Creators, Makers, & Doers: Geoffrey Krueger

Posted on 11/30/19 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

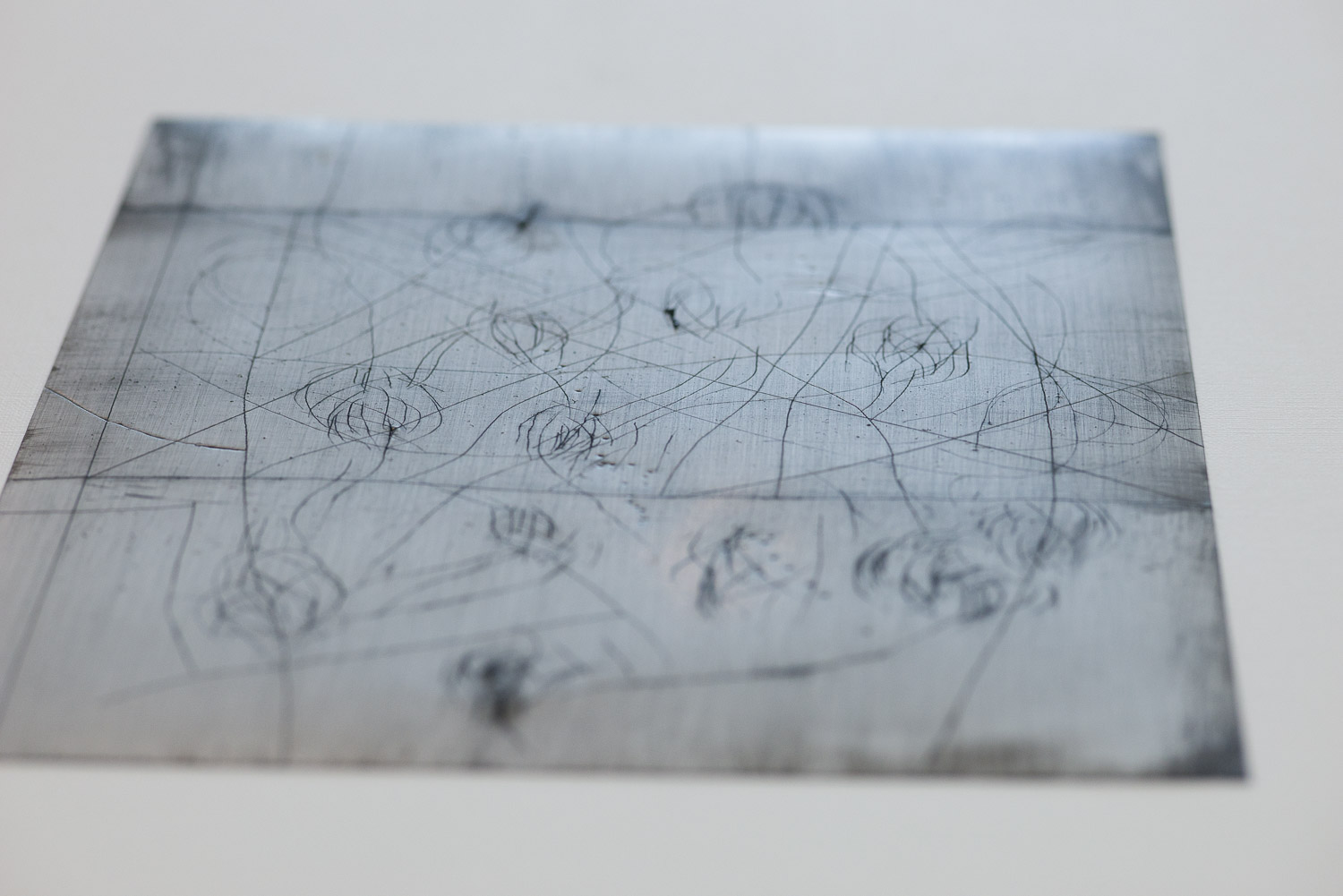

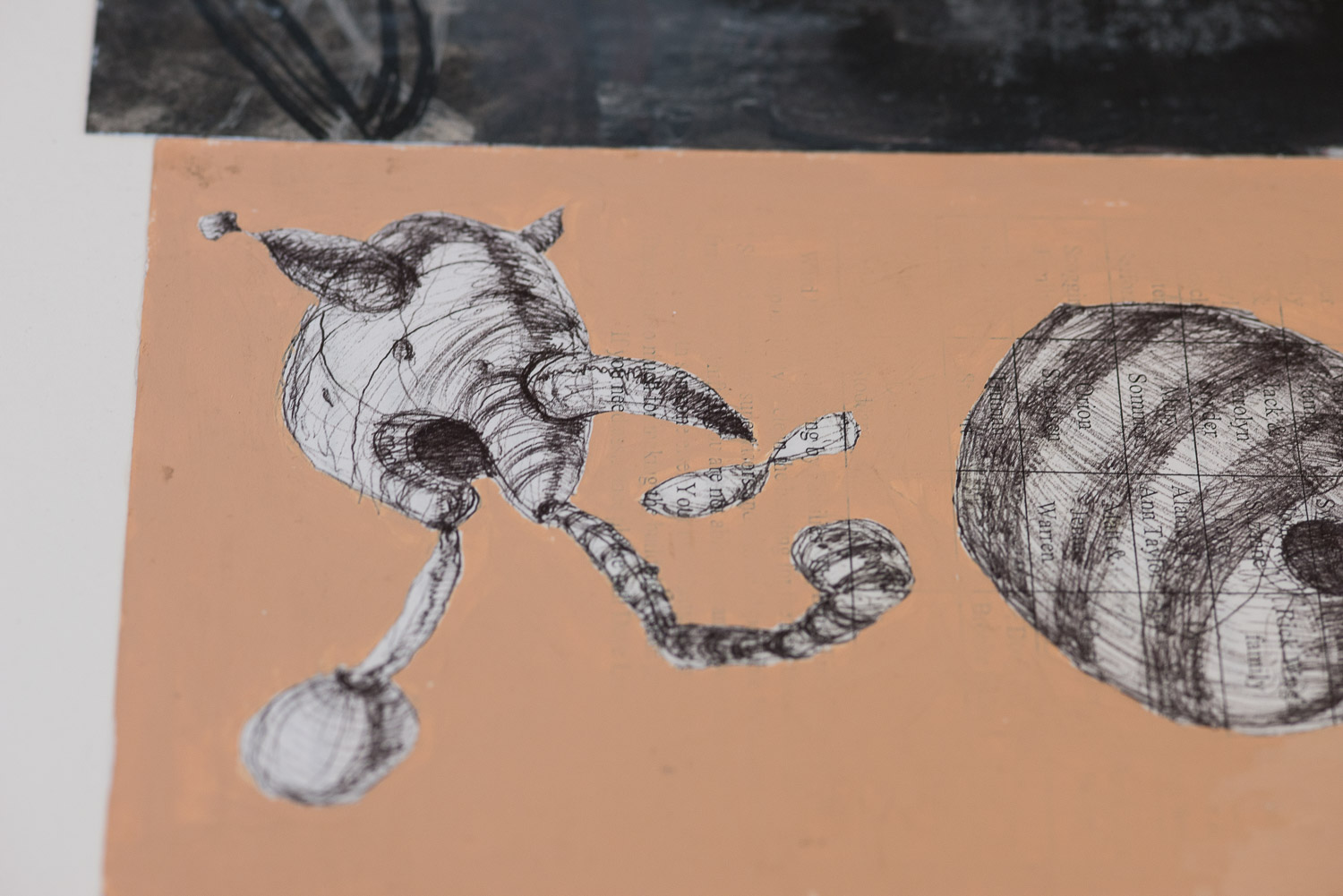

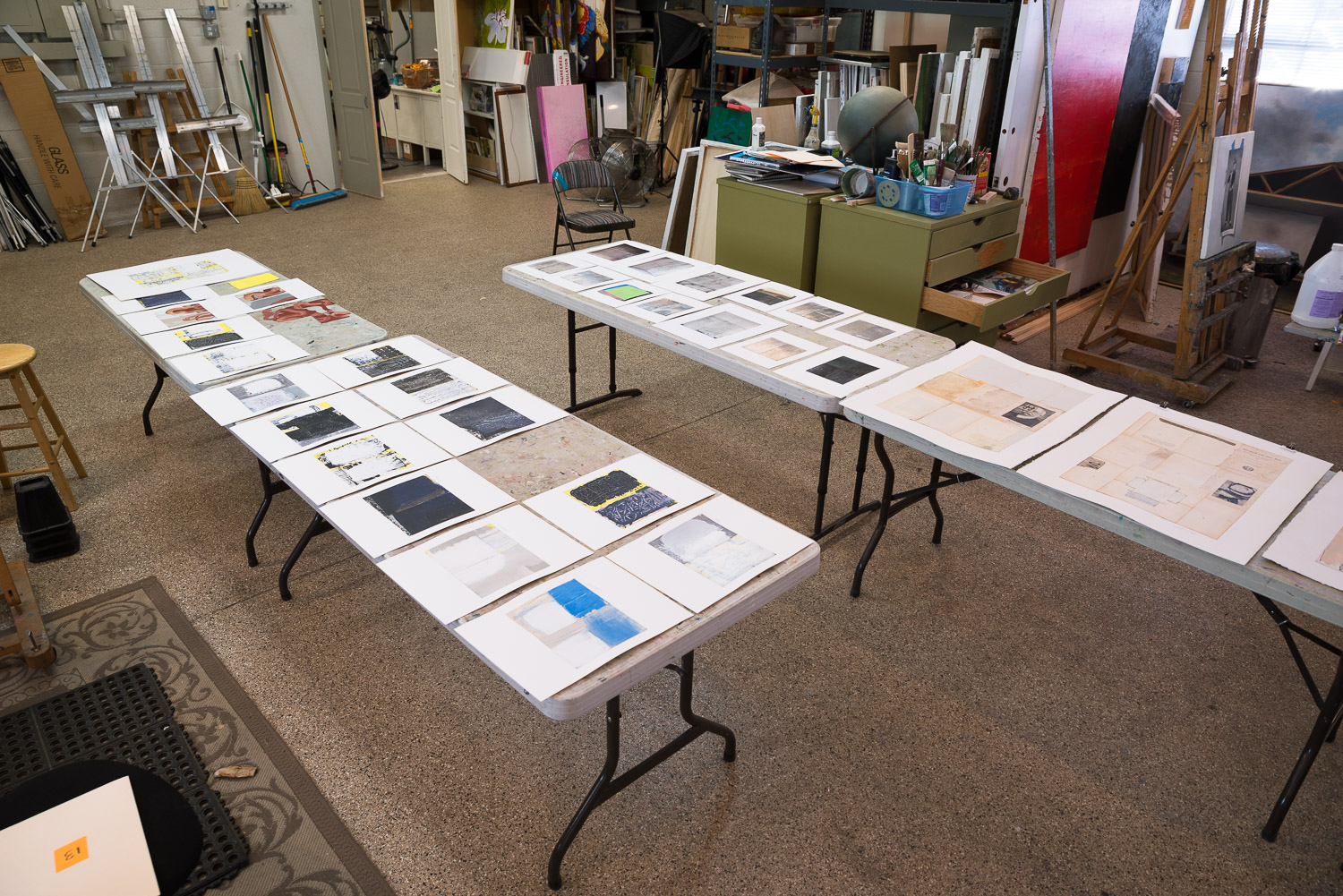

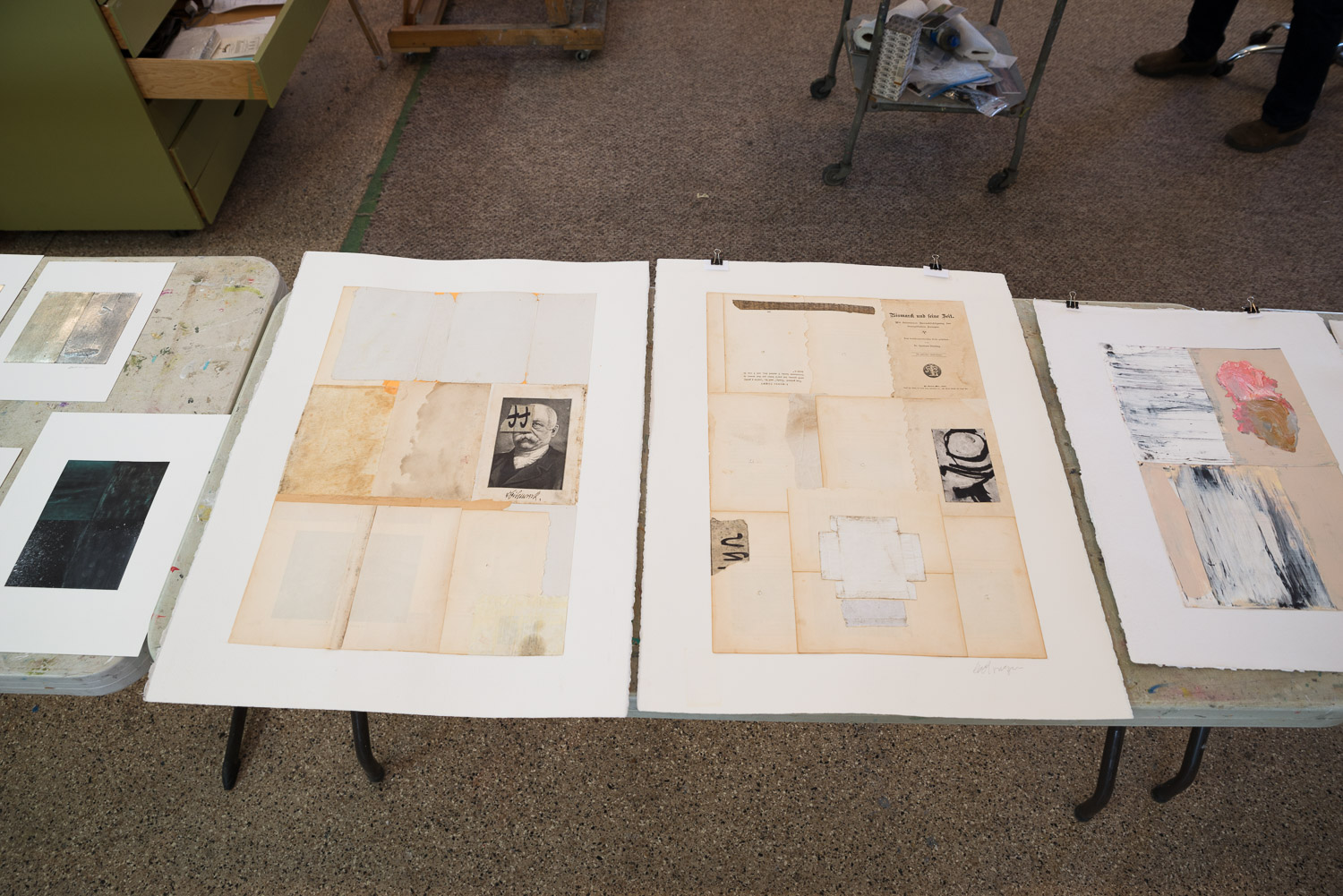

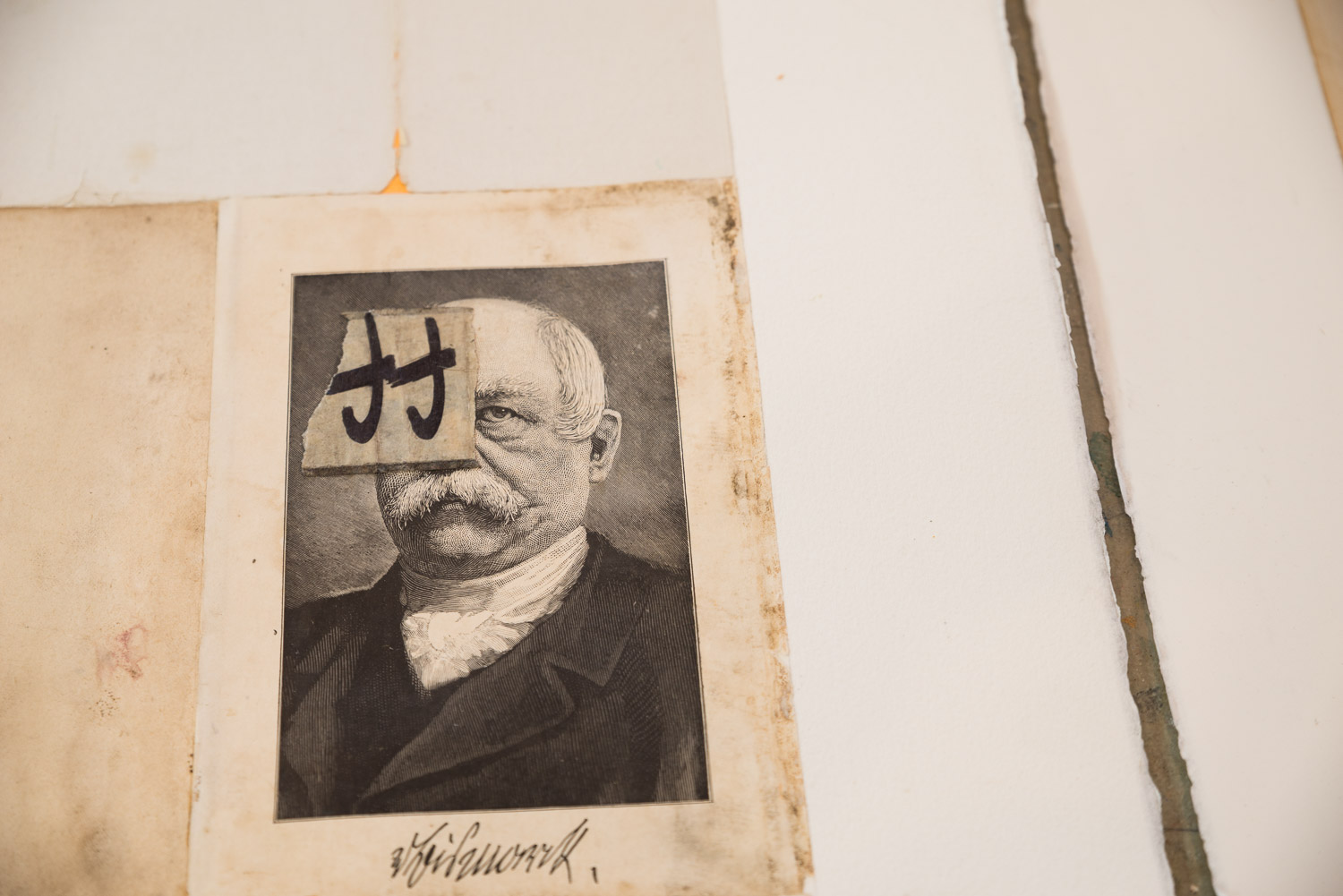

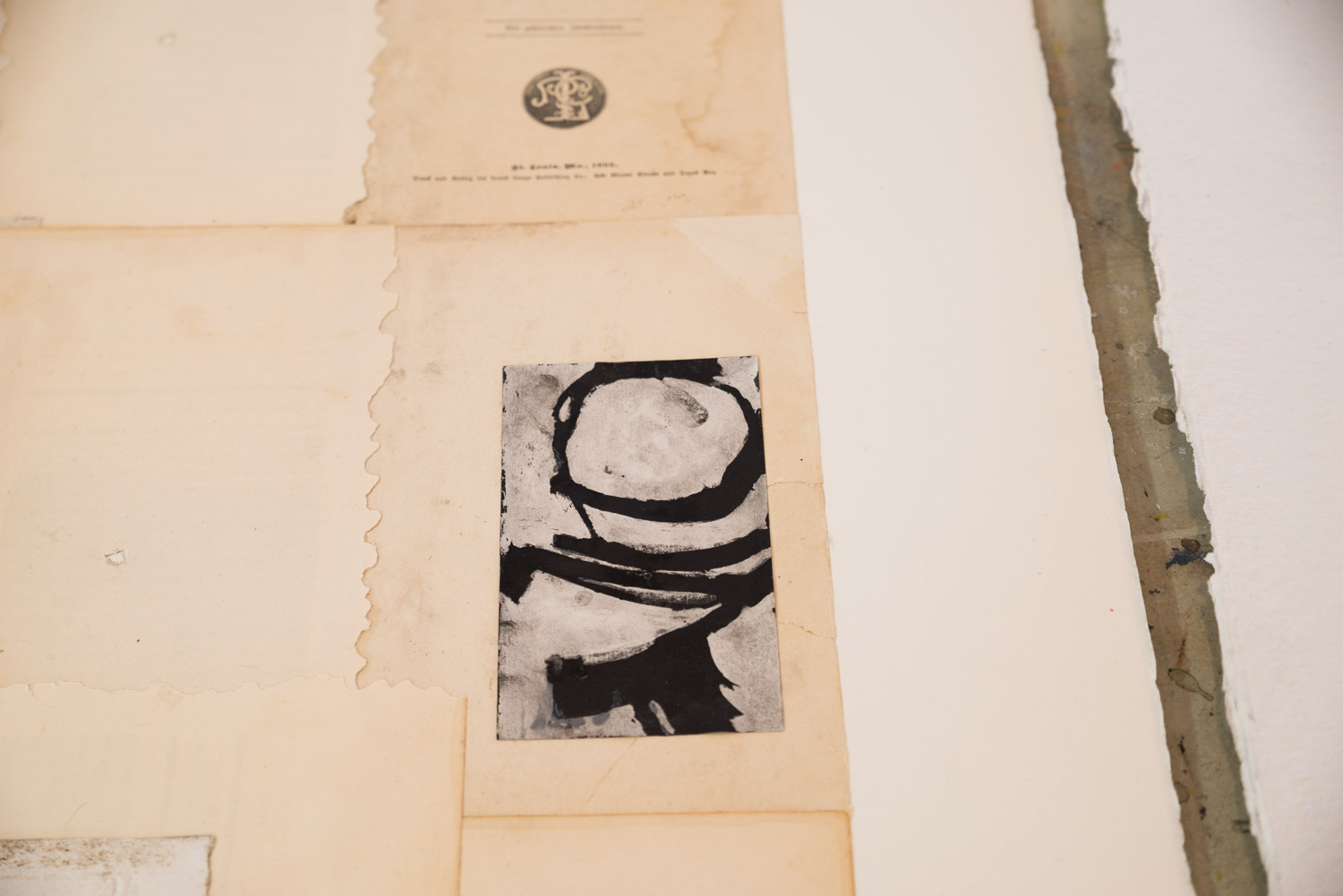

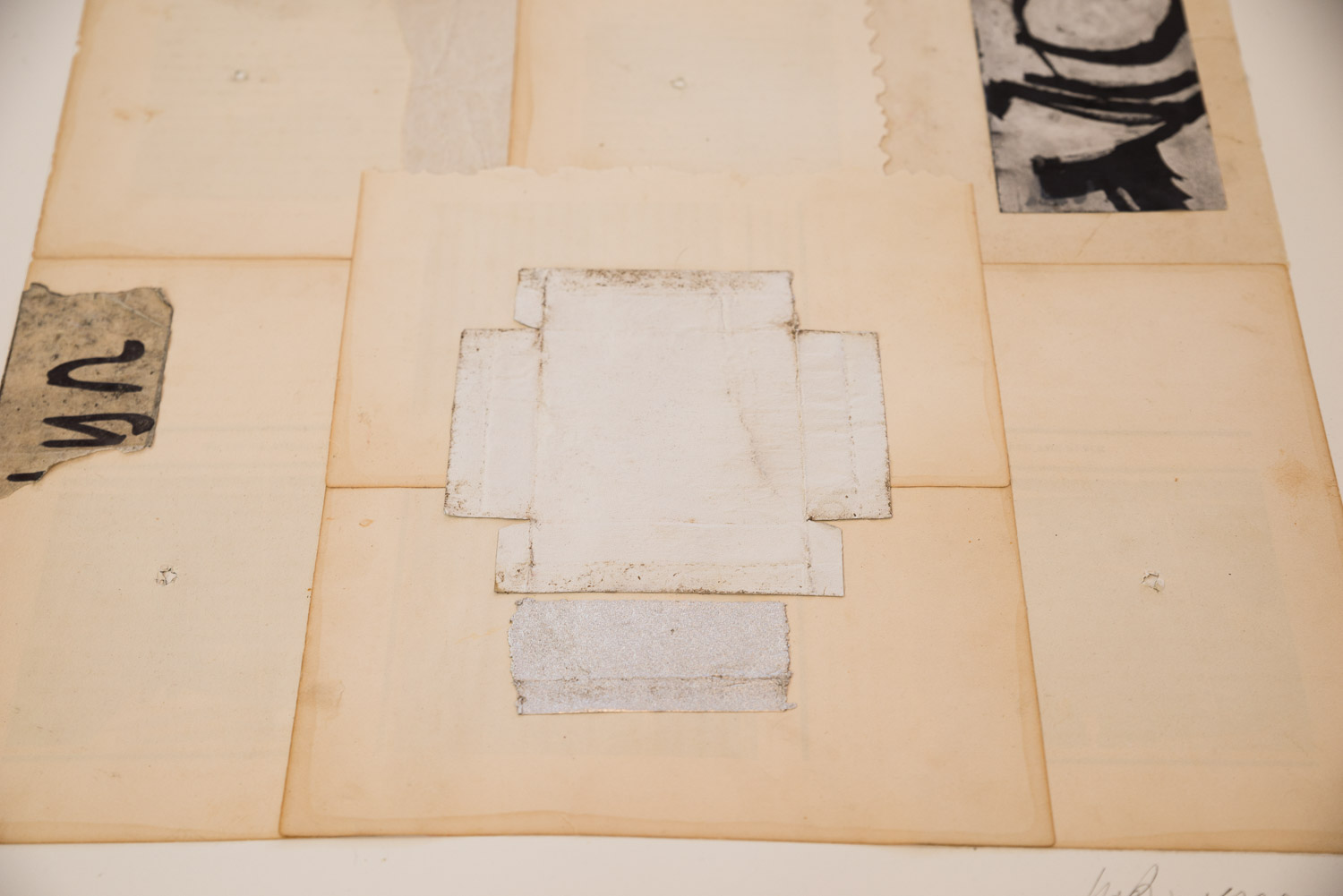

Geoffrey Krueger is an artist and painter who shares a studio space in Garden City with three other artists: Karen Woods, Gina Phillips, and Linda Williams. We sat down with Geoff for an afternoon, looking over his newest work: abstract pieces using found paper and cardboard. He describes a shift away from “painting in a selling way” towards