Creators, Makers, & Doers: A. H. Jerriod Avant

Posted on 3/24/21 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton ©Boise City Department of Arts & History

A. H. Jerriod Avant, poet-in-residence at the James Castle House, is a doctoral English student and instructor of record at the University of Rhode Island. Jerriod explains some of the tools of poetry and how he uses them to make meaning, and how getting a little distance from home is sometimes what’s needed to really appreciate it. Where’s home? Longtown, Mississippi, in the northwest corner of the state, rich in soil, Black culture, and a tradition of storytelling. Home is a goldmine of inspiration. Jerriod says he’s happiest when indulging his curiosity and when being stretched. What’s it mean to be stretched? It’s walking a fine line between accuracy and play, it’s sitting in an uncomfortable moment that has something to teach you, and it’s learning the rules so you can subvert them.

Have you settled in?

Have you settled in?

It’s going good. I’ve found some kind of rhythm and I feel like I have everything I need.

What do you need?

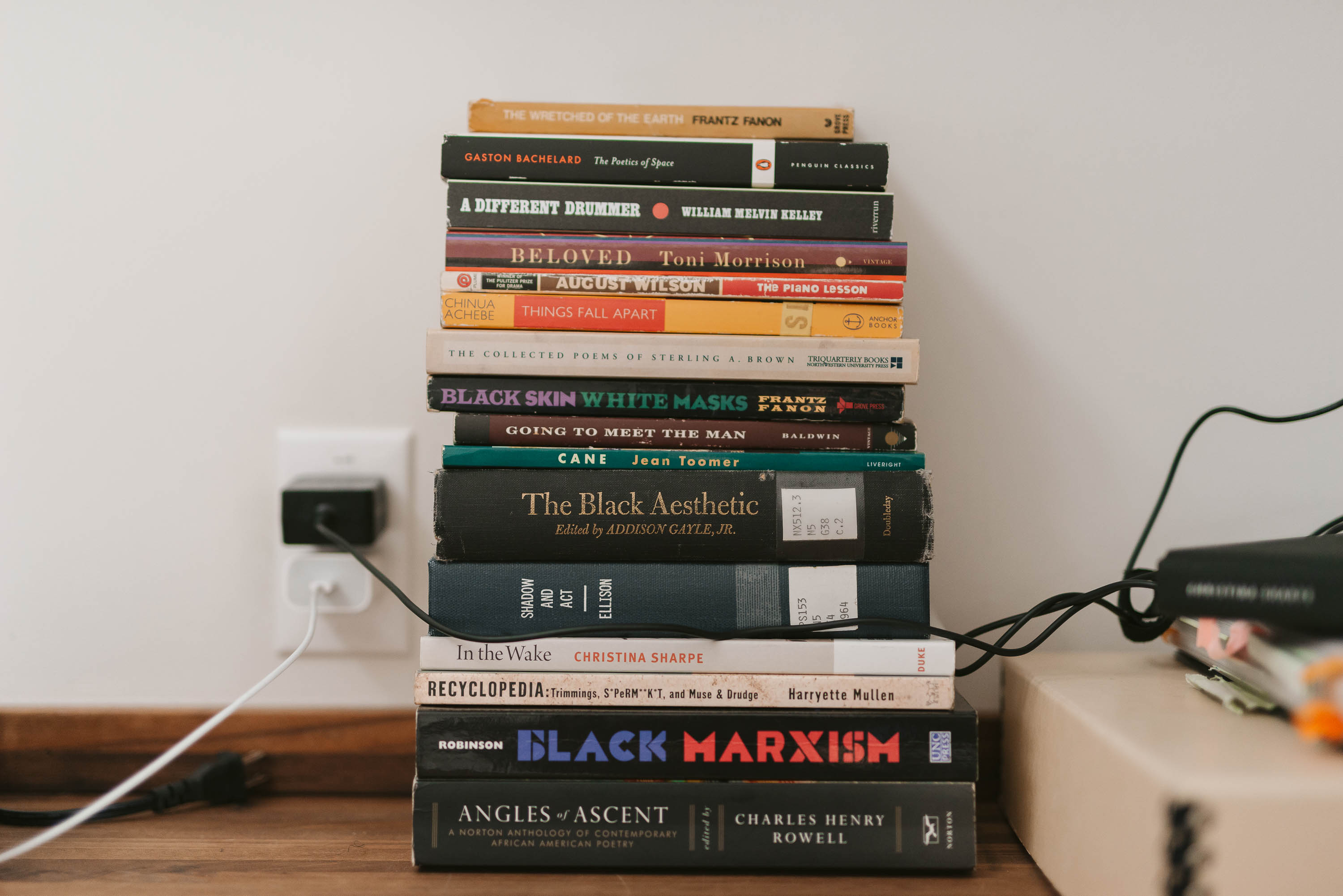

Groceries, space, pencils, books, photographs, cameras, time.

What kind of space?

What kind of space?

Space where I can hang photos and watch them accumulate, space where I can be vocal and hear the things I’m writing out in the air and make sure they sound all right.

I’m really intrigued by what happens when you put words in the air.

So many things happen, it’s always been part of my writing process—if I end up repeating a phrase or a sentence over and over, that eventually works its way into a poem. But I tend not to commit it to paper until it sounds right in my head or it sounds right out loud. Having space to do that freely without getting strange looks [chuckling].

That’s probably a good feeling when you find the right word.

Yeah. Sometimes it can feel right but it won’t sound right.

Why?

Words that I’m less familiar with might sound right but they won’t feel right because I just don’t have that much experience with it, with a certain word or a certain kind of word. [Chuckling] I don’t know. But, a word like cornbread is very familiar to me. It’s been a part of my lexicon since before I knew what a lexicon was.

What kind of phrases are you repeating right now?

Phrases that I’ve written down in conversations with my mom, back home, whatever comes up in conversation that strikes me. That’s usually part of my process, scavenging.

Are you a word scavenger?

