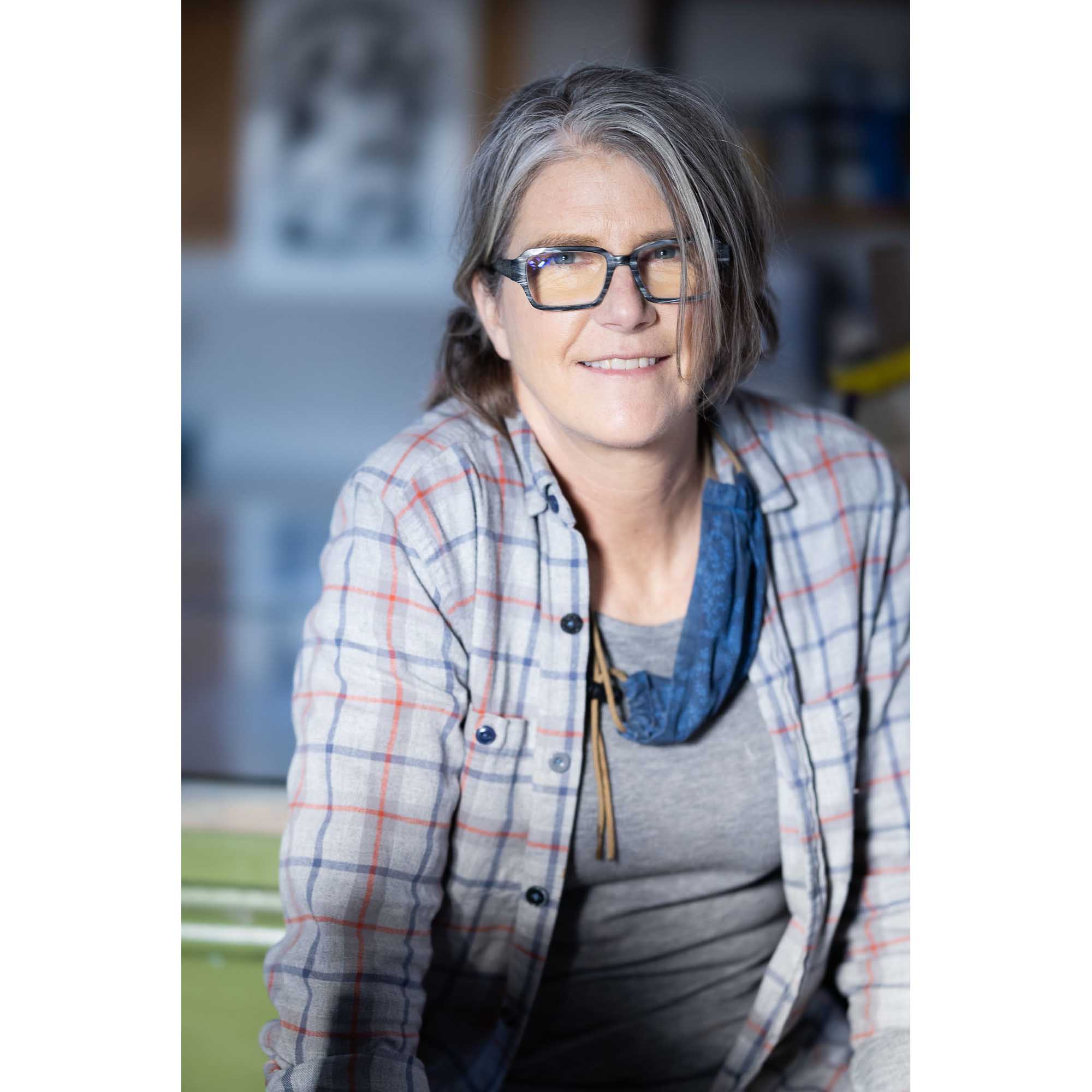

Creators, Makers, & Doers: Wendy Blickenstaff

Posted on 3/3/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Wendy Blickenstaff had recently returned to higher education, earning a second degree in the fine arts; her first career focused on plein air painting. Early in 2020, she set up a printmaking studio with big goals for that first year, but a world in the beginning stages of a global pandemic had other plans. Wendy describes those early days of sheltering-in-place and of having a feeling of helplessness, but an even greater desire to send a message: “Hang in there.” In a guerrilla-art, anonymous act, she hung Virtual Hugs, small prints made on leftover fabric, around her neighborhood. The encouraging results have propelled her further on a journey towards making art that engages in tough subjects and resonates on an emotional level. Wendy feels an ability to empathize with those who would call themselves an underdog, something she’s familiar with after being misdiagnosed as dyslexic for much of her life. The biggest lesson? Sonder, a word that means everyone has a unique, complex life. Wendy came to understand this deeply while volunteering with a local homeless shelter. Looking back, she wouldn’t change a thing, even if her 2020 plans went awry. Lemons into lemonade.

You earned a degree from Boise State in printmaking and you had certain goals in mind. How did the pandemic change that?

You earned a degree from Boise State in printmaking and you had certain goals in mind. How did the pandemic change that?

2020 was the inaugural year of my art studio. I’d purchased expensive printmaking equipment and I had shows lined up for the year. As information about the virus started to unfold and Boise went into lockdown, I realized things were going to be different.

Did you have a business plan in mind?

I did. I used to do landscape paintings. You’d make a painting, sell a painting, that’s the way business goes; share it, show in galleries. With printmaking, it’s fun because you can make multiple prints; I don’t have to charge as much. I was going to do the Farmers Market, Art in the Park, things like that.

Printmaking has been called a democratic medium.