following the joy of exploration without rules and limitations. Geoff works consistently in the studio 5 days a week, 8 hours a day, finding inspiration on Instagram, where he is engaged with other painters around the world—the ones whose work takes his breath away. We chat about everything from the trees of our childhood, our perception of light, color, and shape/form, to the struggles of being an artist: perfectionism, self-doubt, and making a living. Best of all, Geoff shares about a realization: the moment he knew he was meant to be an artist and fulfill an urgency to paint.

You grew up in California?

Yeah, born in 1953. We lived in a really cool, old house. It had a giant backyard, or it seemed giant to me. It had a big avocado tree and a peach tree and a lemon tree.

Did you spend a lot of time in those trees?

I spent probably 80 percent of my time up in that avocado tree. It was where all the neighborhood kids came. We lived there until I was in the fourth grade. There were so many leaves on that tree, no one would know you were up there.

That’s a pretty strong memory.

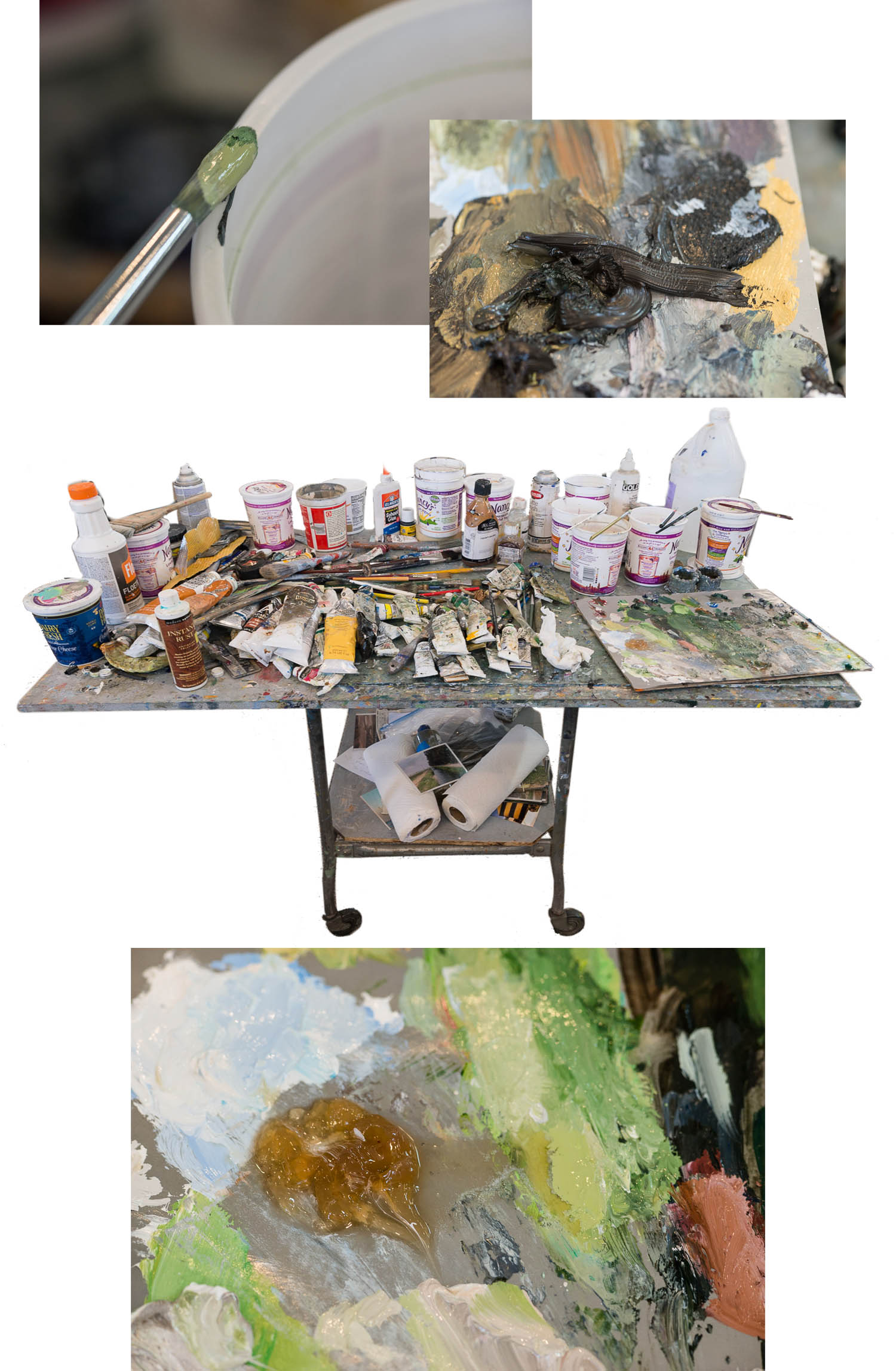

I think it informed a lot of what I do today. In fact, I used to build cities under the avocado tree out of mud and avocado sticks and leaves. Just the other day, I found some really good dirt out in front of the studio. I put it in a pot, and [spread] glue on this board, and poured the dirt on, then painted it. It’s right over there. It’s that black thing hanging on the wall next to the red thing.

Oh, that’s dirt?

Yes, I think I’m finally getting back to what I used to do when I was little, you know, full circle.

What do you mean full circle?

Playing. Not feeling any structure or rules. When I started doing these abstract pieces, I felt like I was going back to an early childhood feeling, of happiness.

Being immersed?

Yeah. That was such a blast. Still is. When I do that kind of work, man, I just, whew, go.

Almost like the work makes itself? When I was a kid I used to sit under a certain tree where the dirt was really soft and powdery. There might have been ants. I’d dig my feet down, because it was warm, facing south. That tactile feeling of dirt, and moving it around, was hypnotic. Moving dirt is like moving paint.

