Creators, Makers, & Doers: Tania Alvarez

Posted on 3/29/22 by Brooke Burton

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Tania Alvarez, the current James Castle House Artist-In-Residence and a graduate of the New York Academy of Art masters program, was born in Sevilla, Spain where she lived for four years to connect with her paternal roots and find herself. Tania’s time there came to an abrupt end when she suddenly discovered, in her Citibank cubicle, the thing she’d been looking for: she called her English speaking boss and said, “I’m going home and I’m going to get an art studio. I need to be a painter.” Back in the United States, she hustled in New York City working nights as a bartender and days in the studio, which led her to graduate school. Since then she’s kept her head down, doing the work. So much so, in fact, that a call from Saatchi Art online almost went unanswered. (You can find Tania listed under the Saatchi Art Features tab, as one of about thirty 2021 Rising Stars.) Is there a trick to being discovered? Not exactly, but, mostly: find your own voice, take away restrictions on your creative process (in her case, an obsession with meaning) and be okay with making bad art. A lot of bad art. Because through trial and error, and with a lot of patience, you will find your art and that’s exciting.

Look at all this work! You’re moving right along.

Look at all this work! You’re moving right along.

That’s funny you say that, I’ve been so hard on myself, like, “You’re not making it fast enough.” [laughter]

Well, how many days have you been here?

Monday was three weeks.

And you’ve got one, two, three, four … twelve, thirteen fourteen, fifteen works in process. Not to mention two of them are elaborate, three‑dimensional sculptures.

Those took a long time. I think that’s why I started getting hard on myself, because these took me away from painting.

You think, “I came here to paint, I must paint!”

Yes, but I got very excited about materials, I’m really drawn to James Castle’s three‑dimensional assemblages. I was able to handle some of them.

You were allowed to touch the art? Lucky.

I was thinking, “Wait, are you serious?”

How was it?