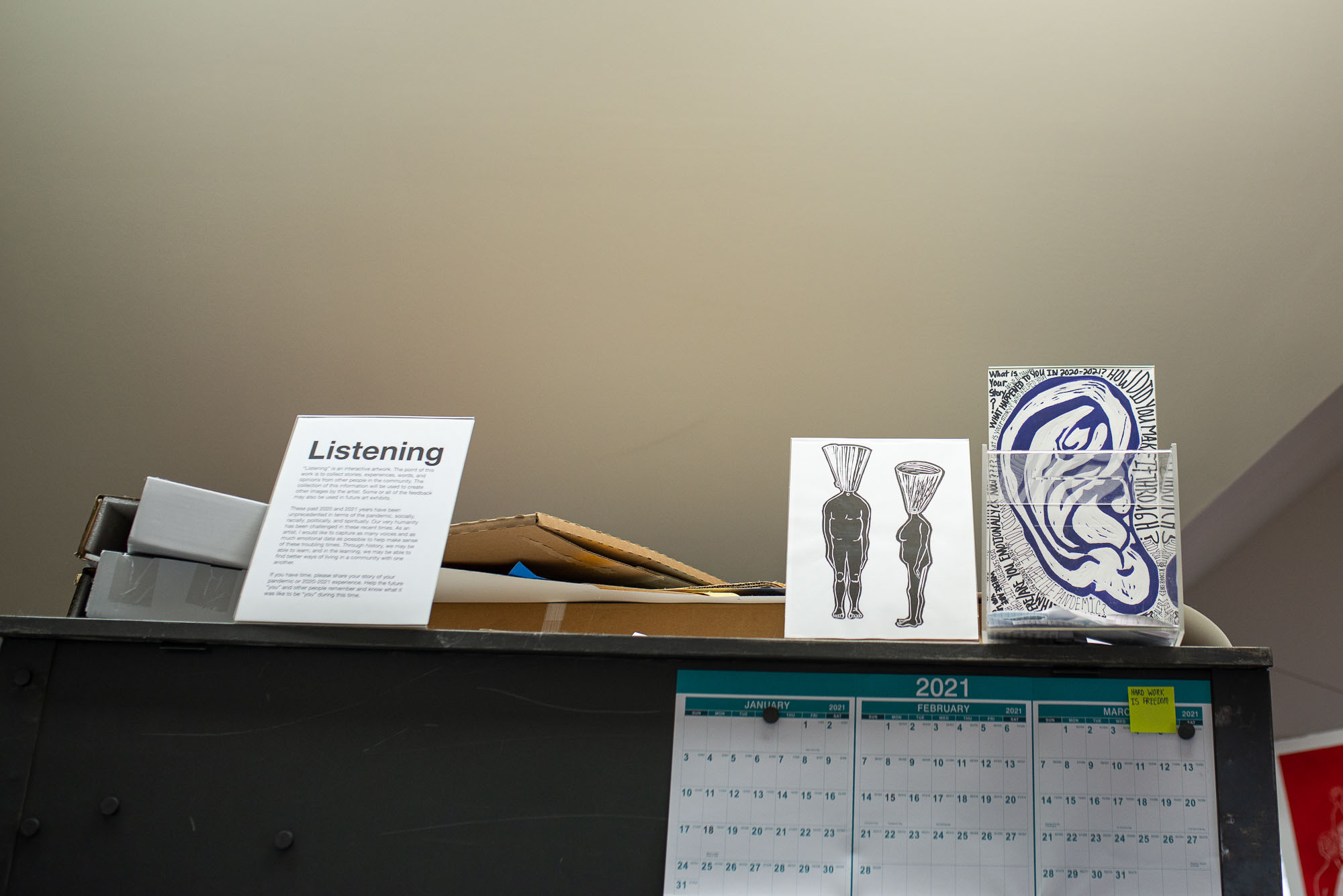

It makes the art accessible to more people. My plan was to do psychological prints about emotions. I’d been doing therapy, personally, and found it interesting for figurative work, to pivot toward emotions. When COVID came, especially the first couple of weeks, it was so heavy. I felt helpless; I’m an artist, I’m not an essential worker. I felt like there was nothing I could do to help; I needed an outlet. If I’m sitting in my art studio making art, and nobody sees it, is it really art? I seem to have a need to share my work.

That was a problematic time to share work, everything was cancelled at first.

