Creators, Makers, & Doers: Malia Collins

Posted on 12/15/21 by Brooke Burton

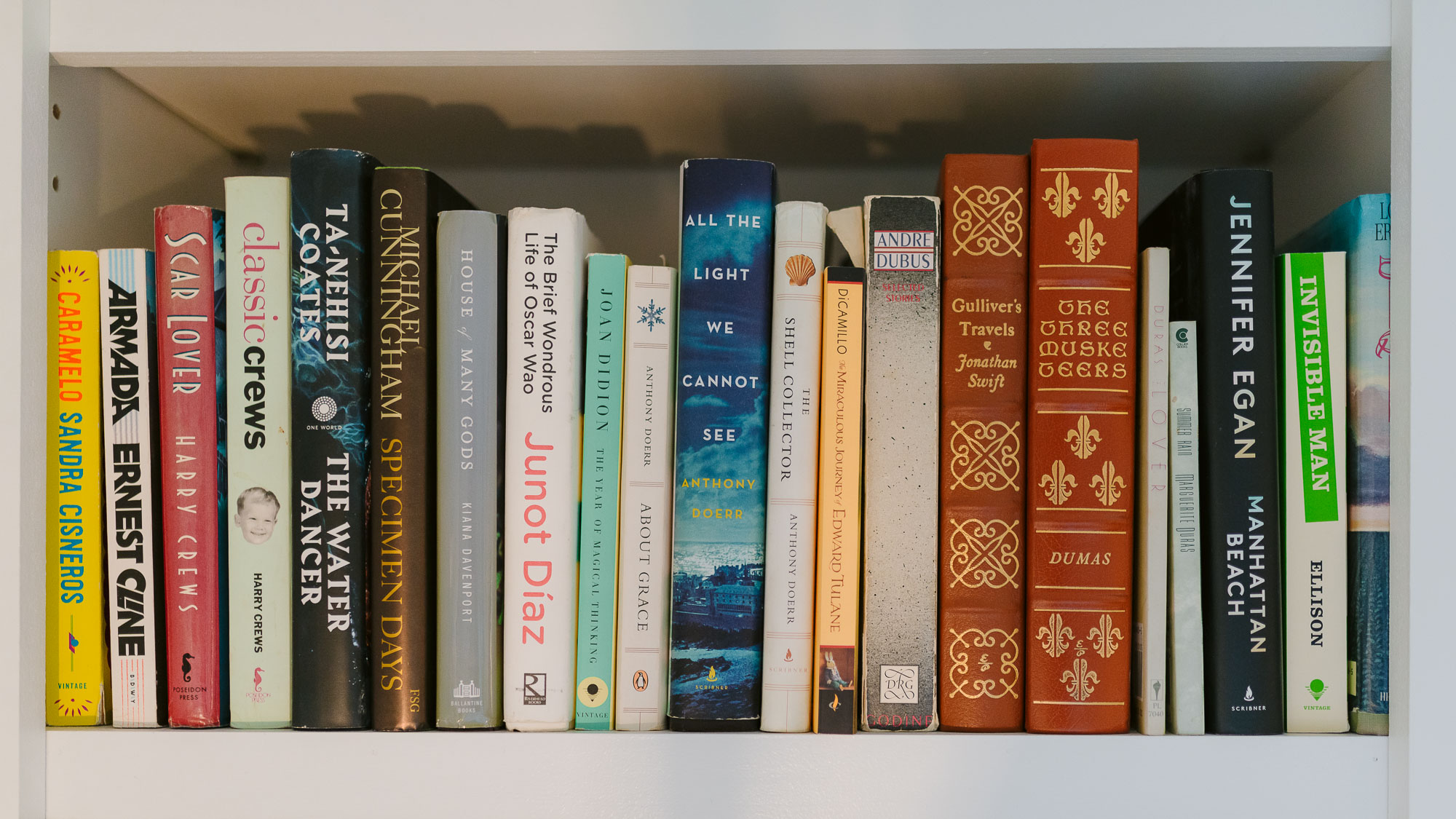

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Malia Collins, writer and educator, is wrapping up two years as Writer in Residence with Arts Idaho and is currently developing a collaborative children’s book with the Boise City Department of Arts & History, highlighting our public artworks. She explains the process of developing non-linear narrative nonfiction, using themes as strands in a narrative braid. What are the strands that come together to weave our conversation? There’s discovery in life and writing, the myth of Hawaii (Malia is Native Hawaiian), the act of being present in a moment or a memory, and, Honi, seriously the sweetest golden retriever ever. Beneath these is the undertone of a global shift and living through a pandemic. Most importantly, Malia describes the connection forged in knowing each other’s stories as a way to recognize our full humanity, such as in her work with refugees living in Idaho. Where does bliss come in? It’s complicated, but it’s in the footsteps, the smell of her daughter’s shampoo, or hearing a voice over the phone. And revisions. Always remember revisions.

What are you working on for the Boise City Department of Arts & History?

It’s an ABC book of Boise public art. There are 26 works. I’m the writer, Stephanie Inman is the graphic designer, and Arlie Sommer is the photographer.

What’s your approach?