Yeah. I did say scavenger. Collecting and picking up language from wherever and mixing it with other types of language, other dialects, other dictions, seeing how they collide and how they blend. Or don’t.

I would be interested in how they don’t blend.

When I think about blending, I’m thinking about music, I’m thinking about assonance or dissonance. Dissonance, if you’re thinking about music, is a lack of harmony within the chord structure. When I think about music and writing, I think about the way words or syllables create a certain tone, a certain feel. Assonance and dissonance suggest ideas that can help us get there and can keep us from getting there.

Can keep us from getting there.

In poetry assonance is the repetition of two or more vowel sounds in succession, and consonance is the repetition of two or more similar consonant sounds in succession. So when you get a repetition of either one of those, you get assonance and consonance. They’re just tools, you know.

Tell me more tools of poetry that you use.

I use a lot of repetition. I use some rhyme, but what I’m thinking about and writing now that I’m using so much rhyme that it ends up being sort of disguised that you don’t hear it as much as you should. It’s fun to get to experiment with it. A lot of the typical poetic tools, metaphor, parallelism, irony, chiasmus.

What’s chiasmus?

I think Terrance Hayes has a line that says, a bandana is a useful handkerchief, but a handkerchief is a useless bandana. Like if you think about bandanas in gang culture, you could use a bandana as a handkerchief, but just any old handkerchief won’t necessarily be of any use as a bandana—you hold an idea on one side of the sentence, but it’s reversed on the other side of it.

It’s kind of like a one‑way street.

Right, right. You see one thing going down the intended direction and you see another thing coming down the opposite.

What are some themes that you use in your work?

I write a lot about family, my parents, my brothers, my uncles, aunts, people I grew up with in the church. I bring all of them into my poems at some point.

Do people ever ask “Why did you write that about me?”

[Chuckling] I haven’t had it be a problem yet. A lot of times my mom will read a poem, and she’s like, “Oh, you be listening, huh?” I’m always sort of paying attention in ways that I haven’t always paid attention.

Observing?

I’m a good observer. I bring so many people from my real life into my work. Family’s there, race, animals, music. I think there’s a sense of danger in some of my work, I love that. I like being able to create a feeling, you know, with a poem, a feeling of being lost or being afraid or being in danger, danger to yourself or endangered by something or somebody else.