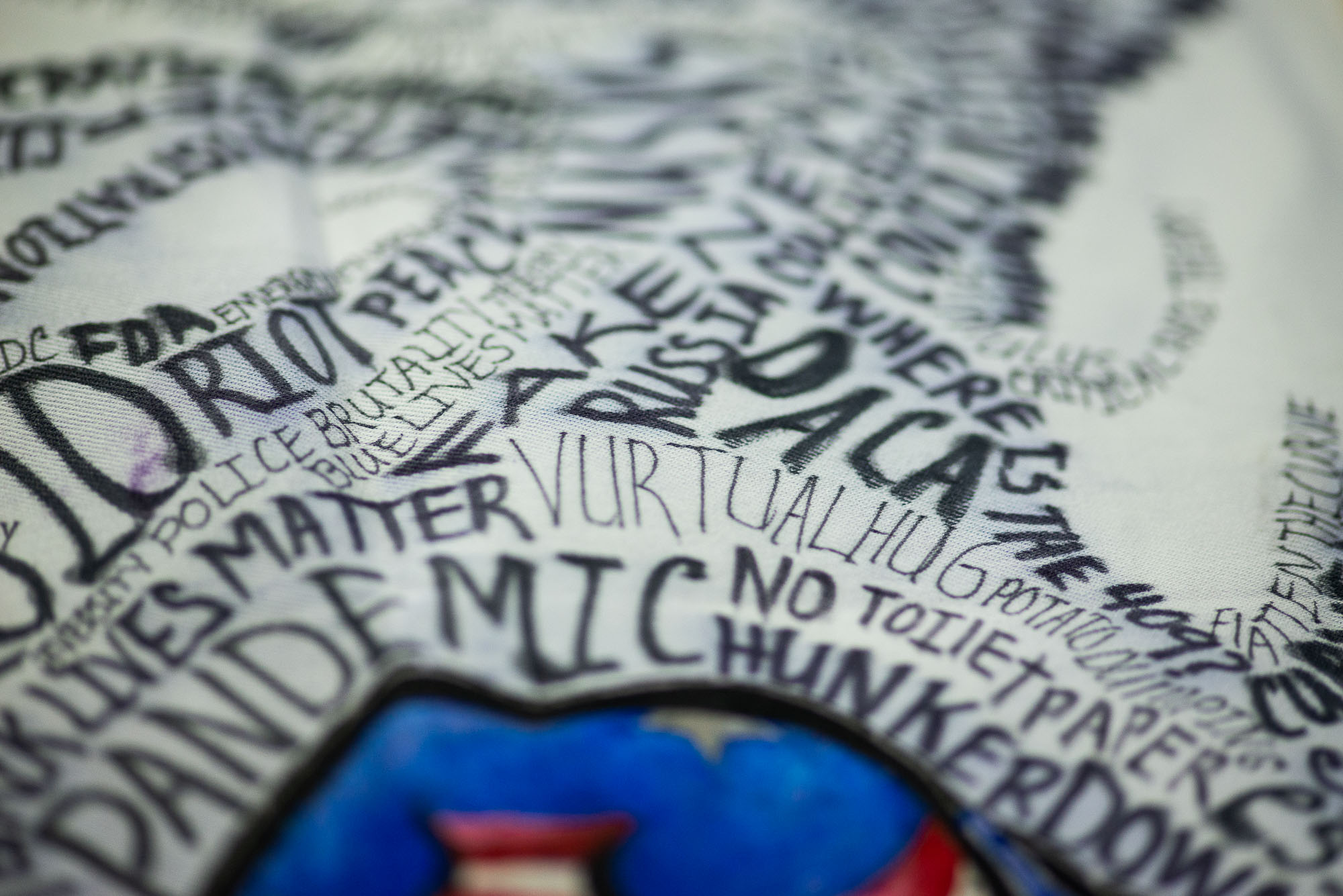

We were all locked down. That whole spring, it was like you were waving to people from across the street, and somehow that felt risky. It was kind of kooky. I wanted to be able to share my artwork and the only way I figured how to do it is—I had some fabric inks, so I started printmaking on extra fabric: old bed sheets, scraps, my husband’s old dress shirts, just anything, and I started printing hopeful images, to encourage my neighbors and the people around me not to be scared, like I was, and to hang in there.

What did you do with the prints?

My first set, I call them Virtual Hugs, just little images—I got up early, like 5:30, when it was still dark, snuck out the door with a stapler and stapled them onto telephone poles.

In your neighborhood?

Yes, in the alleys, because I thought, “Whoa, I could get arrested for this.” I’m a rule follower. [laughter] So I started hanging these little Virtual Hugs up all over the neighborhood. And, I kind of felt better.

Sometimes artists say they make work for themselves and the viewer is not important, that the satisfaction is in making the art. But for you, is it in the sharing?

I feel it’s more satisfying when interaction happens; when you’ve made somebody think or helped them. I’m a big one for trying to do good. I was imagining somebody out walking their dog, feeling frightened, and coming upon this little image, a Virtual Hug, and it might make them feel better, like, “Hey, there’s good out in the world.” A random, weird, good thing.

What kind of response did you get?

Well, the Virtual Hugs were the first week. The second week I made another image, and the next week another. I kept hanging prints up on different telephone poles, getting a little bolder about my placement. It was like guerilla art. By the third week, I noticed people had started posting pictures of the work on social media. It was fun because I didn’t sign my name on them. I just kept making images.

It was anonymous. You’re an art bandit! Did you get arrested? [laughter]

I did not get arrested. But later in the spring, somebody outed me.

You have a very particular style.

I do. Somebody from “Idaho Matters” [radio program] got a hold of me so I did an interview on Boise State Public Radio. I was really outed after that.

How exciting! Did people take the prints down?