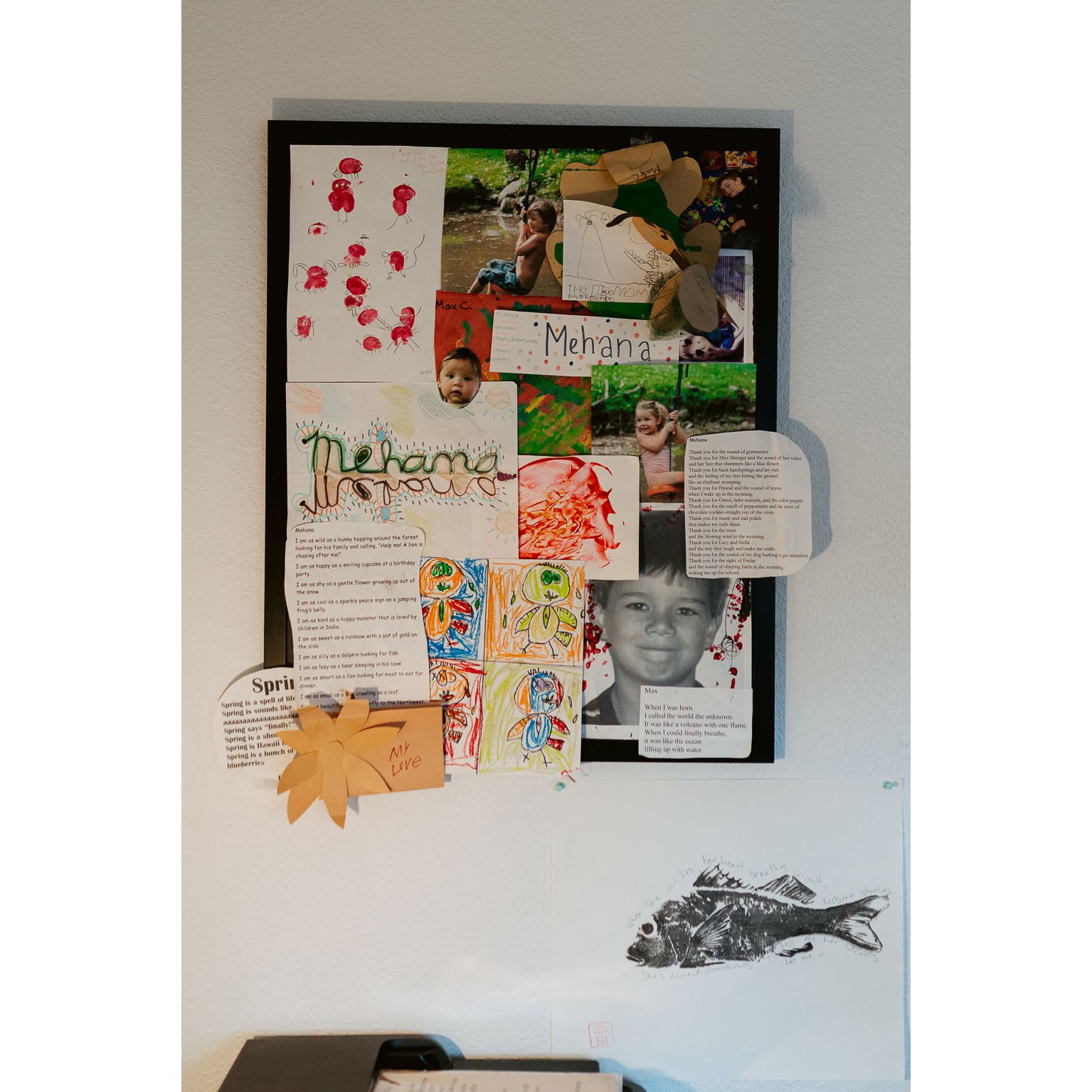

I started thinking about when my kids were little, how we spent a lot of time walking around Boise always trying to find things to do. I really wanted my kids to be curious about where they live. I’ve written a couple Hawaii children’s books. Now, when they asked me to do this one, I’m at a completely different stage in life. Max has gone off to college, my daughter, Mehana, is in high school. I started thinking, how can I imbue this book with the kind of curiosity I wanted my kids to feel when they were introduced to the city they live in?

What’s the process like?

I’ve walked or driven around to the different public works and I try to see them as if for the first time, the way a child might, and thinking about the stories they inspire in me. What’s cool about the book is that it’s using art as a jumping‑off point for kids to start thinking about stories and about themselves as creative people. I’m imagining the conversations and questions it might lead to.

How does it compare to the children’s books you wrote in Hawaii?