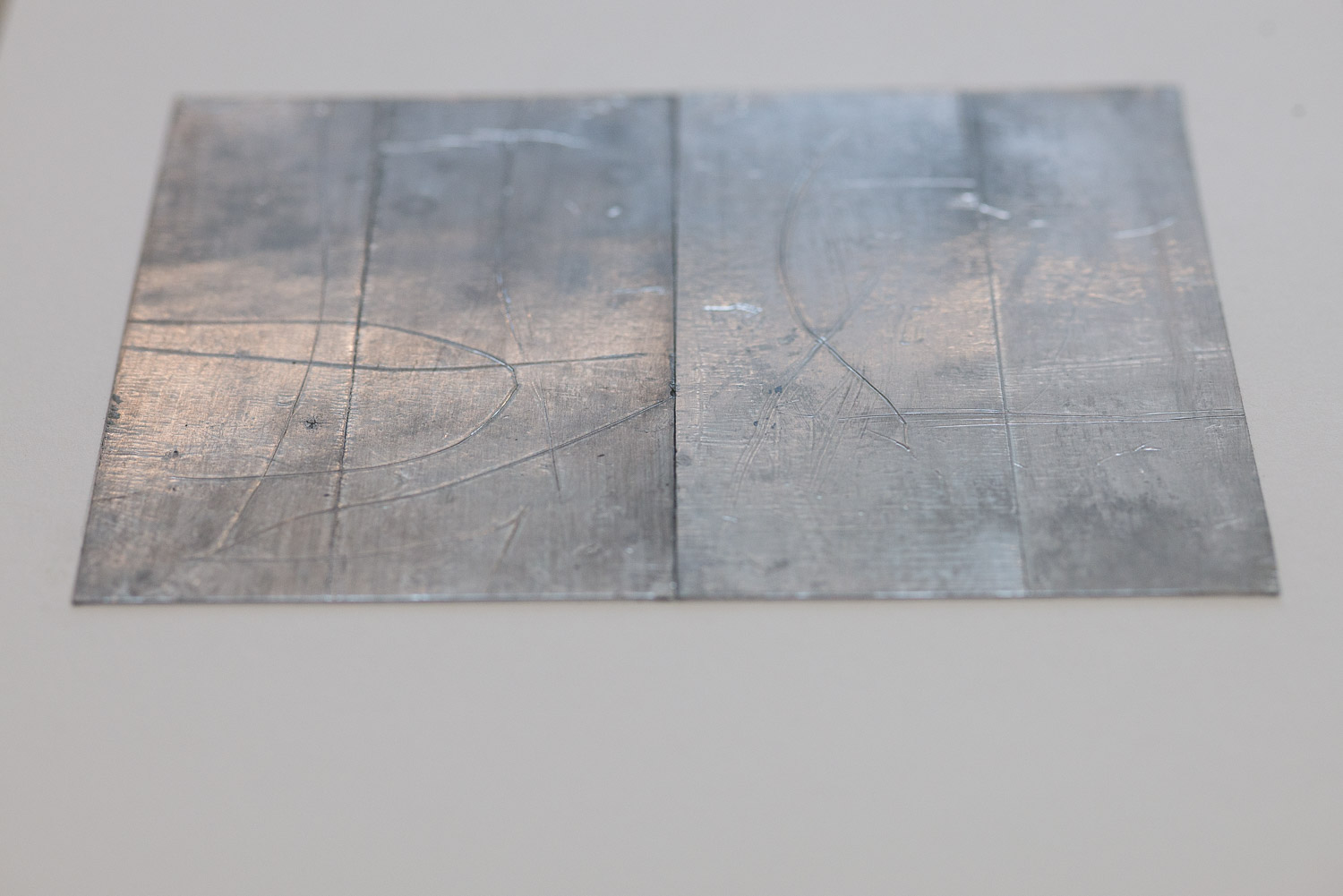

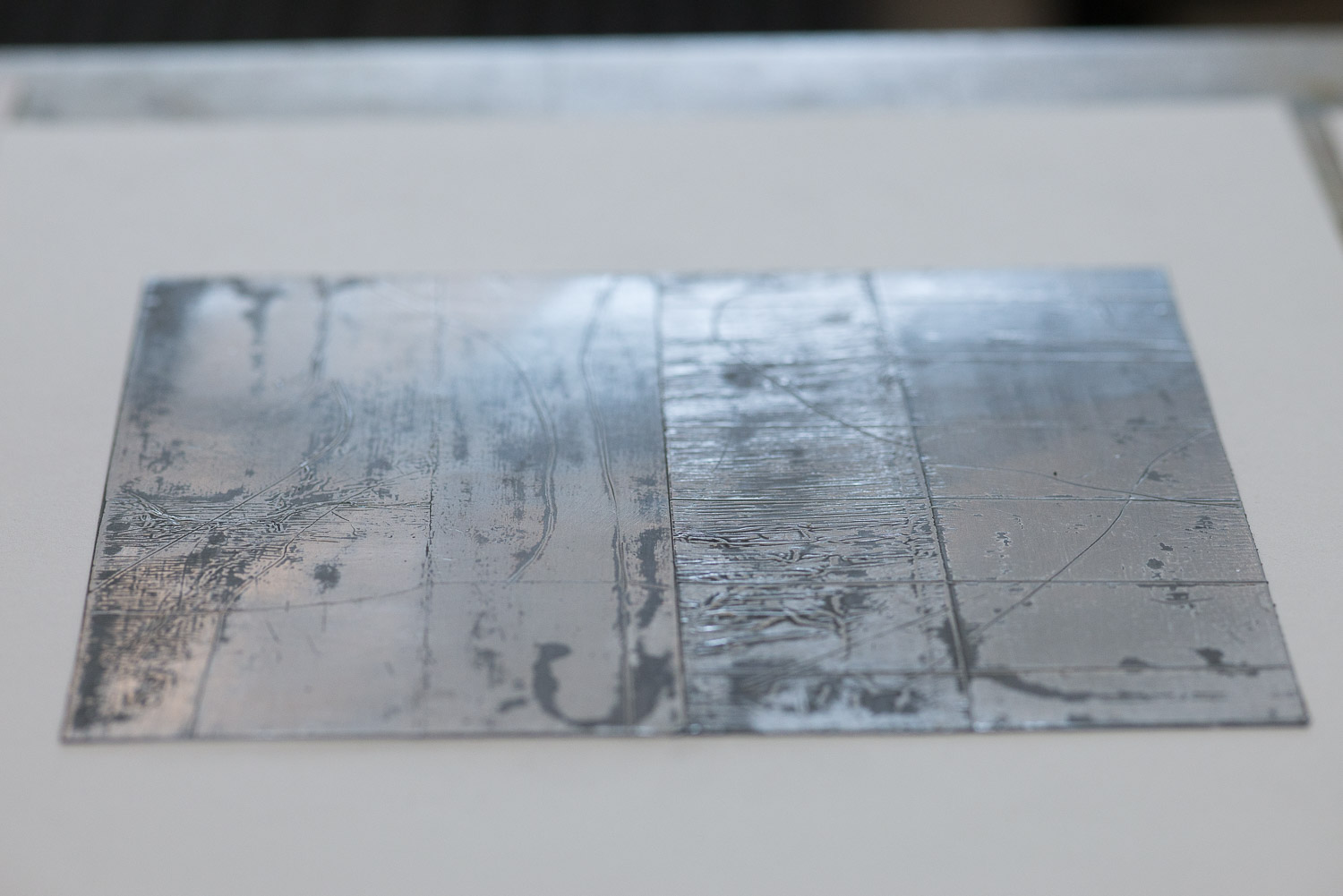

It is. That’s what Charlie Gill calls it, colored mud. Doing this abstract [work] relates to that. When I paint realism, it’s a different mindset. I’m drawn to shapes.

I wouldn’t even say shape. When I think of your work, I think of forms.

I was listening to a song today, Lyle Lovett sang it, called “Step Inside This House.” There’s one lyric that he didn’t write, I can’t remember who wrote it, but it talks about a painting on the wall that isn’t very good, but it looks pretty okay in dim light. I thought, that’s right! That painting carried power because of its shape and the psychological attachment the person had to it.

“It’s pretty okay in dim light,” but not with a bright light. [Laughter] It’s about appreciating an object in a transient state, not the idea of the object as a permanent thing.

And that’s the way you see stuff, right?

No. My mind wants to make it symbolic: I think of a hat, I think of the word hat, and I think of the object without a sense of time or place.

See, I don’t think that way.

That does not surprise me. [Laughter]

I think of it like—I had a really interesting experience the other day, I was looking at a couple of blocks, with the light falling on them, and I forgot it was blocks. I saw it only as light, just for a tiny, little bit of time. Wow, that was weird. The color was separated from the shape. It was a really interesting feeling.

Wow, yeah, I don’t know what that was, but keep doing it!

I don’t know what that was either.

It makes me think of how we might have perceived things as an infant, before language.

Before you could name it.

And you might have just seen just—

Color.

Light. Form.

Yeah.

You were going to say something about another painter here in the studio, Karen [Woods].

When Karen paints, and this happens to me too, your [senses] become heightened to color, and you experience it on the way home. Like yesterday, I got on the freeway, and the colors just opened up. I thought, “Wow, look at that!” It was gorgeous.

You’re spending hours and hours narrowly focused on the limited color palette of your work, and when you get in the car and drive home it is very—

You could almost hear music, you know?

I wish. But, I think I get it. You’re one of the few artists I know who works religiously in the studio, like, you clock in at 8 a.m. and clock out at 5 p.m. What’s your routine like?

I’ve been waking up really early lately; for a while I was going out and taking photographs. Today I got up at 5:00 and looked at Instagram, at art, and thought about things, got down to the studio at 7:30. I had to listen to some music this morning; I don’t always do that, but every once in a while I just need something.