A threat?

Yeah.

I noticed some of your writing is very conversational. Like I can almost hear the voice of the speaker, and it’s not always you, it’s very subjective, specific. Sometimes you write in first‑person; it’s definitely not detached or using an omnipotent narrator voice.

Uh-uh. No, I can’t [chuckling] I can’t afford to do that.

Thank you. Why?

I don’t know. Like, there’s so much else before, you reach for that voice.

What’s before that voice?

Everything that’s tangible and breathing. I have questions about so many other things that I haven’t asked before.

Questions make for powerful inspiration.

Right, right, right. I’m happiest when I’m curious or when I’m discovering or when I’m being stretched in some way.

Becoming. Some people call that becoming. You’re in the middle of a doctorate program at the University of Rhode Island, do you struggle for space there?

I had a roommate and I couldn’t just mouth things out loud when I wanted, in the apartment. But even now, I live alone, I go to the woods a lot, and I’m outdoors. A lot of times I use that space and time and air for that purpose. I love being out in the woods, I write so much in the woods—

That’s your place?

That’s a really good place for me.

How do you feel about the big open air here? It’s all air, right?

[Chuckling] Yeah, it’s all air. It’s good. In in a strange way it feels a lot safer than the woods that I’m used to because I can always see my feet when I’m walking. And in the woods back home, unless you’ve got a machete or unless the path has been cleared previously you can’t see your feet. I feel at ease out in the woods here, because of that. The air is nice.

What’s so bad about not being able to see your feet?

You never walked up on a snake.

No.

That’s what bad about not being able to see your feet, rattlesnakes, water moccasins, and venomous snakes [laughter].

Where is home?

Home is Longtown, Mississippi, about 45 minutes south of Memphis, Tennessee, so, way northwest Mississippi, right on the edge of the Delta and the Red Clay Hills.

What’s the Delta?

The Delta is the Alluvial Plain, this area of flatland that is next to the river in the northern half of the state. But culturally it’s the most densely populated area for African Americans in the state. The soil is rich. It’s rich in people. It’s rich in culture. It’s rich in all of those ways. It’s flat, hot, and humid in the summer. It’s gorgeous. I hate the humidity. I never get used to it. It’s probably one of the things that I hate most about the summer. But everything is so green and lush and so beautiful you could almost forget about the humidity.

Yeah?

Almost [chuckling]. From the river you get to the Delta, and then from the Delta you get to the Red Clay Hills. You can see for miles ahead of you, in some parts of the Delta because it’s so flat. There’s a lot of kudzu, a lot of uninhabited forest, a lot of pine forests being harvested for timber.

Some of what you were writing about was deer season.

Lots of deer. My folks rent the land out and hunters come in and hunt on our land, it’s a big deal. They’re everywhere, running for their lives. Which is very different from some other places where I’ve been around deer; it’s a lot different.

In what way?

Well I’ve been near deer in Rhode Island and in Colorado, and I could just walk up and touch them.

Urban deer?

Yeah. In the cul‑de‑sac or asleep in somebody’s backyard. They’re a lot more relaxed in some of those places. Whenever I see them at home I have either hit a deer, driving, or dodged a deer, driving. Or, if I see a deer out in the yard, it sees me before I can really set eyes on it, and then it’s running because it’s used to running for its life in those parts. Yeah, it’s a different place.

It’s a place of danger.

People hunt deer all over, but I remember growing up, my father drove a school bus, and I remember being on the bus seeing deer outside of deer season, and some kids would make the formation of a gun and point it, as if they were shooting, you know.

Do you use deer as a metaphor in your work?

Absolutely.

Yeah.

I mean, yes and no.

I feel like the conversation we just had was metaphor.

Yeah, kind of [chuckling].

[Long silence]

I don’t know which question to ask now.

[Chuckling]

None of these flow from there.

Just throw one.

Well, I guess, what part does honesty play in your work?