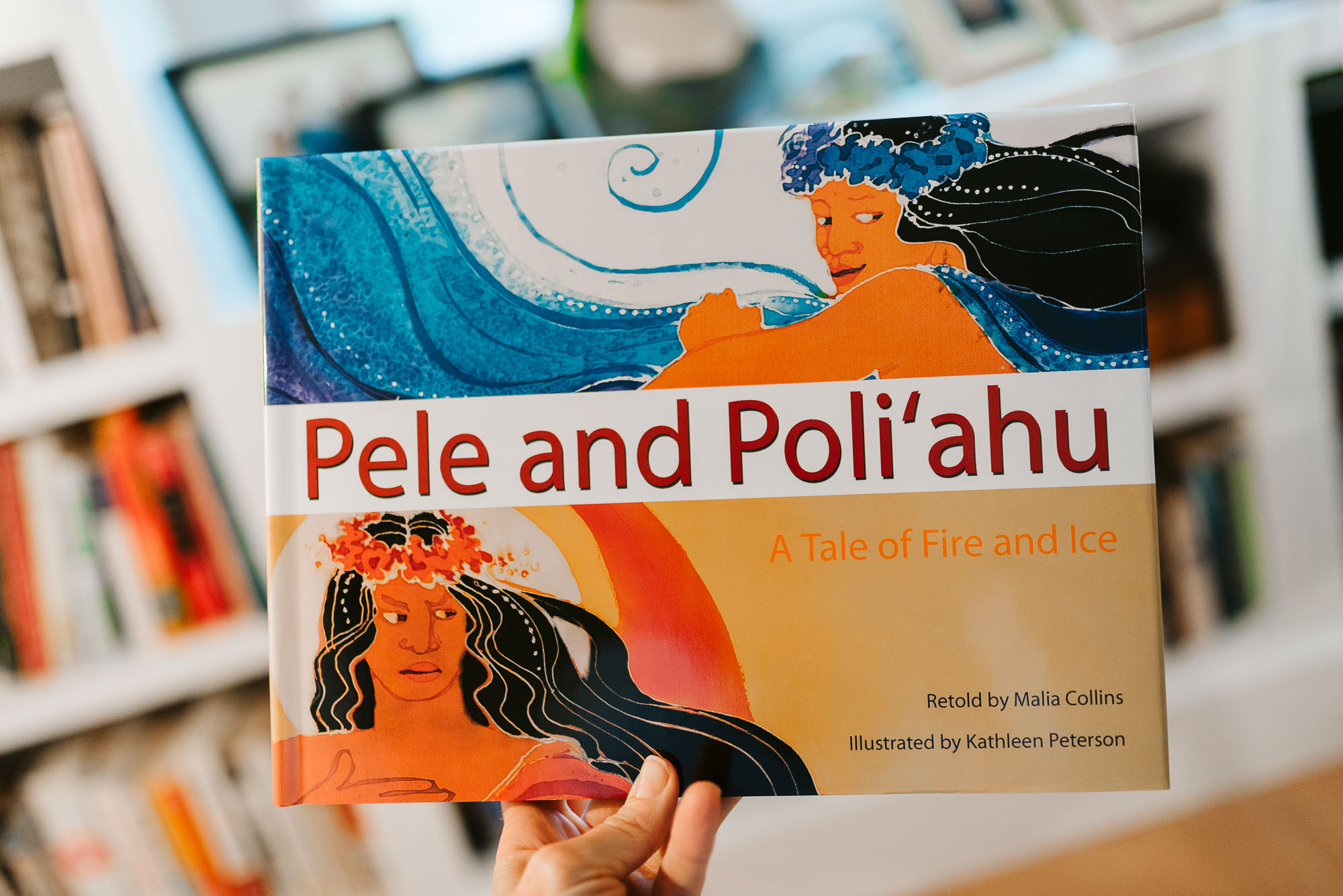

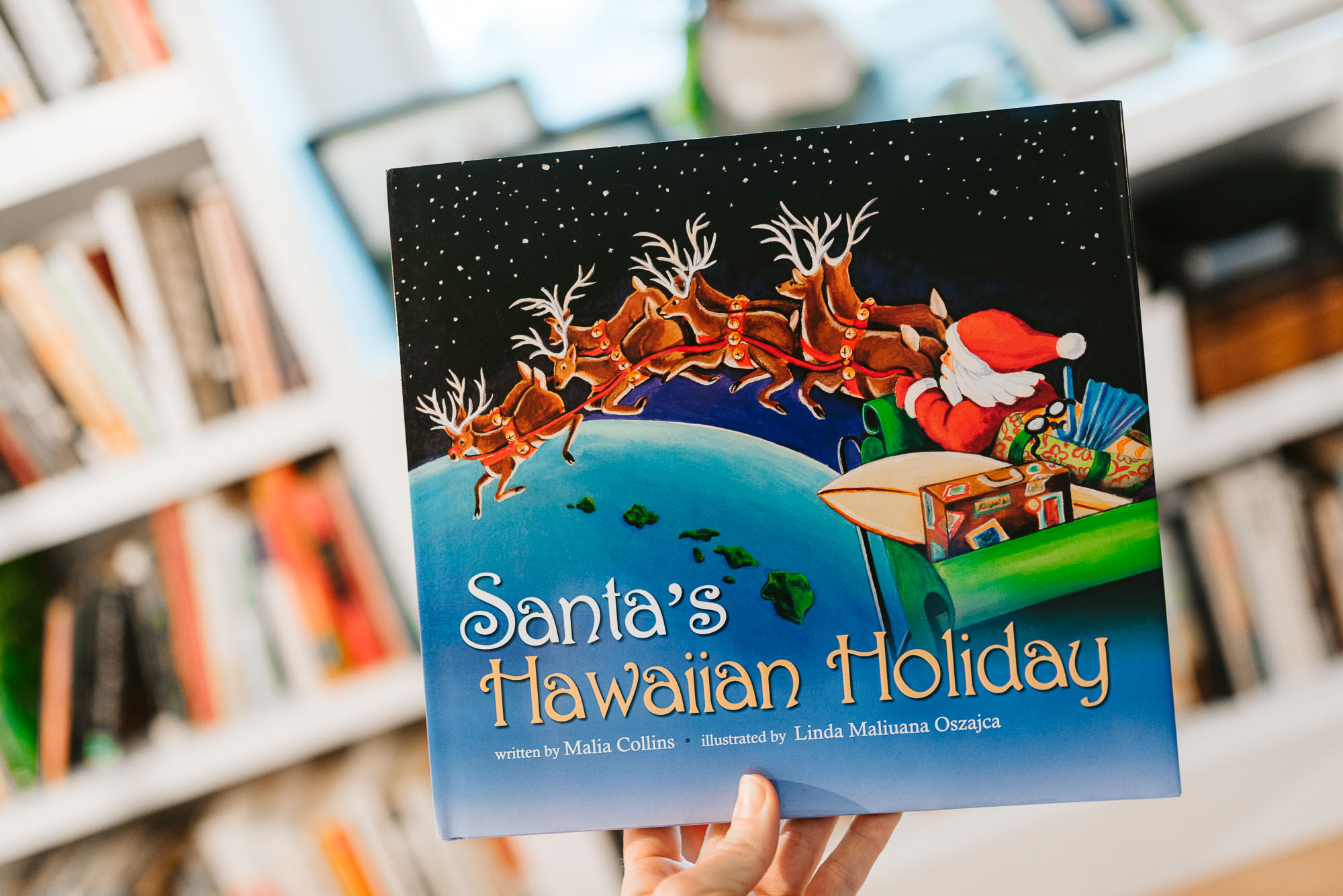

The first one is the retelling of an old Hawaiian myth about Pele, the goddess of the volcano on Hawaii Island, and Poli`ahu, the goddess of ice and snow. A batik artist did the illustrations, it’s beautiful. It’s a retelling of an old Hawaiian myth that I know because my mom’s from Hawaii Island. My other Hawaiian kids’ book is basically that Santa has a midlife crisis. [laughter] At the time, I had little kids, and I just wanted to lay down and drink something. [more laughter]

Santa’s Hawaiian Holiday is coming from the perspective of motherhood. And now the ABC public art book is from a child’s perspective.

What’s joyful about the ABC book is I started after taking Max to college, so it was a little bittersweet, going to all these places, thinking, “Oh, I remember when my kids were little, looking, you know, at the River Sculpture” or the great blue heron sculpture [Great Blues by David A. Berry] down on The Grove where the kids used to run around. I was also kind of re‑entering the world after COVID; we had kind of hunkered down. Then we were in Hawaii all summer, so when we came back, it was like Boise reminding me about what I love about Boise.

You’ve been going on field trips in your city?

Yes, and I love being surprised by things. One of the camps I taught at The Cabin was called Urban Ink; we would walk around downtown and stop at particular spots to write.

Part of wandering is discovery, that you take time to observe. To not move. Whereas, daily, I’m continually moving from one to‑do item to the next.

There’s a stillness. The first piece I went to see was the streetcar at Ivywild Park [Historic South Boise Street Car Station Plaza].

It’s in metal, by Byron Folwell?

Yes, me and Honi-

Honi?

Now I drive around with the dog. Honi means kisses and breath in Hawaiian. I used to drive around with the kids, and now I drive around with the dog. It was a super clear morning, the smoke had cleared and I was imagining how cool this would have been to get from one place to another. The streetcar ran from Boise all the way to Caldwell. Standing there, in the moment and the place–[commonly referred to as] “Ghost Streetcar”, I felt, I could imagine the sounds.

Like going back in time?

I felt transported. And that was the first entry I wrote for the book. Every day I do my morning pages, three notebook pages. I can get into a groove. When the writing’s really cooking, and it’s easy to write, you know, 800 words. But these [book] entries are short, 40 to 59 words, and I’m trying to distill the essence of what the [artwork] feels like.

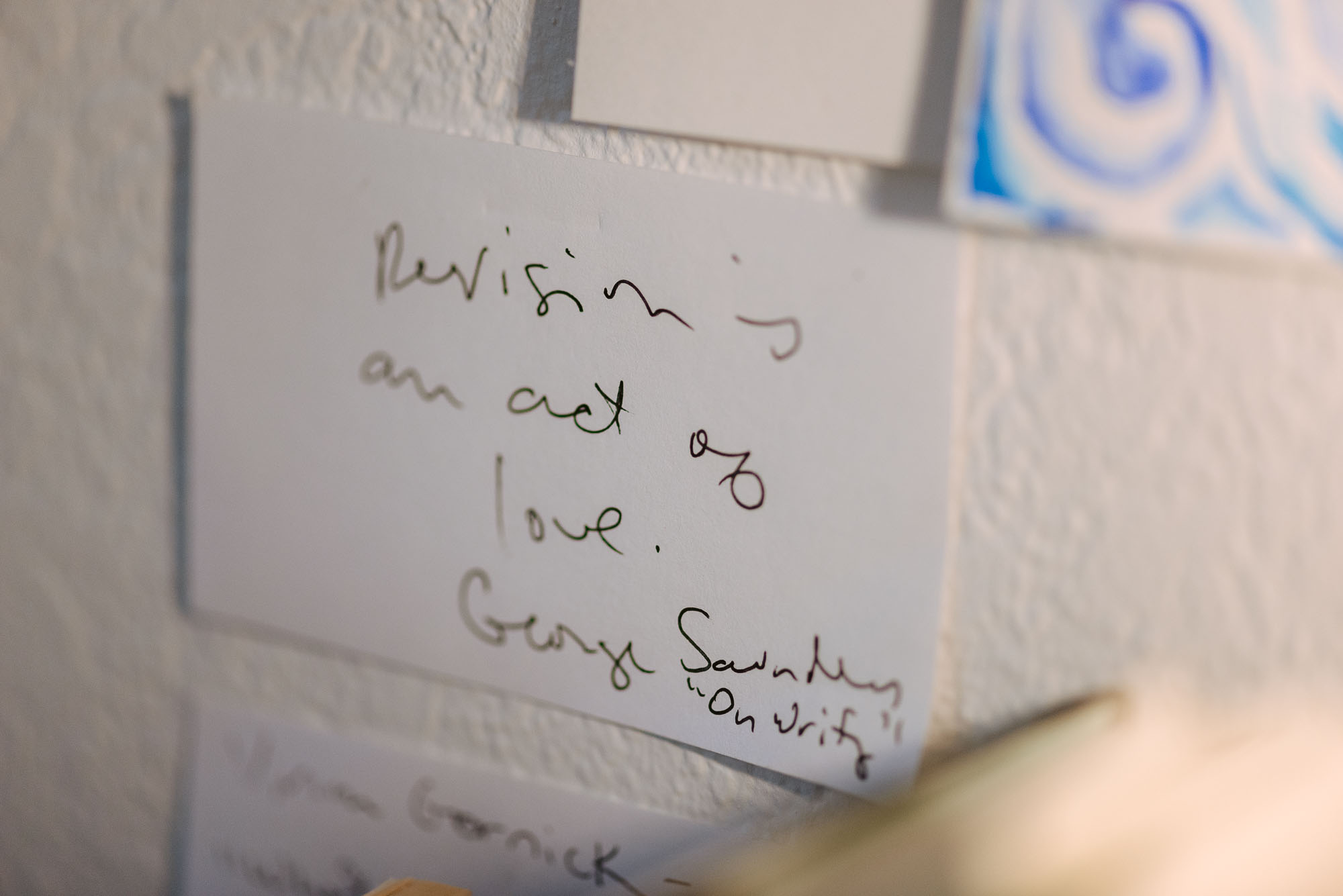

About distilling, tell me about this quote on your wall.