You listen to music to get you into the painting mindset?

No. I needed to get out of the painting mindset.

That’s not what I thought you were going to say.

So I could back away from it a little bit. Sometimes it’s hard to drag myself to the easel and start. I have to sneak up on it. I’ll put up a painting, look at it for a while, then realize, “Oh, that’s what I need to fix.” When the problem’s kind of sticky, I don’t know what to do with it. But if I start working on that area, it will expand out, and I’ll get to the other [work].

So you are painting by 8:30 a.m.

I work in about two and a half hour blocks, then take a break because “I’m tired of this,” or “I’ve solved this problem, now I’m going to start the next one,” but I’ve got to take a break.

What do you do when you take a break?

I pace. Or I sit and look at Instagram or read something. Eat.

What was your first job in the arts?

[Originally] I thought, “I’m going to go into graphic design; that’s what I’m going to do.” I took all my foundation art class assignments from my first year of college, called graphic design studios all over Los Angeles and got some interviews. I was such a naive person, I remember bringing an art director down to my car because I couldn’t carry everything up there. [Laughter]

That’s hilarious.

It is. But I got a job, downtown LA, on the sixth floor. I’d take the bus, walk a couple blocks, hit the elevator, go up, and [sound effect] it would open up right onto the graphic design studio.

You make it so cinematic!

You make it so cinematic!

There was no foyer, it was just [sound effect]. I did some assignments, got paid. When I got back to school, I wasn’t very good at drawing realistically. I felt incompetent and I lost confidence. I [pulled] out of the art program completely and went into communications.

What?

Advertising.

You weren’t skilled at rendering, so you changed majors?

Exactly. It’s more complicated than that, but that’s basically it. I wish somebody would have taken me and gone [slapping sound effect] “Practice!”

Did you need a voice of reason?

Yeah. I was a perfectionist, it had to be perfect or I wasn’t good. I remember graduation day, I was up on stage with the communications college and the fine arts students were graduating in front of us. I watched all those art people walk across the stage and shake hands with the dean, and thought, “What am I doing back here? This is stupid, I shouldn’t be here, I should be up there.”

That makes me sad. You had a moment of clarity.

I did. So after that I went to Fullerton Junior College; they had three art teachers who were unbelievable, they were so good; John Hendricks, Nixson Borah, and Bob Miller. I love those guys, oh, and Marshall Vandruff. I harangued Marshall, “Hey, I want to be an illustrator. How do I get jobs, what do I do?” He lined me up with a couple of art directors, and I started freelance illustration. I did that for five years, taught myself drawing, and practiced different projects; I was getting paid to practice. But I realized, I’m not very good at the business part.

The contracts and deadlines?

No, the deadlines were fine. It was selling myself to get more jobs. Because I didn’t get that art degree, I felt like an interloper, like I was sneaking in the back door.

You felt like an impostor?

Yes, doing something I wasn’t supposed to be doing. I was floundering, so I got a job as a serigrapher.

Making serigraphs is exacting work.

It was horrible, but it taught me so much about color mixing.

How did you overcome the self doubt?

It took a long time to pound that out. The self doubt is still there, I have to work against it all the time. When I was working as a serigrapher, I got married, I was 40; we started a family right away because, you know, I’m ten years behind on this whole thing. I went to work one day at the serigraph company, and the owner said, “I won’t need you today.” I thought, “Oh, good, I’ll go down to my studio and paint.” Well, he said, “I won’t need you tomorrow either,” “I’m laying you off. I’m downsizing.”

Right after you started a family?

Susan was seven months pregnant. I went home and [told her]. She said, “Well, let’s see if we can make it as an art family.”

I was hoping you would tell this story. [Laughter]

So we did. It’s been really hard, though. She was from Boise, so we moved back and rented a little house. It was so little we could hold hands in the living room and touch either wall with our arms outstretched. We had two kids by now. We wanted to rent a larger place, but rents were so high and it’s a struggle to sell stuff through a gallery. It’s not easy.

You had established a relationship with a gallery in California, where you could sell paintings?

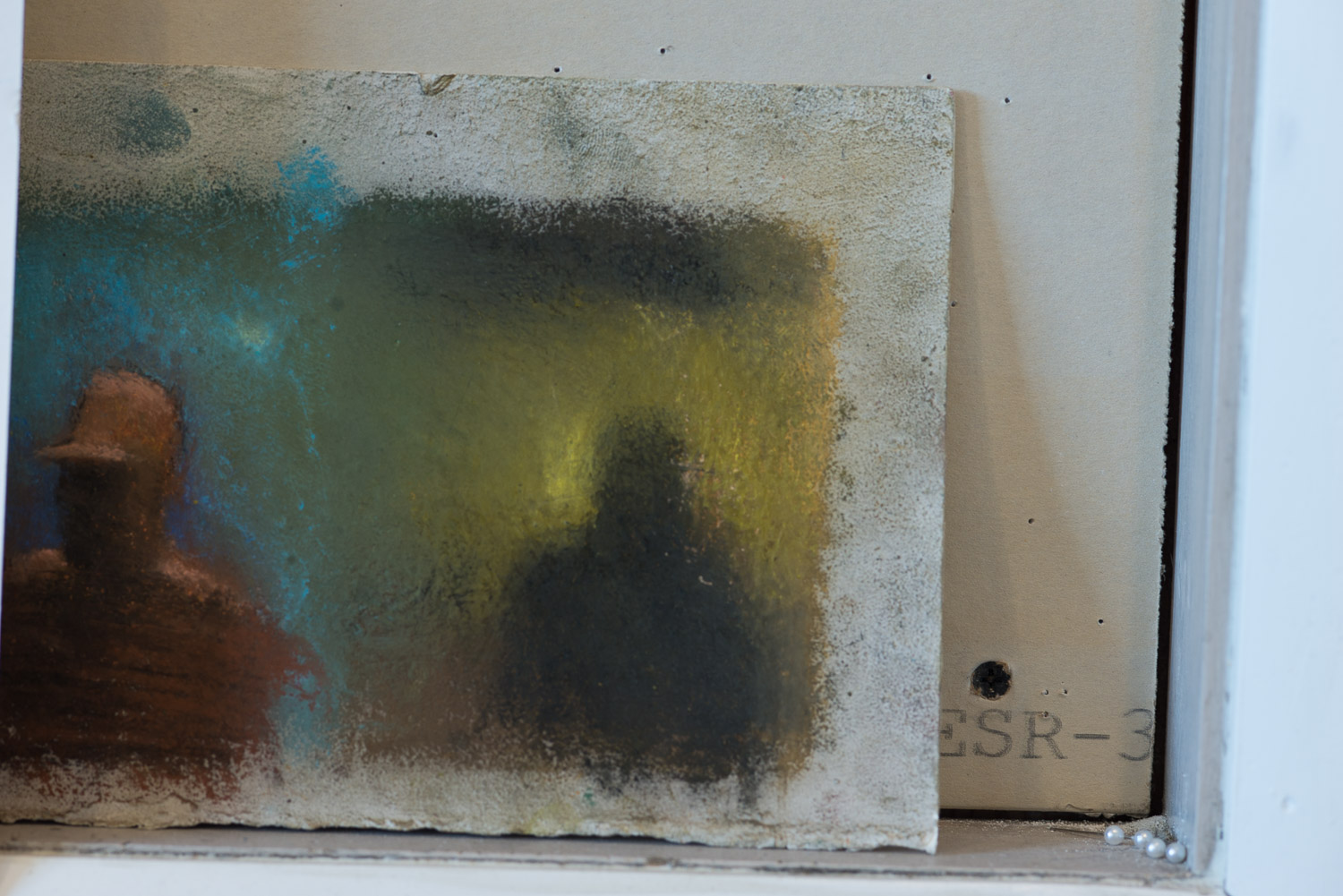

I was doing pastels, a lot of landscapes. It was selling a lot. I was concentrating on the farmland in Orange County.

I’ve never seen those images.

There’s only one here. I love those eucalyptus trees planted as windbreaks, the way they plant poplars here. There were big windbreaks and vast acreages of orange trees or strawberry fields or artichoke fields. It was so beautiful because Orange County was getting built up and out. But, suddenly, Irvine and other parts of Orange County were diametrically opposed to the suburban world.

Urban sprawl.