Things I’m curious about—in order to really, you know, satisfy the curiosity, I have to be honest about what it is I’m curious about. When I’m telling stories, honesty and accuracy go hand in hand. Whenever I include somebody else’s role in the story, honesty can allow or permit a level of vulnerability but also respect. It’s tricky, I always want to be honest to the story, as much as everybody involved is okay with it. So if I achieve that, those are the ways I engage honesty. I don’t— it’s hard for me to make stuff up. But I think there is something to be said about play and making stuff up. You’re not necessarily being dishonest, you’re playing.

Play, that’s a great theme. Play is a special place where I have permission to be dishonest. Is that one way to put it?

I think you can put it that way. I play around a lot with language and intentionally break the rules of what folks would call standard American diction. And rules of the language itself, like grammar rules. And so in the way that that is dishonest or breaking the rules, of course I take permission to be dishonest.

Honesty or accuracy to the story. There is an element of compassion for the people, to honor their truth to the story and not simply one perspective?

Right.

Is that difficult?

It can be because it could be the same story with three people involved, and everybody has a different take on it. So how do you blend all of those perspectives inside a single poem; or do you spread it across three different poems; or, you know, how do you deal with it? I think sometimes I give myself space in the poem to roam and figure out how we’re all connected in the story, or how we’re all affected by it. A shared experience could be just the story having an effect on us, and that could be the common theme, as opposed to everybody feeling the same way.

How we interpret the tangible, like you were saying, is going to vary from person to person. Are you a storyteller?

I tell stories sometimes. In my most recent work I’m giving myself the freedom not to. And to not feel like I have to tell a story.

Not be dependent on story?

Yeah. But, I don’t think it’s a thing I won’t come back to, because my upbringing—my whole life is from a storytelling tradition, so . . .

Tell me about that.

Well, you know—

No, I don’t know, that’s why I’m asking.

[Laughing] Well, I’m talking about being Black and working out of a Blues tradition, out of a Southern tradition, where storytelling is like the benchmark for somebody from a place like where I’m from. Storytelling is in all the institutions, it’s in the church, it’s in the school, it’s in the music, it’s in singing, it’s in marching bands.

I grew up going to a Baptist Church too, but I bet we had two very different experiences.

When I’m back home, in my mom’s house, if you sleep in the house on Saturday night, you’re going to church on Sunday morning.

Yep, same.

In her house [chuckling]. So when I go back I’ll see people who were adults when I was a little boy, who now have these ways of reminding you they’re still your elders even though you’ve grown.

So now they’re—

Now they’re elder‑elders. I don’t know, the church was a place where we were made to get up in front and speak in certain ways, holding office, like being an assistant superintendent of the Sunday school, and we did plays for Christmas and Easter. So being comfortable speaking in front of people has helped me in a lot of ways to feel comfortable telling a story.

What kinds of stories?

Most of the stories I’ve written or told in my poems dealt with grief, loss, and how that affects different members of the family; how we sometimes get in the way of each others’ grieving processes. I’ve been curious about—how do we allow for another person’s full manifestation of grief to occur in a way that doesn’t interrupt it? That doesn’t make people feel ashamed for choosing to grieve the way they do, or for subconsciously grieving the way that they do. Because I don’t think we always get to choose how we grieve.

If we did, we wouldn’t be human.

Right. Sometimes it’s habits that we use to grieve. Sometimes it’s new things, sometimes it’s whatever’s closest. Most stories that show up in my work deal with familial grief and those kind of losses.

Your father passed away; that’s the lens I’m looking through when you talk about grief.

Those are my longest or more sprawling poems, in an attempt to give myself time and space to think through a beast like grief [chuckling]. I took liberties to not package it tidy and neat, but to let it sprawl, let it linger and see where it goes. We have such a huge family, especially on my mom’s side. Whenever I’m writing about family I like to give it room, give it the space it deserves. I don’t think I’d be able to do any of the things I’m doing without these people.

Beautiful. You were talking about honoring all the people in your stories and not discounting them. I feel like going to a liberal arts school taught me to be a critical thinker, to look closely at how I was formally and informally educated about gender, class, race, and identity. I see a lot of artists come out of the liberal arts with a new perspective on where they came from.