It was really crazy; hardly anyone took the pieces down. In June, when we started to move out of the lockdown, I felt the art had served its purpose. I didn’t want it to be a burden or obnoxious, so I posted on any site I could that people were welcome to take the pieces if they wanted them. I was a little nervous. What if people don’t take them down? That would be bad news for me. But within two days, out of the 70 pieces, I ended up with only three or four left. That was exciting.

This wasn’t part of your original business plan?

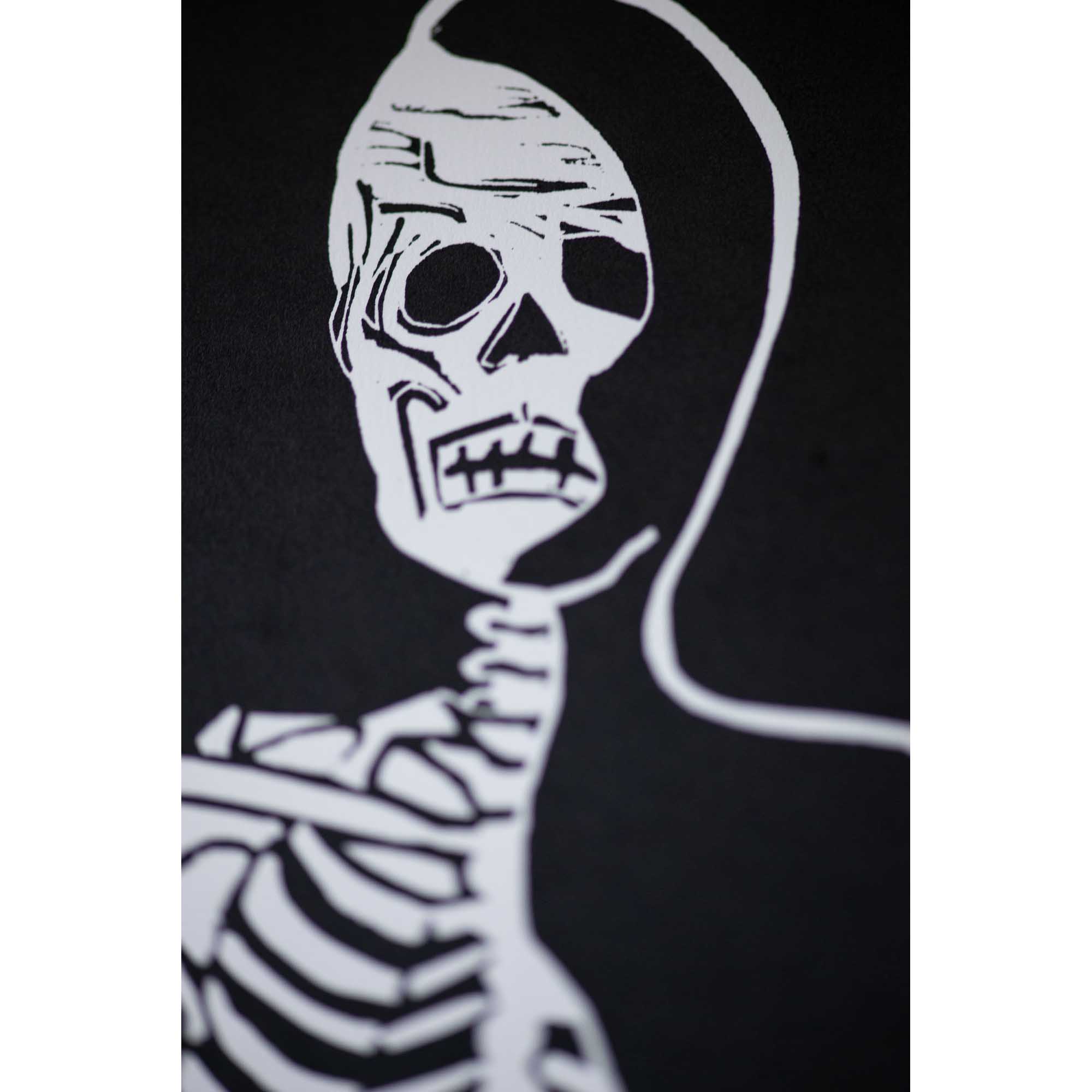

No, but it helped me define why I’m doing art and it helped me define who I am, and that felt right. Most of my figures are bald, they have no facial features, they don’t have a gender. Because it doesn’t matter. All people [experience] sadness, so why put a gender on that? It doesn’t matter what race you are or how you identify sexually, people are sad, people get depressed, people are happy, people need encouragement.