Oh, “Revision is an Act of Love.” George Saunders.

Why does revision need special attention?

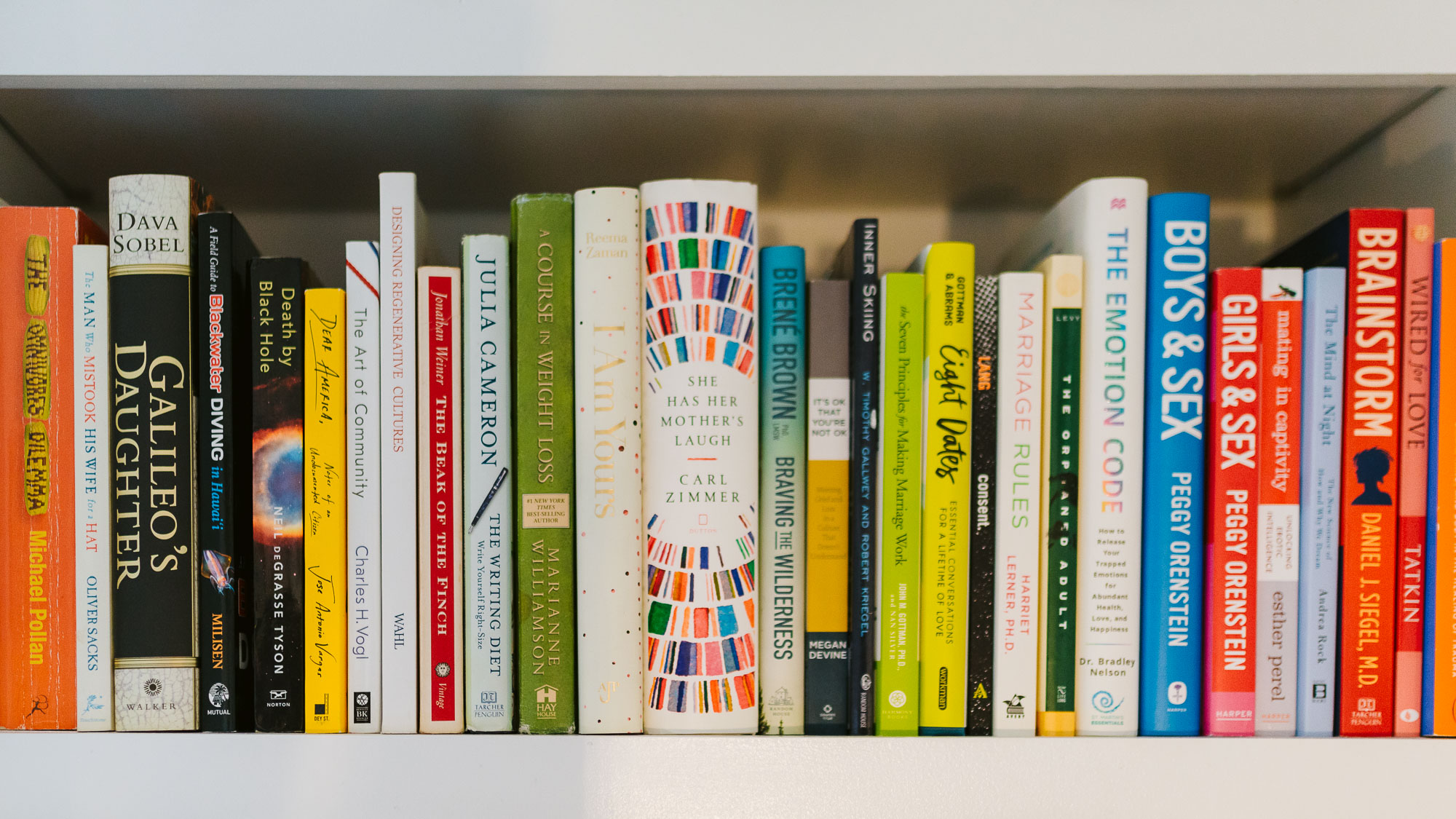

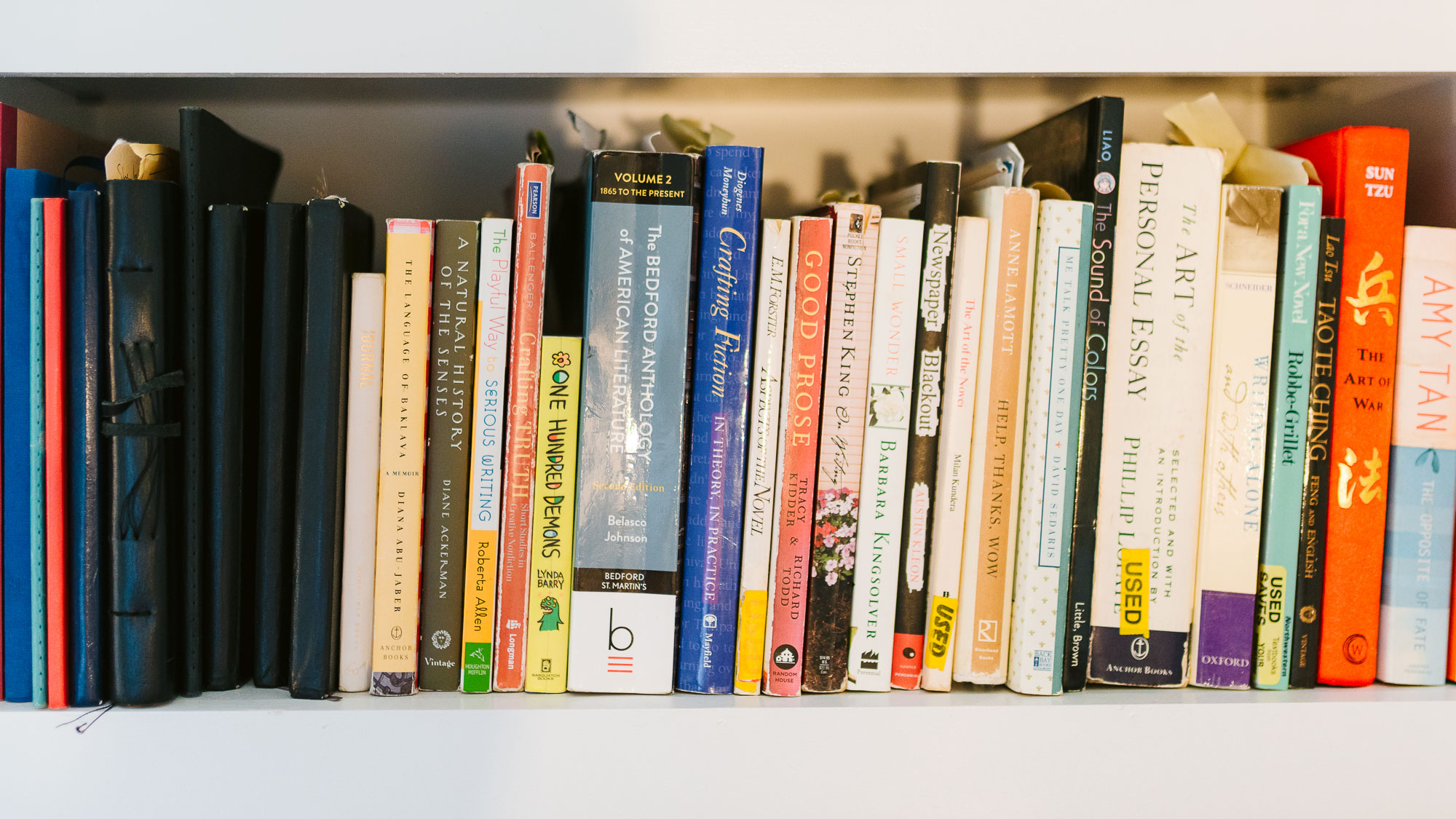

I think my writer friends and students need a little convincing about revision–I teach the creative writing nonfiction workshop at the College of Western Idaho. Revision, or rewriting, has been a chore in the past, something to finish your final portfolio for the semester. But with creative nonfiction, you get to go back, revisit a moment with the wisdom of time passing, and ask yourself, “What am I trying to figure out about what happened?” You’re writing to figure out what you don’t know about what you know; to find the story you’re trying to uncover. What’s the language you’re going to use, the carnal, the sensory details? And how to find the emotional truth of the moment so somebody reading it can feel the way you did. First drafts–you’re just showing up.

