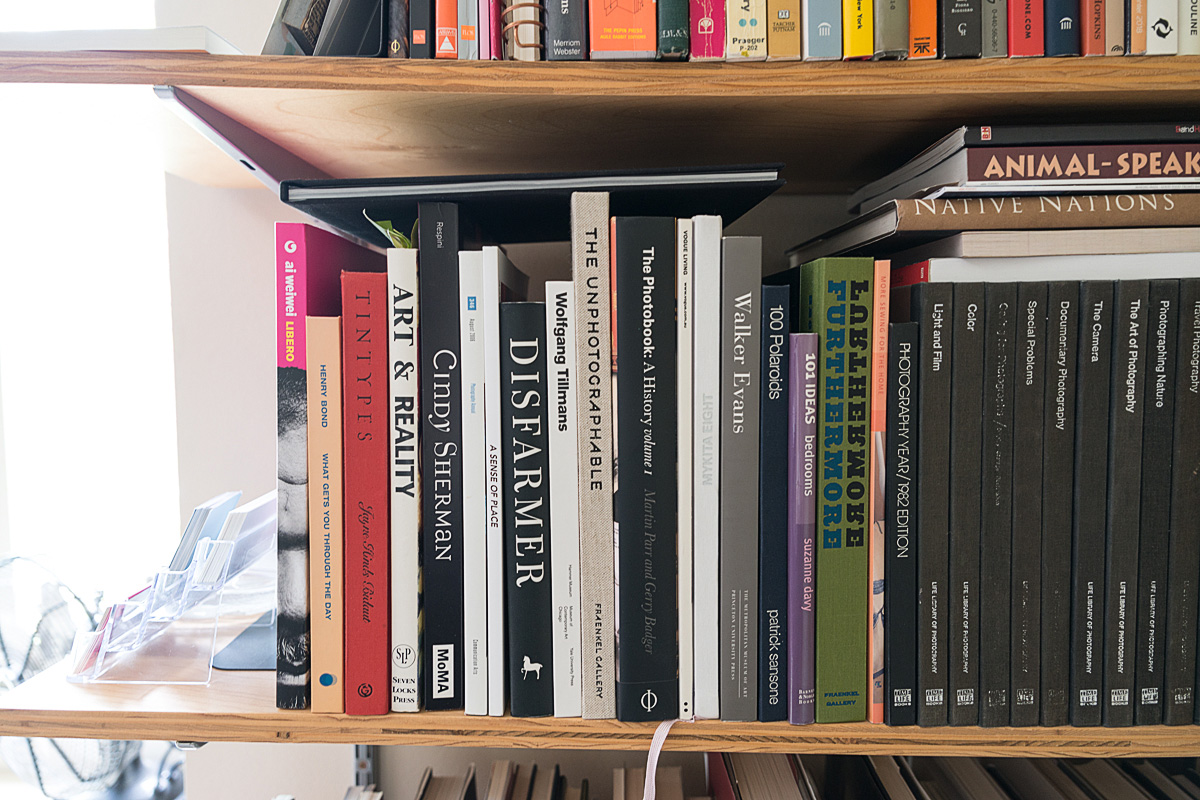

I did the whole thing. I made $32 and he made $500. I thought, “There’s something wrong with this picture.” From there I moved to Phoenix. I lived there the longest, I loved living in the desert. It’s really exotic, and not so [populated] as it is now. That’s where I really decided to become a commercial photographer. I was looking at photographers like Avedon, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, just a lot of those photographers from the 40s, 30s, 50s. Karsh. I was familiar with the kind of work they were doing in portrait, yet they also had assignments. I liked that idea because it was more fine art orientated than straight up retail.

An assignment gives you a framework within to express your creativity.

My degree is in fine art—painting—and I had a year as a photo journalist, but everything else I’ve learned while working commercially, which is a lot.

Learning on the job?

Yes, from other photographers, art directors. It’s a series of little mistakes that you’ve got to overcome. Little corrections: “Lift the chin” or “Whoops, I’ve been shooting for 15 frames and I haven’t even checked my exposure.” You know, I just picked up my camera and started shooting, which is a typical mistake I make. I get so inspired by what’s in front of me that I don’t even think about the technology.

You worked a lot in black and white and you work mostly in color now. Do you have a preference?

No. I love black and white. It’s just I don’t think about it as much anymore. When you were shooting film, you really had to decide: Am I going to put black and white film in the camera or am I going to put color in?

That doesn’t matter now.

It’s irrelevant. But, I just think in color. Occasionally, I get a shot, and, “Oh, this would look great in black and white.”