I think you’re spot on. I think for me one of the reasons I did a second MFA was because I had never lived anywhere other than the South or the Midwest before my second MFA, and so I sort of needed all of my notions on race and gender and sexuality and nation and all that kind of stuff to be challenged in real time. The time I spent in New York helped do that for me. In ways it helped me see home in a different light, with a distance. A lot of times you’re just too close to a thing to really see it, and that distance can help. It wasn’t until I left and came back that I started to appreciate things that I probably took for granted while I was there.

Isn’t that beautiful, though?

Things that are vital to what I do. Like the language, the landscape. These are goldmines for me now [chuckling].

Yeah they are.

Having that distance has been really important.

What I’ve seen sometimes is that people, artists, get that distance and then use it to further distance themselves from their past. You’ve done the opposite. You’ve turned around and dug in.

Oh, yeah.

To tell the truth.

Oh, yeah, yeah.

That gets me very excited—

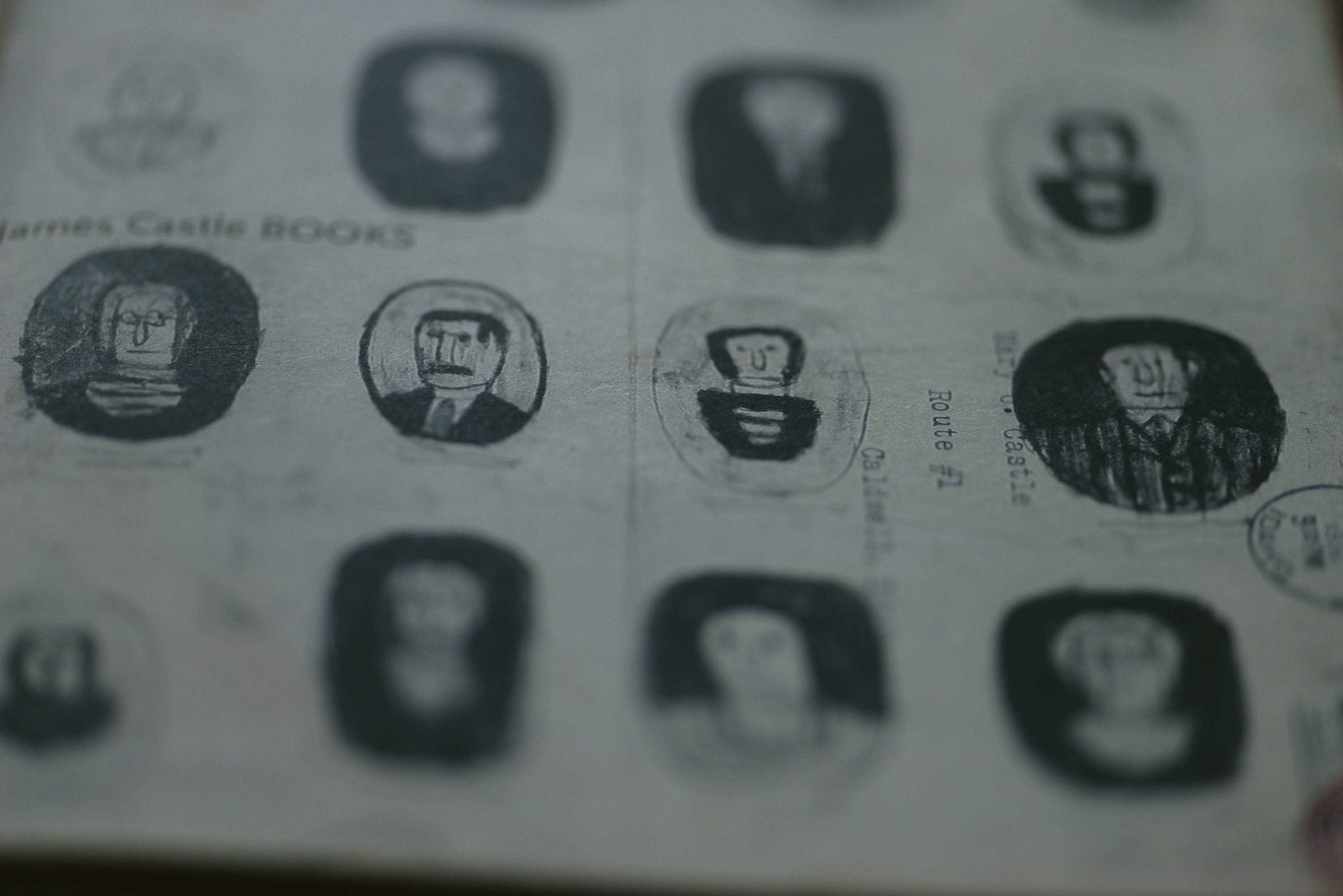

I can’t afford to let myself distance myself from … I feel like home deserves … I feel like I should give back everything that it has given me, you know? I don’t feel like there’s a better use of my time. Getting to spend time here and think about the way James Castle appreciated his home and thought about place. I think it’s a privilege to get to sit with his work and think about the ways our work is related.

You talked about being challenged in real time?