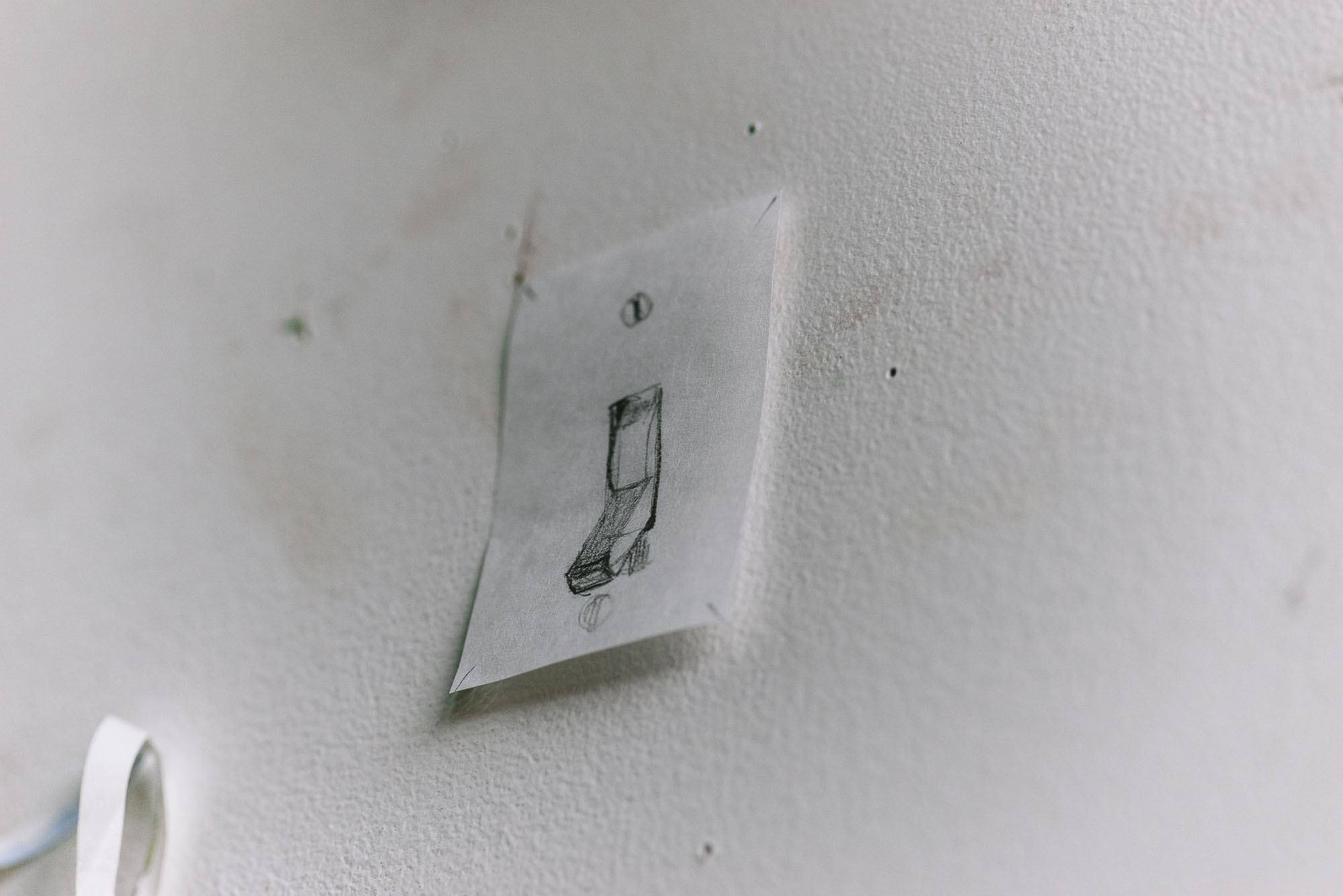

It was an emotional experience. I’ve never had that before in my life. There was something about feeling the artist’s hand in the material. Later that night, I was thinking about my house, the house my partner and I just purchased, about how much it means to me. I thought it would be interesting to rebuild it from memory using recycled materials. I didn’t know how. When I finished the first version, I was like, wait a second, that’s not my house, it doesn’t look like this. Because you know, when recalling something from memory, it shifts and changes. Then I made a blueprint and came up with the actual shape, for the second version.

So these are actually small sculptures representing stages of remembering.

Exactly. And the materials themselves. They will be displayed so you can see how they’re built.

Oh, that’s why you have the mirror, to see the inside.

The material is a memento of the time I spent here and what I was eating.

A memento of frozen pizza.

Amy’s pizza. [laughter]

So you got to hold Castle’s work at the James Castle Collection and Archive?

I’ve heard stories of friends saying “Oh, I was at the museum, and I saw this painting, and I burst into tears.” And I have never had that. I’d think, “Really?” At the archive, [Andrea Merrell] takes out a sculptural sewn piece, and puts it in my hands. It made me burst into tears. I looked up, “I feel like I’m going to cry. Oh, my God, I’m crying, what’s happening?” [laughter] It was sort of embarrassing and powerful at the same time.

I look at so many images of art on screens, sometimes I forget there’s an object. Museums and galleries don’t like you to touch the art.

Feeling the weight of the material and imagining [Castle] pushing the thread. You feel the hand of the artist in a way you don’t in a museum.

I’m a little jealous. So, you weren’t born in the States?

I was born in Sevilla, in Spain. My father is Spanish and my mother is Italian, from Sicily. They met in Switzerland and had my older sister Natasha, then moved back to Spain close to my father’s family. After they had me and my sister Veronica, my mom’s father became sick, so we came back to the U.S. My mother was naturalized when she was a child.

Do you have dual citizenship?

Yes. In first or second grade, we moved to Upstate New York to this place called Hoosick Falls; my parents had met another Italian family who was selling their restaurant. We ended up moving up there and taking the restaurant.

Is running a family restaurant a big deal?

Oh, it was huge. I remember falling asleep on flour bags in the back storage. That’s where I had all my meals; it’s where I’d go after school. I grew up in the restaurant business. Once I was old enough, I was washing dishes and cleaning and whatnot.

Eventually you attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. How was that transition?

Oh, God, I mean, coming from a small town, first to Utica, which is a semi‑big city, and then to this huge city, to Brooklyn—I had just experienced a huge loss—my father passed away right before I graduated their two‑year program in Utica before the second half of the program in Brooklyn.

That’s hard.

My time there was difficult in many ways. When I graduated, I moved straight to Europe. I just needed to find myself.

Bye New York!

I moved to Spain. I wanted to learn Spanish and get to know my father’s family, because they are all still there. My grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins, everyone. I also did a postgrad in Spanish, which was nuts. Graphic Design. And I did get to find myself and figure out what I wanted to do.

What did you figure out?