Sometimes you can just see it. It just jumps out at you, the light and shadow. I want to know what the Maharishi University was like!

There were two meditation domes and everyone there meditated. Women would go in one dome and men would go in the other.

For how long?

Well, we did breathing—pranayama—before we meditated. Then we rested after we meditated. So, up to an hour and a half.

On a daily basis?

Morning and night.

Oh, twice a day.

Twice a day. And then classes. Every class was taught with quantum physics as its basis because Maharishi was a physicist. He taught basically what Einstein taught: it’s oneness. We are all part of a unified field of consciousness.

A fabric of consciousness?

It was really, really fascinating and lovely, and I still have good friends from that community. But it was such a small town, having grown up in LA, it was just too small for me. How can I be a photographer in a really tiny town?

You’ve lived in a lot of different places, and invented your own path. You must be pretty adventurous?

Absolutely, I have an adventurous spirit. To be a commercial photographer is an adventure. I’ve been able to see so many things and unique circumstances: murder, fancy resorts, beautiful architecture, babies being born, famous musicians, a lot of different businesses.

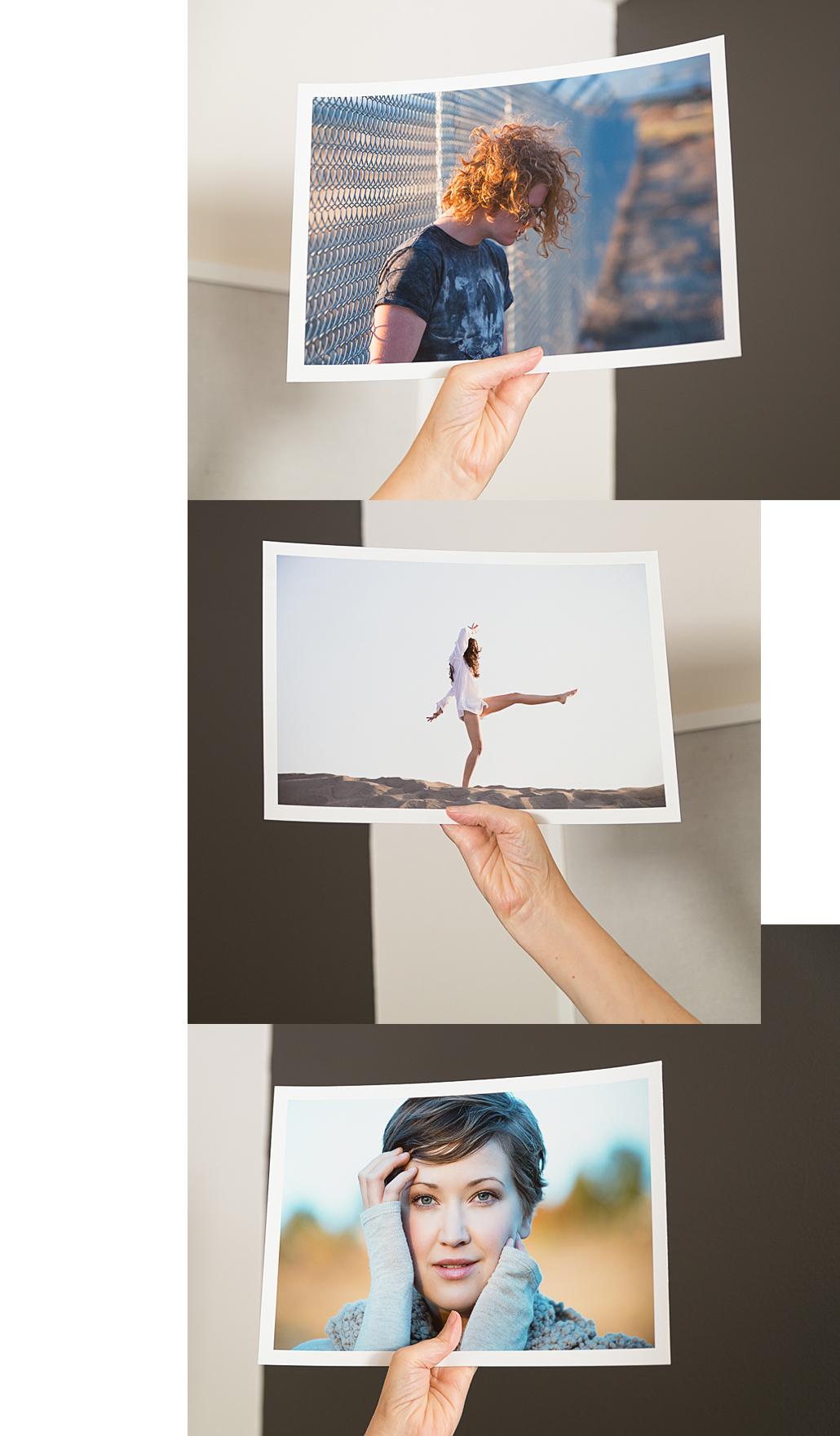

What is your favorite kind of project?