The first draft is just getting it out?

Yeah. And inviting everybody in. It’s through revision that you find out, “Oh, I thought the story was this, but really it’s this.”

The undertone sometimes becomes the theme?

Oh, yeah. That’s what I love. I love teaching the narrative braid.

What is the narrative braid?

Lidia Yuknavitch, a writer I love, wrote The Chronology of Water: A Memoir. Over the pandemic, she taught Zoom writing workshops. The first workshop I took was her narrative braid. And I was obsessed. It’s a way to think about the construction of a story that isn’t linear. At the time, I was working on an essay that I ended up doing a reading of at the 20th anniversary of the Boise State MFA program. March 13th 2020. Right before BSU shut down. You know, we walked out of the Hemingway Center, and BSU closed.

Yes, I remember.

I remember having a glass of champagne with friends after the reading, and something was happening. The energy, the crackle in the air just felt different. Josh said, “I feel like if I opened the door and saw a spaceship landing and aliens walking out, I wouldn’t be surprised.”

It did feel like that. It felt like the end of an era, which it was.

It was. That reading was the last night in an old world. In that essay, I was braiding together grief, my dad, and the island of Kaho’olawe, which is an uninhabited Hawaiian island, where two years earlier, we had taken my dad, thinking maybe it could heal him.

We spoke earlier about how he passed away from cancer, after, I’m going to say, dodging it for nine years.

He kept beating it. He kept coming back–

How did you approach that theme?

Lidia Yuknavitch teaches that you start with a memory. You go back in your mind, or physically, if you can, to an environment, or a place. The place I started thinking about was Kaho’olawe. The second is a memory or a literal thing connected to that place. The third is writing in another language such as a medical language, or table of contents language, or folk tale, fairytale language.

You use a contrasting tone that adds meaning to your story?

I was using Hawaiian myth about this particular spot of ocean between the island of Maui and the island of Kaho’olawe. Kaho’olawe, when I think about it, is a beautiful Hawaiian, spiritual place, and it’s special to my family. We did a service trip there.

So your different braids are–

Kaho’olwae, the idea of healing, water, grief, Hawaiian myth. The through line is love and how to navigate. Both grief and ocean.

There’s a journey there.

The ocean as a place of healing. We also scattered my dad’s ashes there.

That’s duality, right?

It’s an interesting way to think about constructing a story, to fit in the things you’re obsessed and haunted by. I would come up here, write, and listen to Hawaiian music to get myself back into that place. And bringing my dad back into this room. It was one of my favorite writing experiences. And it was such a great reading. Then everything changed.

Yes it did. What’s the title?

“All the Places Where I Prayed for a Miracle.”

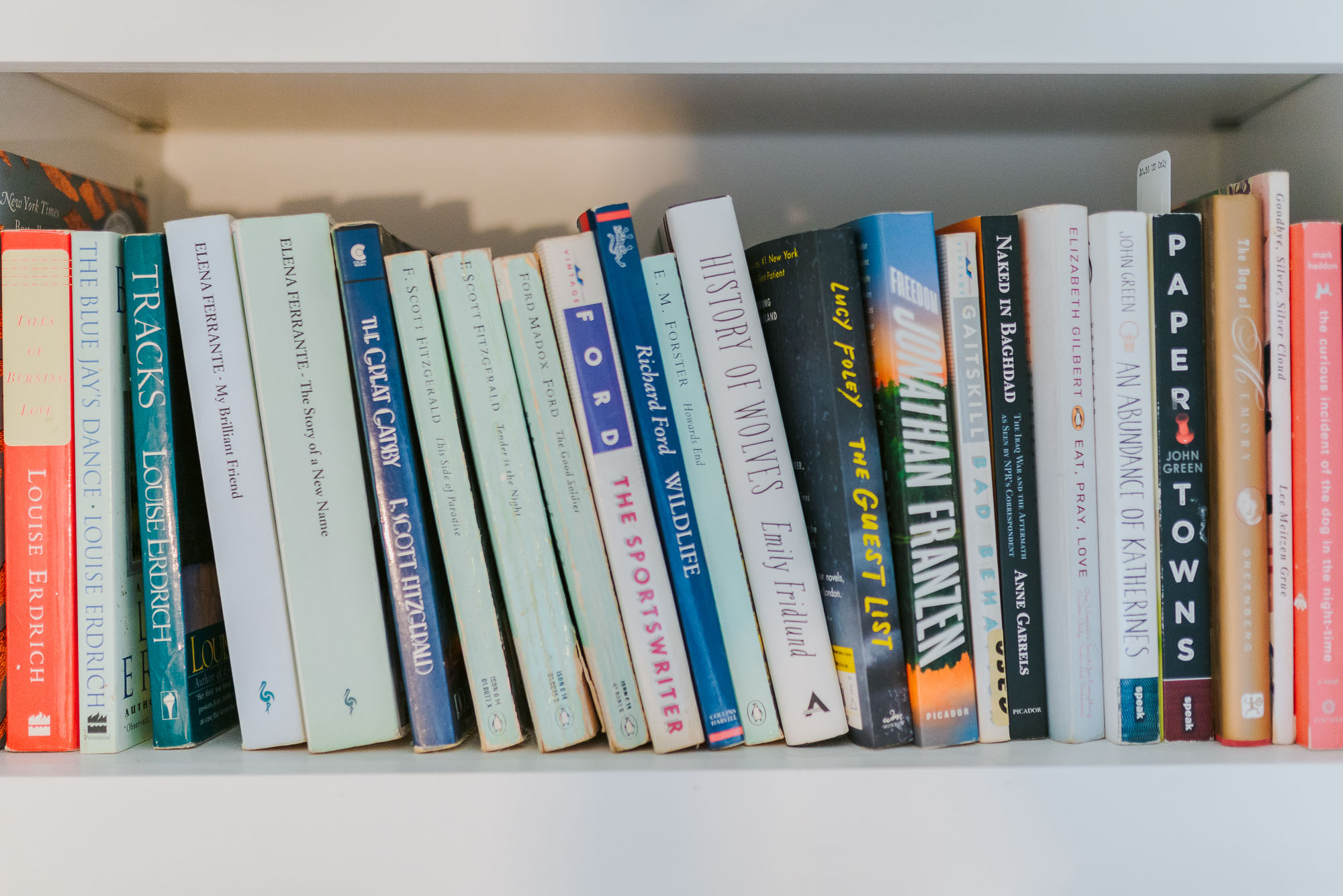

You do a certain number of pages in the morning?

Oh, morning pages, which is from this book everybody was reading when I was in graduate school in Hawaii in the ’90s, called, The Artist’s Way, by Julia Cameron. It’s great. I love the habit of it. I wake up a little before 6:00 and try and get three pages. There’s something about the intention‑setting of morning pages that I find helpful. Sometimes I use them to navigate a stuckness in a piece I’m working on, a way out of something I’m not sure about. I’ll use morning pages to write a scene in an essay I’m working on, or to bear the weight of something I’m thinking about. When I get them down on the page, I don’t have to spend time thinking about it, and I can think about something else.

You don’t have to hold it inside because it’s now being held externally. You can release that energy, let it flow, because it’s not–

It’s not stuck in there.

Good stuff. Which Island did you live on?