It was easy to find an English‑speaking job and I ended up working for Citibank. I worked there for four years; one day I was just sitting in the office, looking around—I had this little cubicle, and thought, “Wow, what am I doing?” I called my boss, “Hi, you know that vacation I’m taking for Christmas? I’m not coming back. I’m going home and I’m going to get an art studio. I need to be a painter.” He said “Wait, what?”

[laughing] How did he take the news?

He said “I support you. I’m a photographer and I gave it all up for stability.”

I wonder what pushed you over the edge that day?

I had this little wall of doodles; every time I’d be on a phone call, I’d be drawing. I was looking around and it was so stale, there was just no creativity and I was working in Excel. I thought “What happened to my life?”

Excel happened.

I’d had enough.

Did you have a culture shock coming back to the States?

Oh, yeah, I’d gotten to a point where I was dreaming in Spanish. I think my life has been about culture shock. There were always mixed messages growing up; at school I was trying to be American, then kids would come over and my parents were speaking a different language and they looked very different. I think my life has always been about finding a place that felt like home, or a place where I belonged. A lot of immigrant children feel that way, “Where am I from?” I didn’t feel like I was from Spain, I didn’t feel like I was from the U.S., coming home. Where do I fit in?

That’s an internal question.

I think that’s the name of the game when you’re not one-hundred-percent from somewhere.

Did you set up a studio right away when you came back?

I’ve gone through a lot of hard stuff, there were a lot of hurdles. But somehow, there’s been a little angel that keeps making things simpler for me. So, at the time, my sister was working at a nightclub, bartending in the city. She could work just three nights a week and pay her rent in New York City, I thought, “Wait a second, I was working five days a week and struggling in Spain.” We were out with her friends and I said, “I wish I could just bartend and spend the rest of my day in the art studio.” Her friend said, “Oh, I own a bar. I need a bartender. Do you want me to teach you? Do you want to start this week?” I thought he was hitting on me, because it’s really hard to get a bar job there, it’s completely unheard of in New York.

Really?

Oh, it’s good money.

Was he serious?

He was serious. From 2009 to 2017 I was bartending and painting. I worked my butt off. I was getting home at 8:00 o’clock in the morning some nights, so I was kind of a zombie, but I did it. It got me to the point where I was able to go for my master’s at the New York Academy of Art.

Yeah, you worked your butt off.

I was making abstract assemblage‑based works and the New York Academy of Art is very figurative; representational. They were a little confused at first, about why I wanted to apply. But I was determined—it’s funny, my work had been really derivative of some of the artists I admired: Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine; I loved them so much. But I wanted my own voice. I felt if I got trained in a more representational way, maybe it would happen.

You needed a fresh start?

I think it did what I wanted it to. I gained confidence. I knew I could [work representationally] before, but I’d let go of it so much that I lost confidence; questioning, “Am I phoning it in? Do I actually know how to paint?”

I think confidence in your skills is very important.

I just knew I wanted to get better. Painting was like my mode of therapy too. A way for me to process my life. I knew if I just kept pushing, something would happen. Also, I didn’t want to stay in the bar forever. Which, I mean, painting isn’t necessarily going to get you out of the bar, but—

Sometimes art gets me into the bar. [laughter]

But I knew if I just kept working at it, I could start showing, and people would want to live with my work.

Do you have advice for artists who feel stuck?

Be okay with making bad work. Make a ton of bad work.

Did you do that?

Oh, yeah, I made really bad work. Some are in dumpsters. [laughter] Also, take note of what you’re interested in. Find the ties in the work because there’s something there. I would journal. It will come eventually.

How do you know when it’s yours?

Through trial and error you find it naturally, you have to be patient. Then I think you just feel it. When you start making your work, people are going to connect with it. It’s also just stopping the obsession with what it means. I literally have stopped thinking about that. It puts so much restriction on the creative process. Now I let the work just come out, then, after I make it, I start to understand it.

How did you learn that lesson?

During grad school, I got very sick and it seemed like everyone put a lot of pressure on my process, “I wonder what’s going to happen to your work, are you going to paint about it, are you going to do this or are you going to do that?”

How far along in the program were you?

Everything seems to happen during my last year of school for some reason. Two months before I graduated I got really sick, and there was just a lot of talk about what would happen to the work and what I would paint. It’s just stifling. I wanted to process what happened to me, by myself, and not have the pressure of where the work’s going to go. I don’t want my whole life to be about that, there’s more to my personality, to me.