When I say real time, I’m thinking about hearing it from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. Being uncomfortable in a moment that may have something to teach me, or to stretch me in some way, as opposed to reading about it, or watching it on TV, or seeing it in a museum; in these preserved or packaged ways.

Do you have ideas for your dissertation?

I think it’s probably going to be interdisciplinary. Maybe a couple of photographic essays and a collection of poems. I think they’re both going to do similar work and hopefully create a world where, you know, just for now, these are the rules.

What kind of rules?

The rule is to break the rule. Really targeting certain rules of grammar and exploit them. Privileging misspeak, and error. Even small things, like when you’re on the phone with somebody and you say one thing but they think you said something else, [because] it rhymes, but it’s not the thing you said. I’ve been working on poems where I have a sentence, and I’ll take the vowels and replicate the vowel structure in other sentences. I’ve been calling them sound tunnels. It’s been fun to see how much meaning can be found within the same vowel structures of a sentence. Inside such strict parameters. So in breaking the rules, I’ve set up a structure where even the broken rules, follow a rule. Even inside the rules that are being broken, there are still rules being followed.

What about rules versus chaos?

I don’t feel that if there is no structure there aren’t rules. If you think of structure in terms of trusses and 2x4s and bricks and planks, sure, without structure there’s probably going to be chaos. But I believe structure can be found outside of line breaks and syllable counts and rhyming patterns. There’s structures of logic, there’s structures of sound, emotion, you know.

James Castle created his own structure, a very singular structure, of his own invention.

He created an entire world.