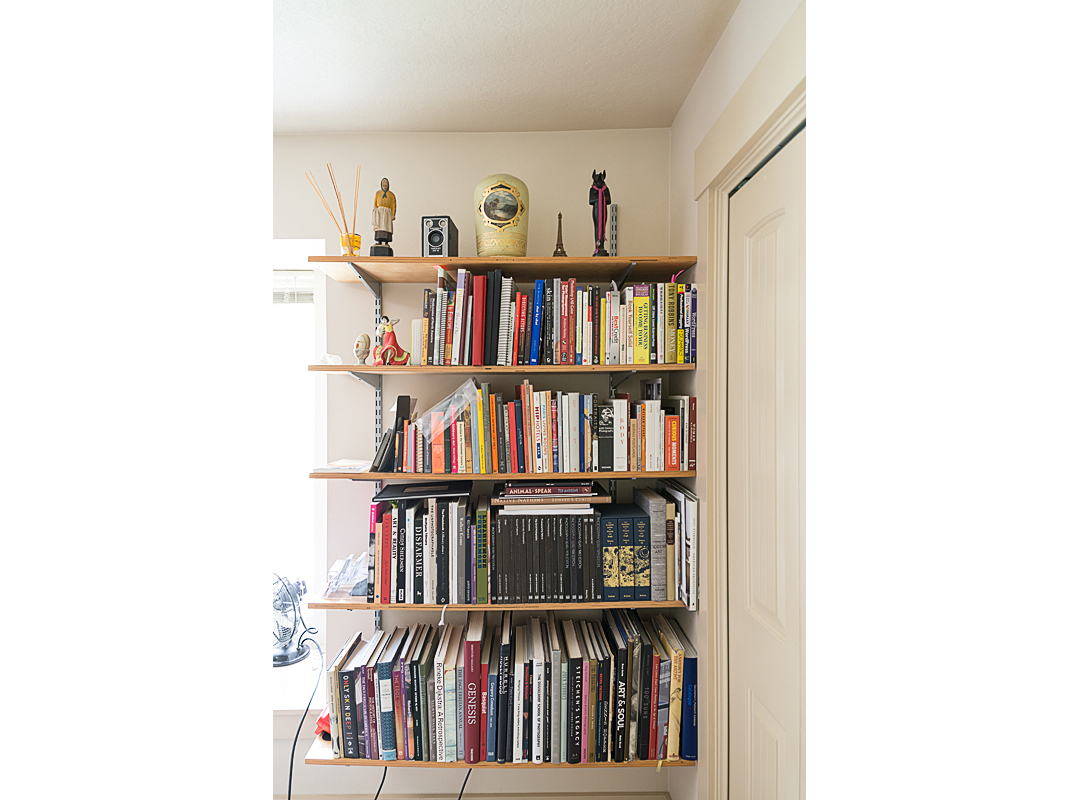

It usually involves a person in a beautiful location, I really love that combination, or even just a straight up studio portrait. Anything you see up on my website is [probably a personal project.] Right now, I’m really interested in making a book of my work, a portfolio book.

I was trying to describe your aesthetic, because I love it, and I find it very unusual and subtle. I still haven’t figured out exactly how to describe it. I think it has something to do with which images make the final cut after a shoot is over.

I’ve gotten better at editing my own work and I think that comes as you mature as an artist. But collaborating with an awesome editor is a powerful way to inform yourself about your own work, to describe what it is that you do, someone to show you what is the cream of the crop.

So, a portfolio review?

Yes, I had one with Jennifer Kilberg, from Agency Access. I sent her 700 images and she toned it down to [a fraction of that]. Now I’m able to keep that theme going. I don’t need to rely on her as much.

She looked at a huge amount of work and pinpointed where your voice was the strongest?

Exactly. That was really helpful. It’s important if you’re working by yourself a lot. What you leave out is just as important as what you leave in. It’s great to know why to leave certain images out.

That’s a subtle point. How would you describe your aesthetic?

I would call it several things, a love of vintage, or nostalgia. I would say: sensual, feminine, lighthearted, beautiful, sometimes very elegant.