Is that freeing?

Yes and I feel more connected to the work I’m making. Even when I look at it, I’m more proud.

That’s exciting! What a great place to be.

I’m definitely excited. Looking at these little houses, I’m just so excited.

Tell me about your interiors.

The work I was making before, I called them imagined landscapes, or, dreamscapes. Some of them I thought of as responses to trauma, physically being in one place but emotionally or mentally you’re elsewhere.

Disassociation?

I was thinking a lot about that before. Now, I’m working a lot with my own house; it’s reconstruction, history.

Congratulations, you’re a homeowner!

Yes. It’s just constant renovation. The house was built in 1850 so it’s got a lot of problems. We’re constantly finding new disasters to fix. I’m thinking about being back there, in my emotional headspace, but being here as well. Here and there.

Simultaneously.

I think of it as like mementoes of a time and a place.

Nostalgia? You miss your house.

I miss it. That whole process of building a space that’s yours.

A place where you belong. Or, some of these paintings are so small, like miniature interiors, it’s almost like they belong in you.

Yeah, for sure.

Why do you think you’re drawn to interiors versus figures or landscape or still life or—?

I’m puzzled by that sometimes, too. There are so many stories to be told through the spaces we live in, they’re so personal. Whether it’s the corner of a room or the pattern on the floor, there’s history.

And layers?