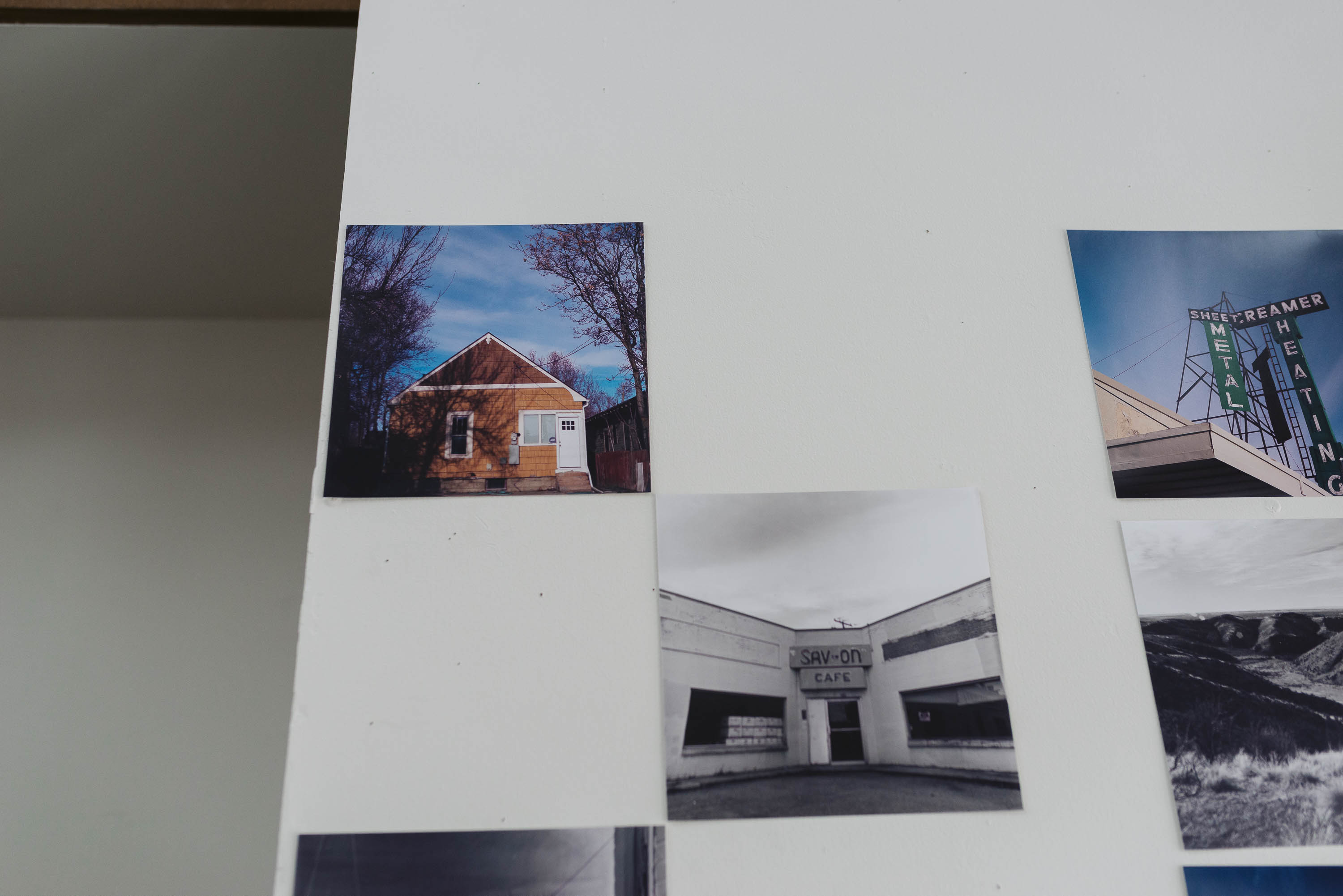

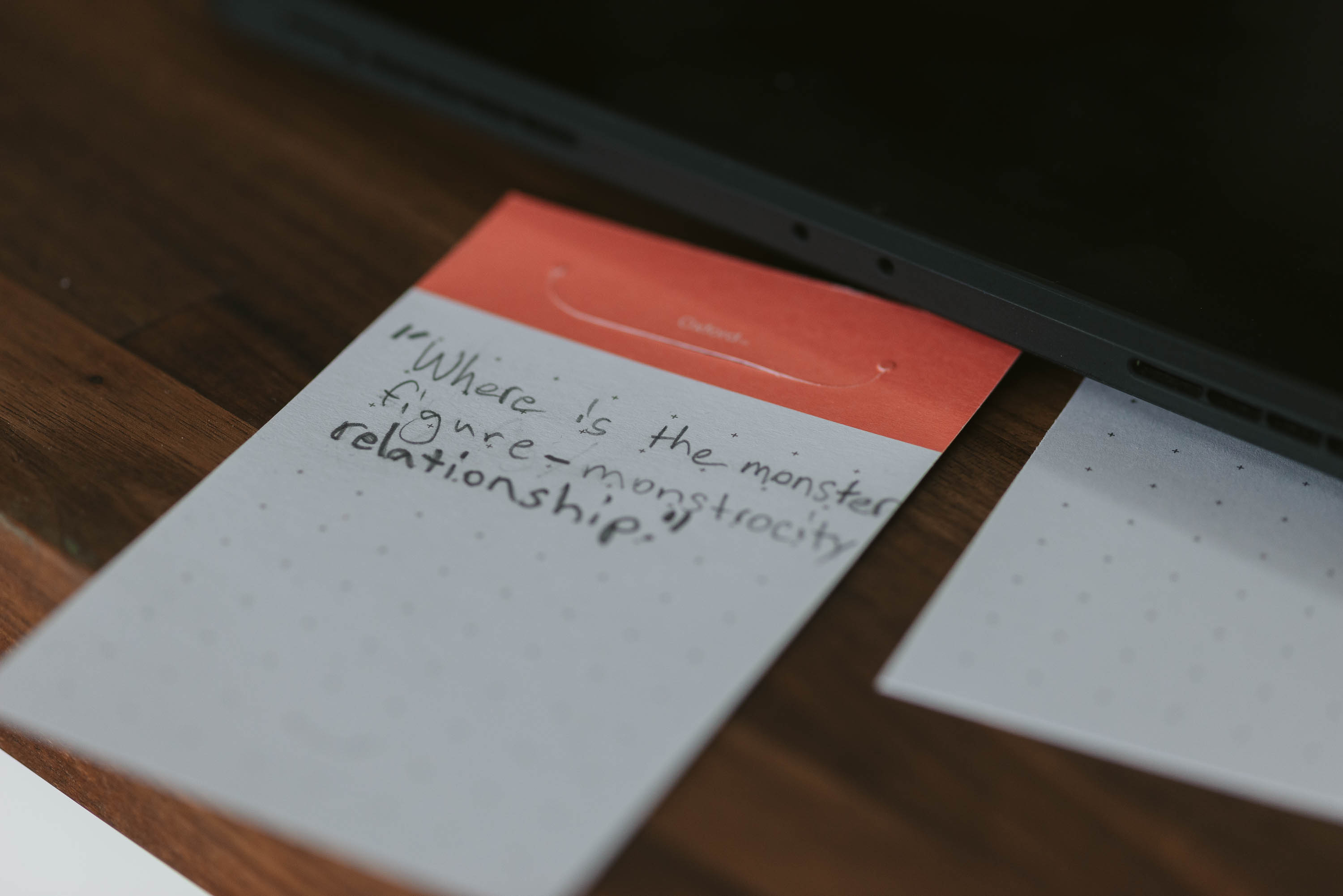

We should probably talk about the photos you have up here.

It’s a start. I’ve been sort of picking and choosing what to print. I’ll sit and look at the negatives or the scans and see what I want to spend money on. I’m sure there are going to be more foothills, more signage. Because I’m thinking a lot about the way James Castle uses language and text in his work.

Right, signs.

Signs, symbols, letters, alphabets, even those that he made up his own, altered. Hopefully, a lot more, you know, abandoned and black‑and‑whites, like the Sav‑On Cafe, and old schools. I haven’t seen a lot of Boise, but I know there must be some abandoned buildings and things around here; I’ve just got to find them.

Are you going to pair these with any writing?

I don’t know, maybe. I don’t think I would pair them with poems, but maybe in a photo essay I might write about, you know, my experience with this place would be fun to think about.

I also want to talk about your poem “Judith and Holofernes,” after Kehinde Wiley’s painting of the same name. It’s a biblical subject that’s a big deal in art history. Particularly in how different painters portray women in a place of power. The biblical reference, if I remember correctly, is that there are two warring tribes. Judith and her servant infiltrate the enemy and seduce their leader in order to save their people. While he is intoxicated, they cut off his head.

Right. Have you seen Kehinde’s painting?

Not in person, there’s two of them. It’s controversial because Wiley replaced Judith with a Black woman and Holofernes with a white woman.

Yeah. Yeah.

You’re smiling.

[Chuckling] I like all of the Judith and Holofernes paintings. I like Caravaggio’s. Gentileschi’s. I think there were a couple more.

The painting is about danger and subverting power.

Right, it’s about danger. It’s about people being abused, misused, erased, misrepresented. It’s about tyranny.

Yeah. All important things to talk about.

[Chuckling] All too relative things. I think I can find joy in this idea of punching up or subverting, some kind of structure, whether it’s with language, government, race, or wherever the oppression is coming from. A theme I want to turn inside out or turn over or flip over or damage somehow.

North End

March 24, 2021

James Castle House Artist-in-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History.