I painted it romantically. I dipped into the Hudson River School, dark foregrounds, light clouds, the whole schmear, to push a sense that this isn’t going to be here forever. What initially got me going was an article in The Orange County Register, “Say goodbye to your favorite bean field,” talking about development. I felt galvanized to paint. I painted it over and over and over again and found an audience with the gallery. Then I switched to a gallery in Laguna, and [they] sold, sold, sold, sold, sold, sold, and it was great. When 2008 hit, [they] shifted to not showing that kind of work anymore, showing abstract minimalist work instead. It cut me off. Now what?

The recession in 2008 comes up a lot with artists.

Everything went [sound effect]. I got in with another gallery in Laguna, but [they] didn’t want to show eucalyptus windbreaks, so I started painting ocean stuff. [There are] only a handful of those that I really love. That brings us all the way up to now. I’ve shown here with Jacque Crist, and Stewart Gallery with Stephanie [Wilde]. I’ve shown in Boston, Seattle, Park City.

You make work both designed to sell in a gallery as well as work you described earlier, following your own ideas without the constraints of a gallery or patron.

A gallery is a business. If they take you on, it’s because they’ve linked up [my work] with potential clients. If you change up what you’re doing midstream, and ship it to them, they won’t know what to do with it. Maybe they don’t have a clientele for this kind of work. You really have to think like a businessperson, not like an artist, “I’m going to paint 30, 40, or 50 of these.” I have a hard time doing that because there’s no room for playing.

It’s work.

Yeah work. That’s okay, because I’m doing what I love. When looking at other people’s work, the work I revere are paintings that seem illogical or don’t seem to have an underlying purpose; making money. Work like that hits me hard, I think, “Wow, man, that is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. It’s so completely out there. It’s not related to anything in the real world, or it is, but it’s so specific and beautifully done that it just blows you away.”

Which artists are you watching?

I started looking at photorealism by Rod Penner. Sean Scully. David Hockney. But when I painted those eucalyptus trees, it wasn’t to sell. It was because I loved being out there.

You had an emotional attachment?

It was a huge emotional attachment. And that was transmitted through the paintings, and as a result, they sold. It’s trying to find that balance, so you’re not painting in the selling way.

Because it won’t have a soul?

Yeah. So now, I’m trying to find who will take all this abstract stuff. 200 abstract pieces.

Why are you so into abstract right now?

I discovered Instagram and it changed the way I think about everything.

Really? How?

Well, because when you work in isolation, you give [the work] to a gallery, you get feedback from people at the opening, “Oh, I love your work!” But when you post on Instagram, suddenly people from all over the world have an opportunity to see it, and sometimes they respond. I look at people’s work from all over the world; it’s interesting and exciting to see how people play with forms. Instagram gave me the right and the acceptance to explore.

Maybe you feel inspired and validated by looking at work that makes an impact on you?

There’s a guy, Hernan Ardila, completely abstract. His work just sucks the air right out of me. There’s Marco Tirelli, Italian, who does big, giant shapes; I’m drawn to shapes.

I say forms. You say shapes.

I love Anish Kapoor.

His work is sculptural, that’s a form.

Yeah, it’s a shape. [Laughter] Do you know he owns the rights to use the blackest pigment on Earth?

Yes, the weird paint that’s the deepest black, I think he owns the copyright?

Yes, the weird paint that’s the deepest black, I think he owns the copyright?

So, another dude invented a paint, almost as black, and in the advertisement he said anybody can buy it, anybody can use it, except Anish Kapoor. It was tongue in cheek.

Art world drama.

It’s funny. I look [at work that inspires me] and I think, “Wow, man, I’ve got to get on it, go, go go, go, go.”

You found your people. You found the aesthetic and the concepts you are really interested in.

Yeah, and [a place to] contribute to that. Bouncing ideas around.

How do you use photography in your process?

That opened up for me with the advent of a smartphone. My first smartphone had an editing program that changed the way I think. I remember literally crying when that smartphone died.

Awe.

I got another one. Same company, but they didn’t have the same editing program, but I found Snapseed.

Having an easy way to modify a photograph is really important to you?

Yes, because [the editing I do] takes it out of the photographic realm, and more towards the idea of paint.

It’s the first level of abstraction?

I can do stuff to the photo that inspires the painting, or renders out textures.

You seem to have a lot of ideas; sometimes one grabs you, and you settle enough to flesh it out?

Settle enough is the key word. I have a really hard time pulling those ideas, isolating them, sitting with them, and finally doing them.