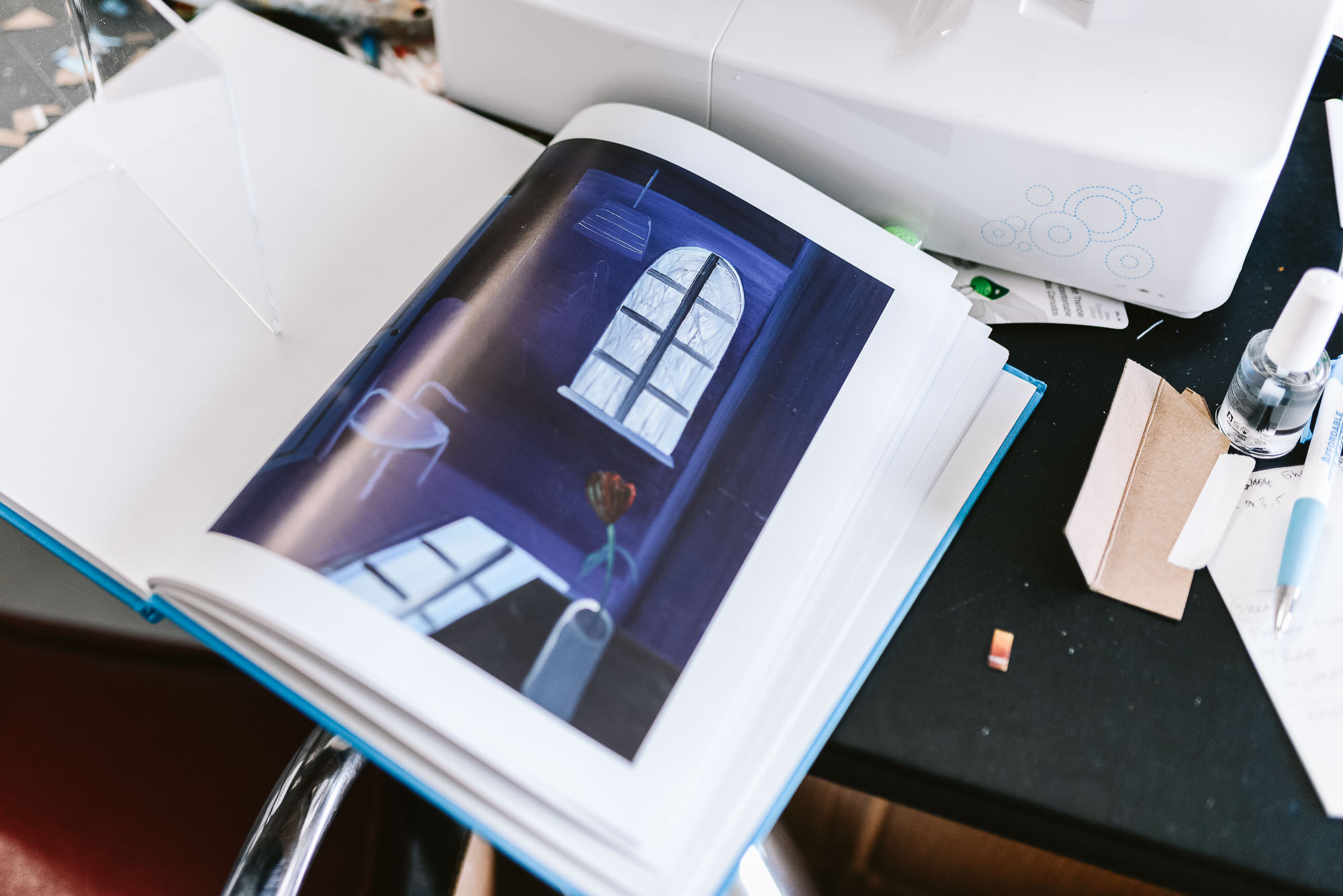

So many layers. A person doesn’t have to be in it in order to tell the story. I think that’s what’s so magical about it. The view through a window, like, looking at this Matthew Wong book, you feel the kind of person he was, to see the beauty in one flower. There’s so much poetry to it. We live in such a noisy, chaotic world. I want my images to be kind of quiet and contemplative. I was thinking of one of like a breath, you know?

An exhale or an inhale?

Maybe an inhale. I think the inhale is the more pleasurable part.

I’m kind of partial to the exhale.

I hold my breath a lot when I paint. So to take air in feels so good.

Going back to other people connecting emotionally to your work, does that translate to shows and sales?

Yes. It just happened—there was a second where, I would post them on Instagram, these small pieces—it’s not even dry yet—

Some paintings sold before they were even dry?

They were selling really quickly. And then Saatchi online contacted me. They wanted to put me on some Rising Star’s list.

What did you tell them?

I was like, “Uh, yeah, sure.” But also, “What is going on?”

Saatchi Art is an online platform that is democratic; anyone can show and sell their artwork through the site. Charles Saatchi, the founder, is an art collector infamous for buying unknown, emerging artist’s work, causing other collectors to follow suit. That artist’s work sometimes explodes in popularity.

I’ve been on their platform since I came back to the States. My work’s been on there forever and I didn’t sell a thing. I thought I was wasting my time. Then they contacted me and asked me to update my profile, and said I’d been selected for “Blah, blah, blah.” I’m like, “Okay.”

They have curators who will feature groups of artists from the site, like an online exhibit. And they selected you for their 2021 Rising Stars feature?

I didn’t think it was anything. I almost said no to the interview. The woman on the phone says, “I think I should preface this by saying this is very competitive and you were selected out of thousands of people.” I was like, “Oh, really?” [Laughter]

She could tell you had no idea.

I didn’t know what was going on.

You were clueless.

She said “Only five people are doing these interviews,” so I was “Oh, I’m sorry, thank you.” I was so embarrassed.

This is hilarious. You did the interview, then?

I did the interview, they posted the whole thing, along with my work. I sold one or two things on Saatchi Art. Then it was gradual—one gallery contacted me for a group show. Then another one. Then PBS contacted me before I left for Boise.

That’s awesome! What’s it for?

Umm.

[Laughing]

I can look it up. I’m really bad at this stuff.

What an honor. It’s funny you were selected for something you did not apply for, and for which you did not know the significance.

Thank you. [laughter]

Is there a trick to being discovered?

You just have to make the work. Put your head down and stop paying attention to everyone else, because when the work is right and when the time is right, it will happen.

I just have a couple more questions, they are fun ones. What are your best qualities?

Like as a person or an artist?

…

I think I’m very sensitive, which people can think of as a weakness, but I think that it’s been a strength. I’m very persistent and driven. I guess those are good.

Last question, did growing up in the restaurant business make you a food snob?

Oh, it’s terrible. I am a very big food snob. I kind of hate that. Like, it’s hard going to people’s houses, sometimes.

Because?

I don’t know, the food’s not done, not to the way, like, I know it could be. [Laughter]

What do you like to eat?

I’m pescatarian, I eat fish. I really like chargrilled salmon.

Mmmm, chargrilled anything.

So good. Grilled vegetables, or a really good wood‑fired pizza.

I love wood‑fired pizza too.

Olives, cheese, anything salty.

I think we’re hungry.

Collister, Boise, ID

March 30, 2022

James Castle House Artist-In-Residence

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.