You gave away a lot of prints, did that result in any sales?

I feel like people have to get used to an image in order to become interested in making a purchase, to then say, “Hey, that’s a “Blick” and I’d like to purchase it.”

Repeated exposure leads to visualization which leads to a purchase?

I’m hoping. I set up an art drop-box for COVID.

The drop-box is a way to deliver art?

You look on my website, find something you like, mail money, then I seal it up, put it in the drop-box, and give you the combination. I did make some sales that way.

Tell me about the transition from making landscape paintings to these stylized figures, and printmaking.

When I was doing the plein air painting, I was also working as an art teacher and it was stressful for me. I couldn’t take on society’s problems in my art. I used art to relax; I wanted to make something beautiful and calm and to celebrate God’s creation, that’s why I made the landscape paintings.

It allowed you a calming space?

It had that purpose for me. When my kids went off to college, I returned to school for an art education degree. At Boise State University, you have to take a printmaking class as part of art education. Actually, at first, I found printmaking kind of annoying because there are so many steps to get one print. You have to draw it, carve it, print it with ink. It was so tedious. But by my second class I was excited because I wanted to make figurative art about people and about emotions and feelings and intellectual ideas. I’d been painting for so many years, but felt I couldn’t do contemporary subject matter with that. Every time I tried to do some sort of contemporary painting, it felt wrong. When I started printmaking, it was so different that I was able to sever that part and start making contemporary images about human struggles.

That shift allowed you freedom?

It did. It was really like a rebirth, a new way of making. I went with BSU to Venice for a summer, which was amazing. That experience has had a lot of influence on me, opening my mind to possibilities; what art is and what images can do. In Venice, they have the Biennale every two years and there were a couple pieces that just left me sobbing. Faust [Anne Imhof] was the name of one, it was an entire building and floor made of glass, with actors performing avant-garde exercises and interacting with each other on a human level inside.

There were probably 16 actors. Sometimes, they had props or they’d be crawling under the floor or moving almost like ballet. Every performance was different; it was improv. I think the biggest problem I had, was when it looked like [an actor] was being harassed or, forced to do things they didn’t want to do by another actor.

There was a lot of tension and power dynamics being acted out?

I was standing looking through the glass wall at the—I’m going to tear up even just describing this—at the actors and they had this wet piece of cloth. The actor who had been demeaned turned around, and it looked like he was looking directly at me, and he threw the piece of wet fabric so it hit the glass right in front of my face. For me, I felt ashamed that I had let something happen that was inappropriate. The guilt of being a bystander to an injustice.

Particularly because he had acknowledged you?

Part of my art is that I don’t want to be a bystander to injustice, I want to be someone who tries to make it better. Even if I don’t, at least I know I left everything on track to improve communication or improve a situation, or society; that’s why I volunteer at the shelter. Looking back at that experience, was like, “Wow, art can change people.”

How did it change you?

I realized how powerful art can be. Yes, the landscape paintings are beautiful and celebrate something beautiful, but, I can actually shift or pivot someone towards a better understanding through art. Right now, I’m able to put more energy into the world around me and engage in harder, tougher subjects; to think deeply about people’s problems, including my own. I think part of doing all this figurative work, working in the shelter, and working towards diversity and inclusion in the different organizations I belong to, is me trying to understand how we can get along. How this all works in a complicated society.

What are you doing at the shelter?