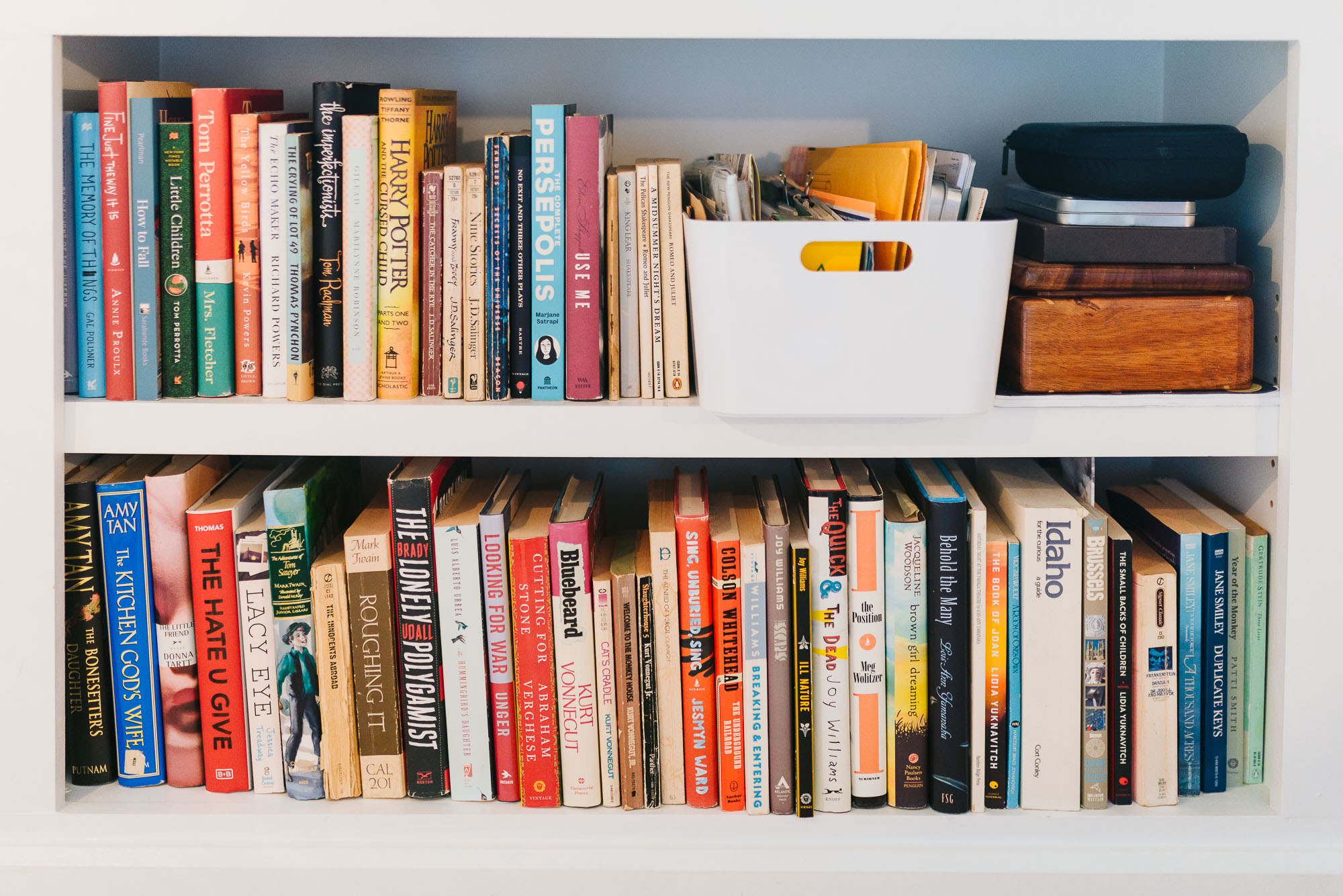

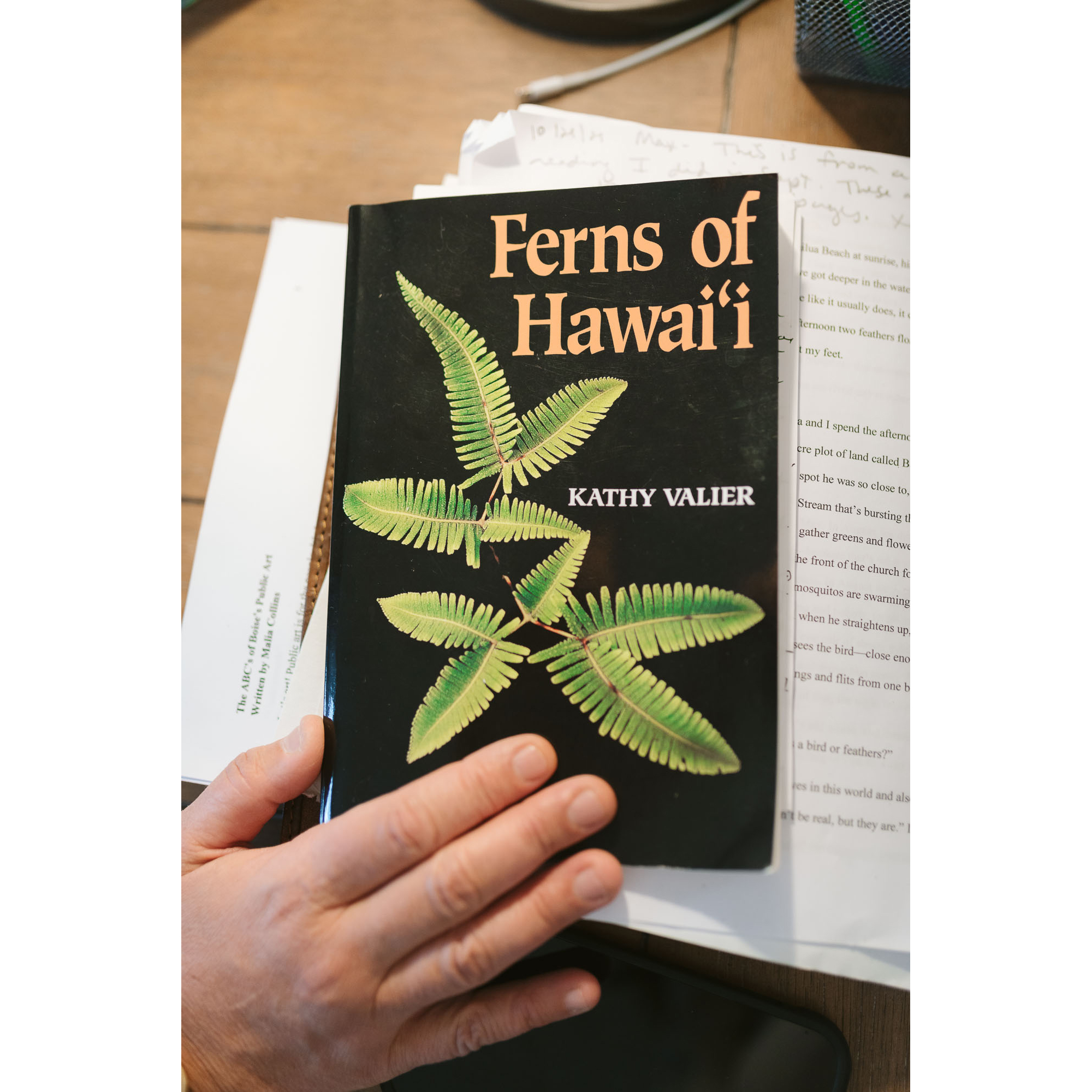

I grew up in Kailua, on the east side of Oahu. We lived in Maunawili, which is a valley; you come through the Pali tunnels to the windward side of the island. It’s in the Ko’olau Mountains. My dad loved picking; my mom worked at her friend’s flower shop, Auntie Barbara. So we would go back into the mountains behind the house where I grew up, and go picking for palapalai fern, for laua’e fern to make lei. After my dad died, I got really interested in feathers and birds and ferns. I liked picking because I liked hanging out with my dad. There were five kids, and I was the only kid who wanted to go. My dad was always busy; there was something about those outings because I had his full attention. And it was beautiful. My favorite thing to do in Hawaii is to go hiking. When I’m here, Boise, I miss the ocean; but when I’m there, I like being in the mountains.