But you also have an edge. While your work might appear light, or moody, or graceful, there’s usually something that is not idealized. For instance your portrait of the man with the red hair with the steely, serious lighting, and he’s got a split lip …

Oh, yeah. It’s a birthmark actually.

From my perspective, not knowing anything about it, I thought he’d gotten in fight or something the week before. It’s unexpected. Just a hint of grit. That, to me, is typical of your aesthetic.

Yeah. I would usually retouch it if it were a temporary blemish, but—no. That’s who he is. He’s known for that mark on his face. I didn’t want to take it off; it brings out his character. I really love the magic that happens when I collaborate with the people I’m photographing.

You have an eye for opportunity?

Just noticing subtle things.

Are you constantly noticing little things like that? At the grocery store or out running errands?

Not necessarily in that environment, but yes, if there’s a person [on the street] who I’d like to photograph. I give them my card, which is a funny component of what I do. I jokingly say that I accost people with my business card. I work a lot with people I’ve met in strange places. Some people just look at me like “You’re a crazy lady and I will have nothing to do with you.” But some people take me up on it.

You approach them with a proposition, to pose for you?

Some of those people are my friends to this day. Sometimes really interesting stories and deep connections happen because I’m willing to make a fool of myself and be vulnerable.

To be vulnerable and make the first move. I’m going back to Transcendental Meditation. What is that?

It’s a meditation technique that helps connect with that absolute feild of all that is. It was such a lovely experience [at the Maharishi University] and it fed my soul. The premise is to reach enlightenment: freedom from being at war with what is happening, and instead, to be in the present moment. After 14 years, I stopped meditating all together, even though I’d been super devoted, because I didn’t know of anyone in the organization, except one or two people, who ever talked about reaching enlightenment. I knew I hadn’t. I was spending up to three hours a day meditating, and I thought, you know, I just want to live my life for a while. I want to be creative. I want to be a photographer. So I’m going to spend my time going for that because I felt like I was so caught up in the spiritual world that I wasn’t developing my business or my career as much as I wanted to.

You wanted to shift your focus?

Right. So I stopped meditating. But in 2006 something magical began happening. I was actually unloading the car and a blissful feeling came over me without having meditated or—I hadn’t been doing anything for years, but the seeds had been planted. Over the next six years, that feeling would come and sometimes it would stay for three or five minutes.

Oh, wow.

In India, they call it the experience of Samadhi. It was as if the work I had done [previously] was a strong igniting of awakening.

Samadhi.

Samadhi. It’s like the best chocolate. It’s like butter. Even though I don’t eat butter anymore.

I’m sorry about the butter.

[laughs] But, there were no human words to describe the feeling I was experiencing. As the years went by, it would come on so strongly that I couldn’t tell when it faded except that, like a month later, it would happen again.

You noticed that it had faded only when it returned stronger? Do you feel that without consciously trying, you may have reached a form of enlightenment?

Yeah. In 2009, I got involved with Oneness. It’s another meditation and blessing technique based in India. A lot of people who are experiencing awakening states of consciousness don’t always have a feeling like that. They just realize that their life is completely different, compared to when they were suffering. I had friends that were always struggling, then it was like they just, broke free.

That is so cool.

They weren’t suffering as intensely anymore. Things were happening in their lives that were synchronistically beautiful experiences.

A flip from a negative space to a positive space? Almost like a magnet, when it realigns itself due to a negative or positive field.

Sometimes it was like night and day.

Has that changed how you work?

Absolutely. I’m not worried about where the next job will come from anymore. I used to worry a lot about that. It’s the classic starving artist thing, a mindset. It’s rampant in our culture, in a way.

The urgency to make opportunity anywhere you can? That can be nerve-wracking.

Trying to force it to happen. This is different, this is knowing that you’re going to attract the opportunity and you don’t have to do anything. Granted, I am working on my website and marketing myself, doing all those things, but it’s not with as much angst.

Angst, fear?

Or fear. Because you are at peace with whatever is happening, like, “Oh, now is my time to plant the garden and clean the house and do more dishes and make my husband a beautiful meal, and go upstairs and make an Instagram post” and, you know, take care of all the things.

The belief that there is a time and place for everything and that you are doing the right thing in the right place at the right time?

I love what I do so much and I often have to pinch myself. It’s like, holy sh*t. I can’t believe I was brave enough to start a business; I knew very few women who independently created their own businesses. I’ve kind of woken up to realizing I’ve really built this incredible life for myself. And I love it.

North End

September 25, 2019

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.