I started working at the Interfaith Sanctuary shelter in 2020. I was wondering why and how someone would become homeless. When the pandemic started, I’d done an image of a figure huddled in their house and it really struck me, “Gosh, I’m, like, scared to death, huddled in my house. What if I didn’t have a house to huddle in?” I hung some of my prints down by the shelter, but it felt awkward, like I was trying to reach a population I knew nothing about.

That you were coming from the outside?

I thought that was inappropriate. So, I called Jodi Petersen and asked if I could do art with the residents. Later, I realized that’d I had a preconceived idea about how I was going to swoop in and teach the residents. Luckily, I kept my mouth shut enough to understand that was not what was going to happen.

Were you scared?

I was really scared. Sometimes, I’ve had good interactions, and sometimes I’ve had bad, you know, you hand a buck here or there. I didn’t know what to expect.

It’s an unknown.

They have a program called Project WellBeing. Nicki Vogul runs it. She stayed with me while I brought printmaking supplies in and I said, “Would you guys be interested in making some art?” I discovered that there are a lot of creative people there and that what they need is someone to listen and to have access to supplies. They need that much more than they need somebody telling them what to do.

To give time, material, and attention?

It’s more helpful than me coming in and doing some tutorial. To have space and time set aside, to put music on and just have jam time, talking with friends and making something creative. Some of the residents hadn’t done anything artistic for 20 years or so. The other thing I realized from listening, is that a lot of residents have been to college. They have families. They were cheerleaders, or soccer players, but then they got Huntington’s disease, or their family is no longer available, or they have no more lifelines left because they’d made some bad decisions and burned all their bridges. But that they all are individuals with active lives. It reminds me of the word sonder, which isn’t quite in the dictionary yet, but it means that every person has a unique and complex life. You can’t stereotype them.

Everyone has a complex story.

Working in the shelter has been humbling. I now think of my images as woven within a complicated society. I think that was spurred from interacting with people outside my regular realm.

You put yourself into a new context, and it stirs up new ideas and connections?

It never occurred to me that women in prison are crocheting and that crocheting is a manual meditation. Somebody once told me that crocheting saved their life. I’m now in charge of the art collective at Interfaith Sanctuary. People come through who are artistic and want to do something professionally with their artistic talents, so I try to give any knowledge that might help.

You went in with a question—why are some people homeless? Did you come up with an answer?

I came up with the answer that a lot of us could be homeless at any moment; that the people in the homeless shelter are just like people living in homes. That some of them have undiagnosed mental problems, or have burnt all their bridges. They have run out of normal resources. Most of the residents at Interfaith Sanctuary have committed to doing programming or going to drug rehab. The shelter helps set them up with Medicaid and Medicare. They get job training, earn money, open a bank account, and then CATCH Idaho works with them to find housing. Today, they were celebrating; one of the residents finally earned enough money and has a job and he’s moving out. He could not reunite with his daughter until he had an apartment.

That’s a big day!

It’s a big day. Those kinds of things are happening in that shelter all the time.

Has there ever been a time when you needed help?

Absolutely. I’ve done some EMDR therapy (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.) I’m hoping some of my images can be incorporated into EMDR therapy. My business plan is for my images to be used by therapists, that’s where I’m headed.

When people are not able to verbalize a feeling, they could look at art as a starting point for expression?

Yes, as a tool, “I can’t describe what I’m feeling, but this is what it looks like.” It’s too late for me to learn how to be a therapist.

Do you want to be a therapist?

If I knew in my 20’s what I know now, I would have gone through all the psychology classes; still do art, but I would have been a therapist. When I was young, I was diagnosed with dyslexia, so reading was not my strong point. Art was a way for me to express myself without reading or writing. When I was 40, my daughter, who is very intelligent, was diagnosed with an eye-tracking problem. When I went in about the same time to get glasses, we realized that I didn’t have dyslexia; I had an eye-tracking problem too.

That must have come as a surprise.

Since then, I’ve realized I can write; I’m actually a really good writer.

That is life-changing!