Isn’t that funny?

I grew up in Hawaii, but went to Wisconsin for college. It was the farthest my parents would let me go. After college, my boyfriend and I, who is now my husband, moved to France for a year.

How did you come about that?

We were romantics. We lived in Paris, but couldn’t find jobs anywhere. Then we found jobs at the Chicago Pizza Pie Factory, which was this cheeseball restaurant on the Champs‑Élysées. I thought “This is a sweet location.” But they said, “No, no. This one’s in the South of France. Can you move”?

So you went to work in an American‑themed restaurant?

Yeah. We had our first training at the McDonald’s in a strip mall–I had thought we were going to get these interesting jobs in Paris. [laugher] I went through six rounds of interviews; Josh was with me and when he walked in, they’re all, “He looks like an American barman.” He got hired on the spot.

But you went through six rounds? Did you not look American enough for them? Born and raised in Hawaii–

Native Hawaiian. I guess I wasn’t interesting enough or something.

What does it mean to be a Native Hawaiian?

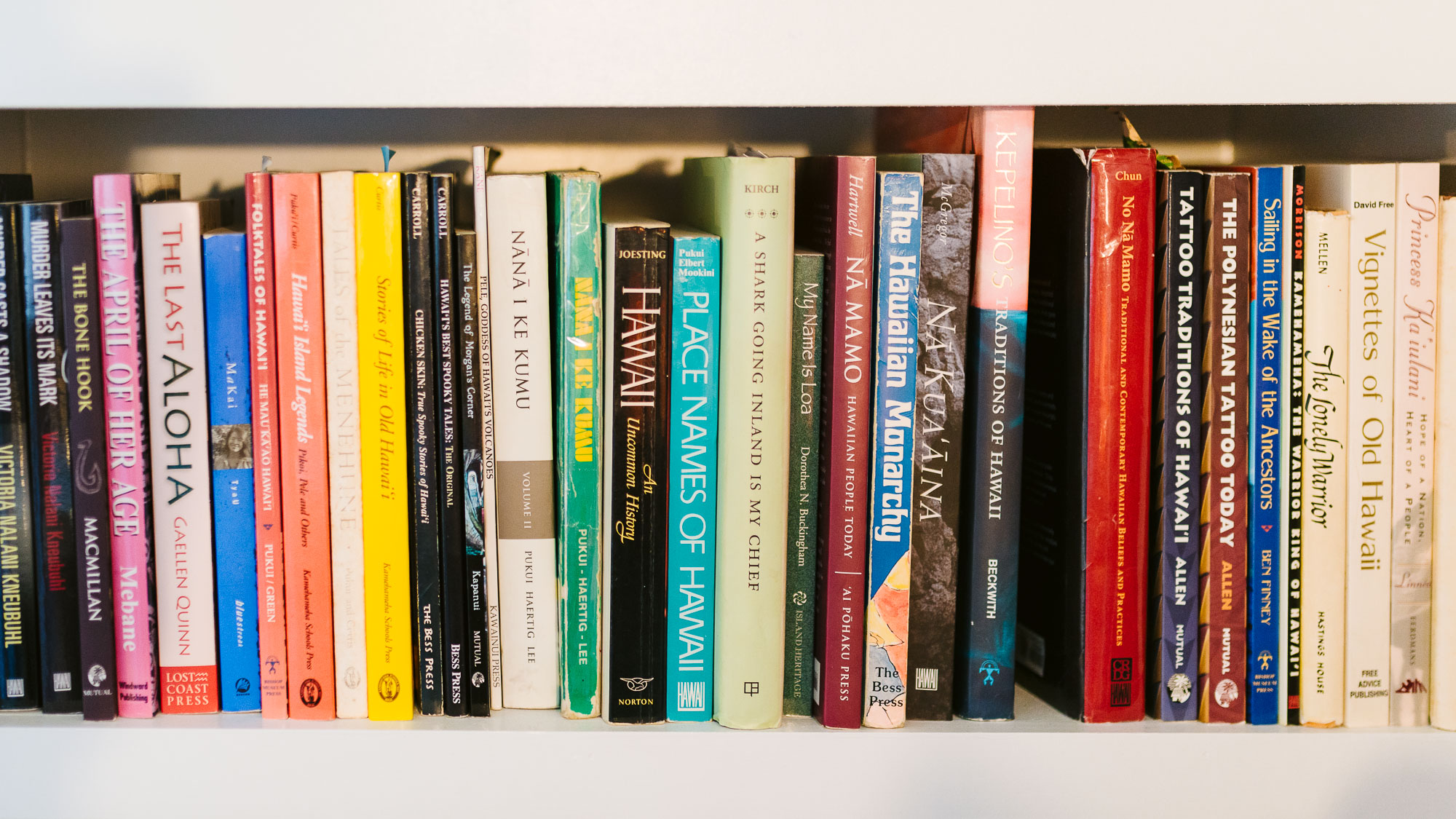

That’s a complicated thing I’m always straddling. Hawaii is home to me. When I think how I navigate the world, it’s as a Native Hawaiian. I have really tried to instill that sense of pride and culture in my kids. We went home every summer and they did summer school there.

What kind of summer school?

Kamehameha School; you have to be a Native Hawaiian to attend. My grandmother was full Hawaiian, my mom’s half Hawaiian, I’m a quarter Hawaiian, and the kids are an eighth. You have to show your blood [line] to get in. It took six months to prove it, even though I graduated from that same school. It was a lot of work. But then they took classes in celestial navigation, Hawaiian language, culture.

What was it like to attend college on the mainland?

Wherever we traveled, everybody knew where Hawaii was and there’s this mythology–something instantly interesting about me when I introduced myself, “I’m Malia, I’m Hawaiian,” and Josh, who’s from Missouri–in France, half the time they’d call him George; they’d say, “Oh, Missouri, you like ketchup,” I mean, that was their thing. But Hawaii! Hawaii, they wanted to go visit, they’d seen pictures. For me, there was an ease navigating the world with this idea of Hawaii. But Hawaii. It’s so different from that idea.

You encountered a different kind of myth?

People think beautiful oceans, waterfalls, hula dancing, drinks in a pineapple, or whatever. That’s the idea that was sold; Hawaii, the tourist destination. It’s such a colonized way to think about Hawaii. During the ’70s Hawaiian Renaissance, there was renewed pride in what it meant to speak Hawaiian, to dance hula, and the importance of having schools with the entire day taught in Hawaiian language.

Full immersion?

Yes. Many people speak fluent Hawaiian now. When the missionaries came to Hawaii in the 1820s, the Hawaiian language was forbidden. It went underground. My mom, born in the ‘40’s, had to have a white name.

Did she have two names?

Daisy Lee, that was her white name. Her Hawaiian name is Aloha. She said growing up, she would hear my grandparents whispering to each other in Hawaiian.

It was not acceptable?

Because what mattered was speaking English–assimilation. In the ’70s, they’re like “Hold up, the Hawaiian culture is dying. Young people don’t know the stories and ways of being.” For instance, the Hokulea canoe, this poster on the wall, is an image of going back to Polynesian way. The Hokulea went from Oahu to Tahiti following the same route using celestial navigation and by currents without a compass or sexton. These were the traditions they wanted to revitalize that were being lost.

You want your kids to know the responsibility of being Native Hawaiian. What does that mean?