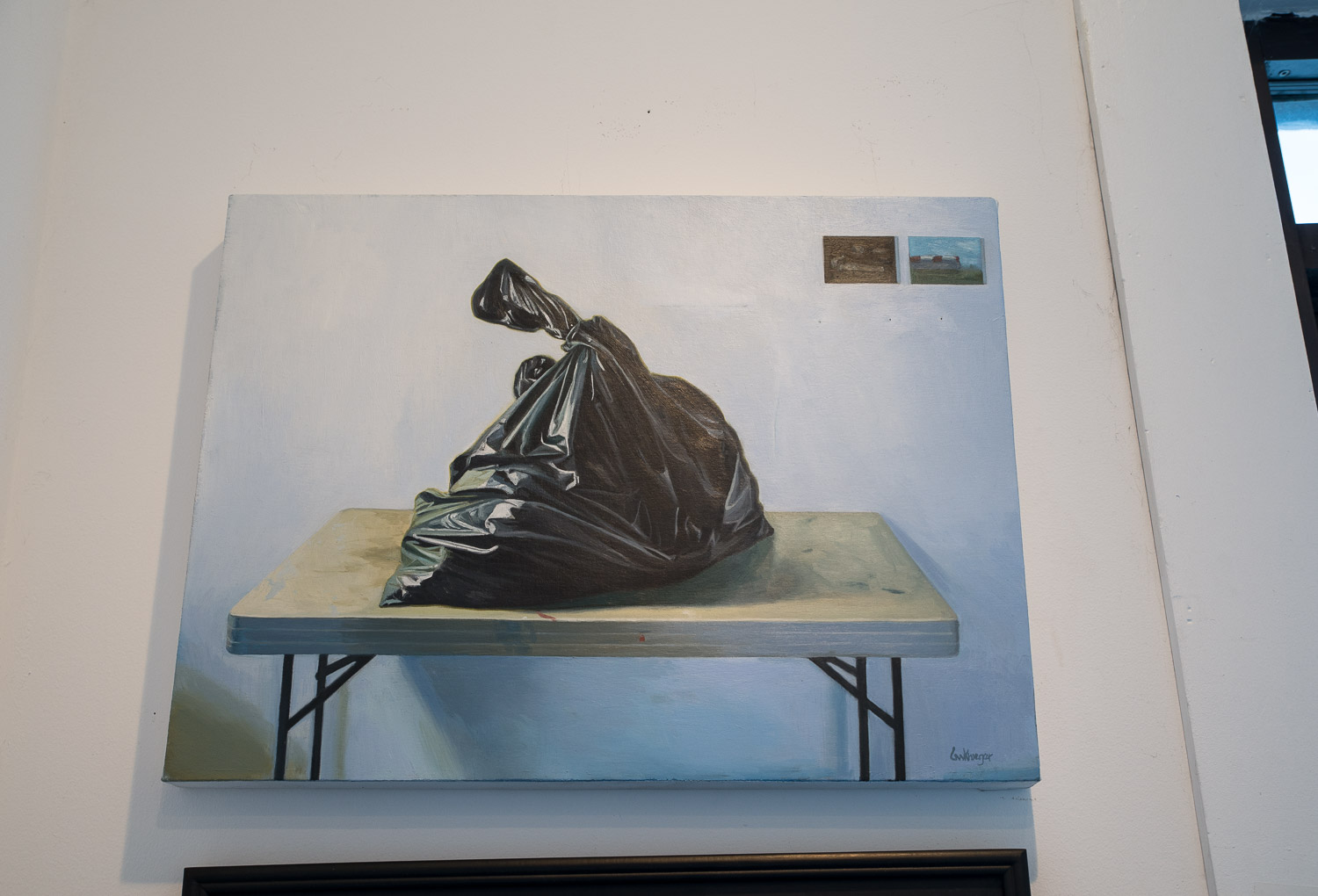

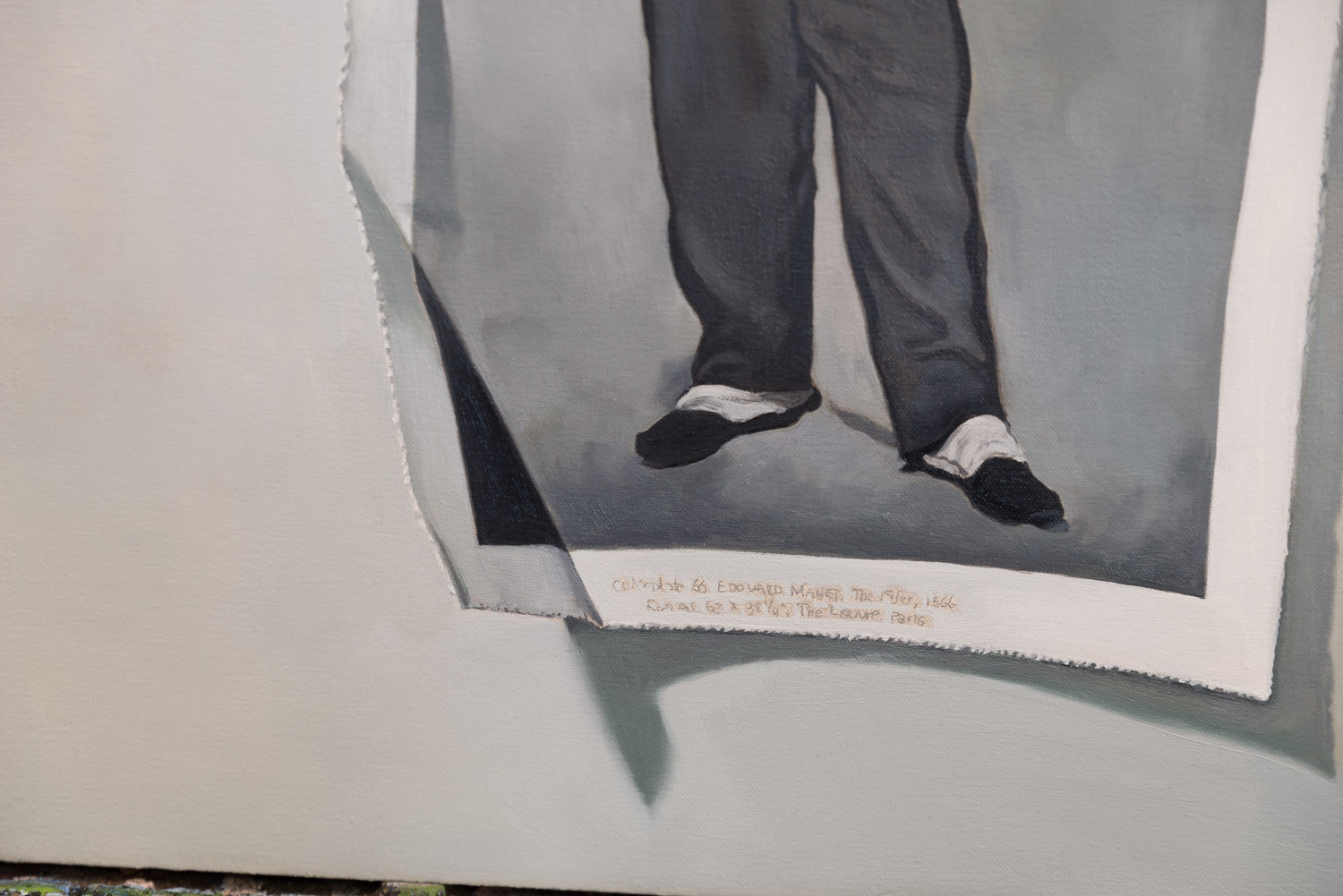

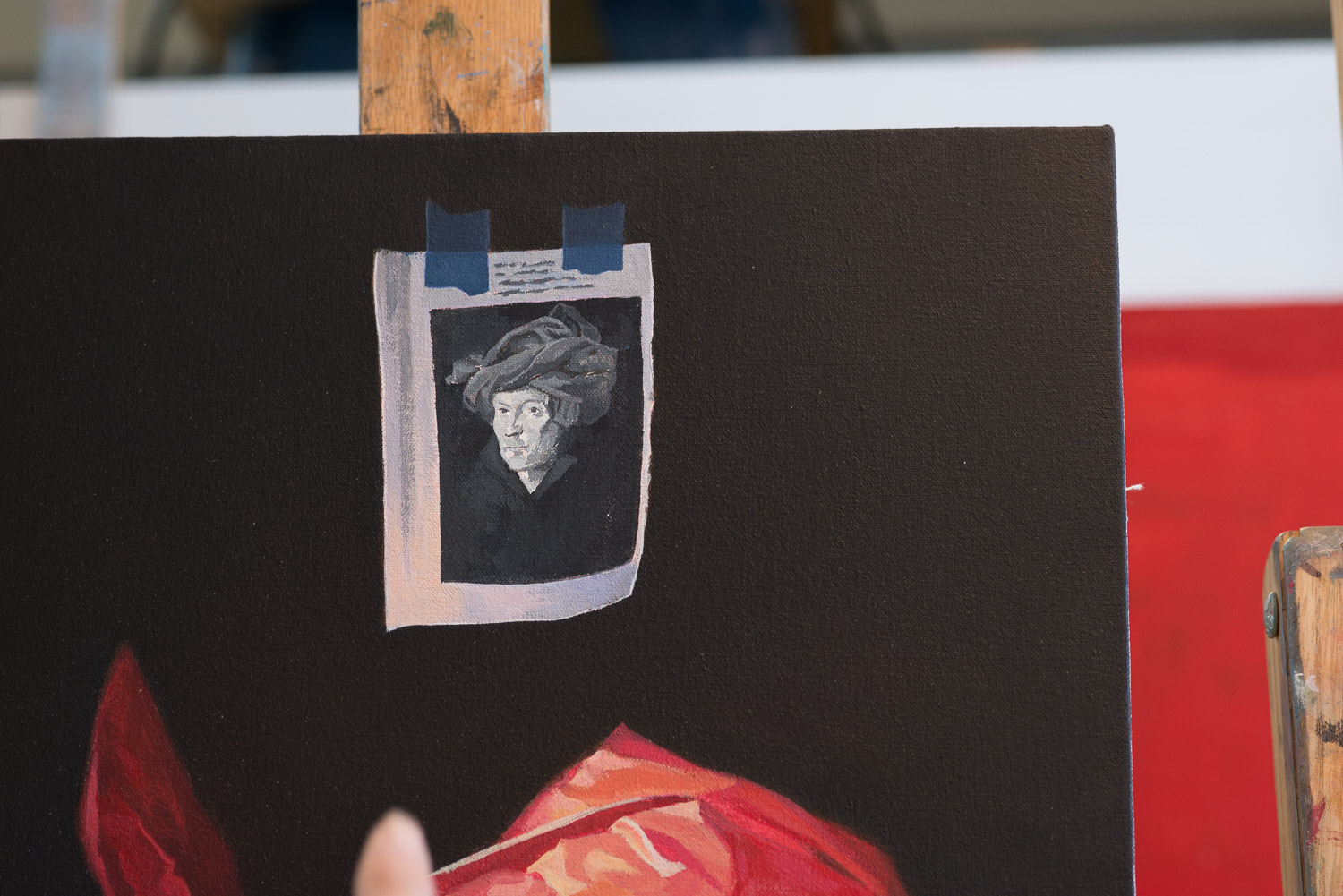

Me too. Let’s talk about this painting, it’s kind of trompe l’oeil.

Total trompe l’oeil. They’re satisfying to paint. I think they’re funky.

What is it?

Photocopies of famous paintings that I like. I’ve made it look as though they’re taped to a wall. The tape is rendered as well as the painting, and the folded paper. It’s art history, slash, trompe l’oeil, slash, still life.

It’s meta. I can collect your paintings of a collection of photocopies of a collection of famous historical artwork.

It started with Man in a Red Turban by Jan van Eyck. I haven’t carried that out yet completely. Then I’m going to paint the Annunciation, then St. Francis in Ecstasy.

We are almost out of time.

Make it a good question.

In your artist statement you talked about feeling a sense of urgency to paint. What is that?

I’m 66, and I’m thinking I’ve got quite a few more years to go, hopefully, and I want to paint some paintings that really knock my socks off. And get them into a good space with a gallery owner who [believes in them].

Some people say they make art just for themselves. I’ve never identified with that. I want to share it with someone who gets what I’m doing.

In the end, for me, [the question is:] “Does it hit me hard, here?” And if it does, I feel really good about it

If you could go back in time and give yourself advice, what would you say?

Don’t go into communications. I would have stayed in art, I would have gotten an MFA, and I probably would have taught at a university, taught studio art.

You would have been eating, sleeping, living, painting.

I’m doing that now, anyway, so. Susan says, “You do this 24 hours a day.”

You really do.

I do.

Garden City

December 4, 2019

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.