Life-changing! I’m super capable at reading. I went from reading books to go to sleep, to reading voraciously. When you have an eye-tracking problem, you read really slowly, so it puts you to sleep.

How do you correct eye-tracking?

My daughter is young enough she was able to do physical therapy, I was too old to get my eyes retrained, but by getting a pair of glasses, it forced my eyes to track properly. It fixed my problem. I relate to people who are having problems because I feel like an underdog. I feel like half my life I’ve tricked people into thinking I was smart, because I had this reading and writing problem.

Did you feel like an imposter?

Yeah, like a phony. But you look at life—if I wasn’t forced to communicate through images, I wouldn’t be this type of artist. I’ve spent my whole life trying to communicate through images, and to be given the gift, at 40, to be able to read and write—it’s amazing. I just feel so young. In 2019, I went back and took English 101 with my daughter at Prescott College. For the final paper, out of, I don’t know, fifty students at least, two students got a perfect score, only two. And I was one of them.

So gratifying! You couldn’t have done that before.

Vindicated, right? I have so much more confidence in communicating.

What I’m hearing is that perhaps you would have studied psychology, except you had this problem with reading and writing that kept you firmly in the visual arts. You felt like, “If I could go back I would…” but then you wouldn’t be where you’re at now either. “What if?” That’s the eternal question.

I think I can be more helpful as a human being on this earth in present form. I made lemonade out of lemons. I’m really happy where I am.

That’s pretty amazing. Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

Optimist, for sure. If I ever lost hope, I’d be dead. I don’t think you can ever give up on any person, thing, or country. There’s always hope. I don’t know if that’s part of my spirituality, I’m a Christian. I just think my light would go out if I didn’t have hope.

Have you ever been described as ultra-productive?

Yeah. [Laughing]

You’re laughing.

I have way too much going on. I think it stems from having a disability as a kid. I thought if I kept working when everybody else was still, I could keep up.

Compensate?

I feel happy when I’m constantly busy, having all sorts of excitement. I’m a little addicted to having things to look forward to.

You like momentum?

I’m addicted to momentum.

Me too. It feels good.

I keep longing for things to be calm, but I notice any spare moment I have I’m like, “What about this…”

Do you ever get tired?

I have so much adrenaline and energy getting projects going, and when it’s done, I’m pretty wiped. [Laughing]

Can you list all your irons in the fire? Because there’s a lot.

In 2020, I did the outdoor Greenbelt show, which I called the 2020 Art Experience; I want people to experience it, not just to look at it. Those pieces were hung on trees along the Greenbelt all the way from Main Street to Quinn’s pond. Actually, that was the second thing. The first thing was the prints on telephone poles in the North End.

The Virtual hugs.

Then I froze water in giant heart shapes and a bunch of friends and I hiked into the foothills and put them on Camel’s Back trails; all over the foothills. Then they melted. I didn’t want to ruin the environment and I didn’t want to get arrested. [Laughing.] Very important not to get arrested.

That spring I did a mural on Overland road called Pins Out with Reconnection Mural Project, 2020 hosted by Talor Coe from Sector Seventeen.

Next, I did a large quilted piece that hung on a building in Twin Falls for the Art and Soul of the Magic Valley 2021.

Then together with a friend, I helped to start the Turning Pages art and literature program with Collister United Methodist Church’s Racial Justice Team.

Then the Art Collective at Interfaith Sanctuary.

I’m doing a mural now in the Collister United Methodist Church, a collaboration with Laura James. She’s a person of color artist in New York City. Here in Boise we have a Swahili refugee community and the Collister United Methodist Church has a Swahili service.

Then I started an internship program at BOSCO (Boise Open Studios) with college students.

I had my own intern start a program called Capture—capturing stories of the 2020 pandemic period.

I’m working on a psychology book with Vashti Summervill.

You just listed eleven things in less than two years.

A lot of those things happened because I just am so wounded by what’s happening. This is me trying to help out.

Has the process been helpful for you?

It has. It’s made me feel useful.

North End

March 3, 2022

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.