I think a lot about understanding what it means to be a contemporary Hawaiian and the connection to place and community. I love that Max is a mathematician because Hawaiians were so curious, and interested in the stars, and ocean currents, and connected to the land; they used to have the ahupua`a system, where people who lived in the mountains took care of the birds and tended to the trees, for instance.

The geography of your home meant you had certain duties?

Yes, pre-contact Hawaii. There’s this Hawaiian word: kuleana, which means sacred responsibility. My kids, growing up in Boise being Hawaiian, thinking what’s their Kuleana to this place? There’s a connection between the past and future that I see the kids embodying that’s so Hawaiian to me. The understanding of where they came from and the understanding of their responsibility to tend to this place, to tend to this earth, to tend to the natural world, to tend to what it means to be a community, what it means to be a family, so their descendants can see this place and the things we love inside of it. That sensibility also carries here.

Carried inside?

It’s the aloha spirit. Also, what it means to carry all those stories and ideas and curiosities and wonders that came before them, are embodied inside them, wherever they are. It’s what keeps them anchored to the world.

Beautiful. Tell me about your project with refugees here in Idaho.

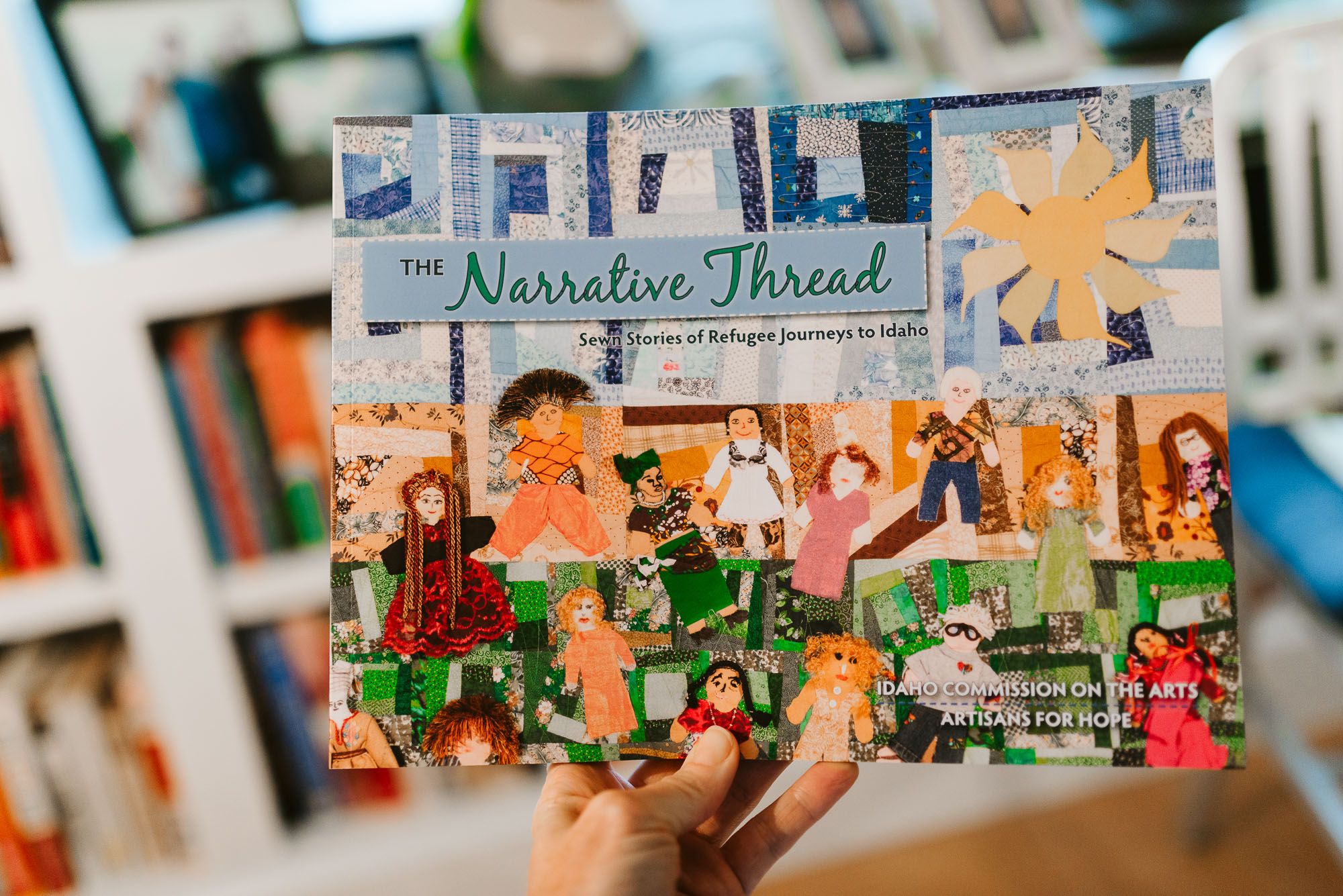

It’s a printed version of a story quilt project in partnership with the Idaho Commission on the Arts and Artisans For Hope. This beautiful book just came out this fall. The story quilt project started back in 2011. Maria Carmen is a folklorist at the Idaho Commission on the Arts. One day we were talking, I said, “I love when my students write, but I wish we had something visual, too.” She suggested a story quilt. We met at the old Artisans For Hope, which was across from Flying M, and pitched the idea, and they said that sounds great. So we got started; I would go in once a week, and ask questions–

Of Refugees?

Yes, mostly women, but of women and men who were working at Artisans For Hope making things to sell. I’d go in every weekend, ask questions, and write down their stories. I was the scribe; there was one woman who said, “I’ll only tell you my story if I can tell it in French.”

Deal.

Exactly. I said, I can speak French. I think she was like, “Oh!”

She thought she would avoid it. It was scary for her.

Stories are hard. Here I am coming in, with my notebook and my pen and–

Kind of like me coming to you–

Yeah. But they kept seeing me every weekend. People who didn’t want to tell a story at first, saw me coming back, and watched others tell their stories. The stories are beautiful, they’re heartbreaking, they’re hopeful, and they’re rooted in resilience.

What are some of their experiences?

They would tell a story from the country that they left, stories of life in transition, stories of Boise. Then they would choose an image that resonated for them and turn that image into a quilt. The quilts are unbelievable. They’ve traveled around the state, across the country even.

They’ve been on display. They resonate with the viewer.

What I love so much is the connection when we know each other’s stories, it opens the world up and you start to understand the importance of recognizing each other’s full humanity. It’s about going deeper than the surface.

My last question for you is about bliss, what does it mean to you?

You know–oh, bliss is so complicated. Gosh, I used to be so hopeful. But, something I always want to feel regardless of where I am, is a feeling of surprise, something unexpected, and to find joy, bliss in that. Last night, talking to Max on the phone, his voice–I mean, sitting on the couch where we’d all sat together as a family, there was something about his voice showing up in this space–I felt joy in that moment.

You must miss him very much. It’s not easy sending kids off to college.

It’s not. Sometimes, when I’m writing I have a feeling, I go back and look at a sentence and don’t remember having written it. That’s something unexpected or surprising to me. Or watering my ferns in the morning. The ferns make me feel joyful, connected. When I was growing up, my dad loved coming home and watering his bird‑nest ferns. And I water my bird‑nest fern, and I think, this is how I’m transcending time, this gesture that I learned from him, tending, caring for, noticing things, and paying attention.

Maybe that’s where my bliss comes from; it’s from paying attention. It’s from hearing and it’s from smelling and noticing. Even the sound of Josh walking down the stairs is such an ordinary sound, but how desperate if I didn’t hear it. That’s what I have to bring myself back to, the things that feel so ordinary, the breath, the footsteps. I mean, that’s blissful.

North End

December 15, 2021

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.