Creators, Makers, & Doers: Gracieux Baraka

Posted on 7/14/22 by Brooke Burton

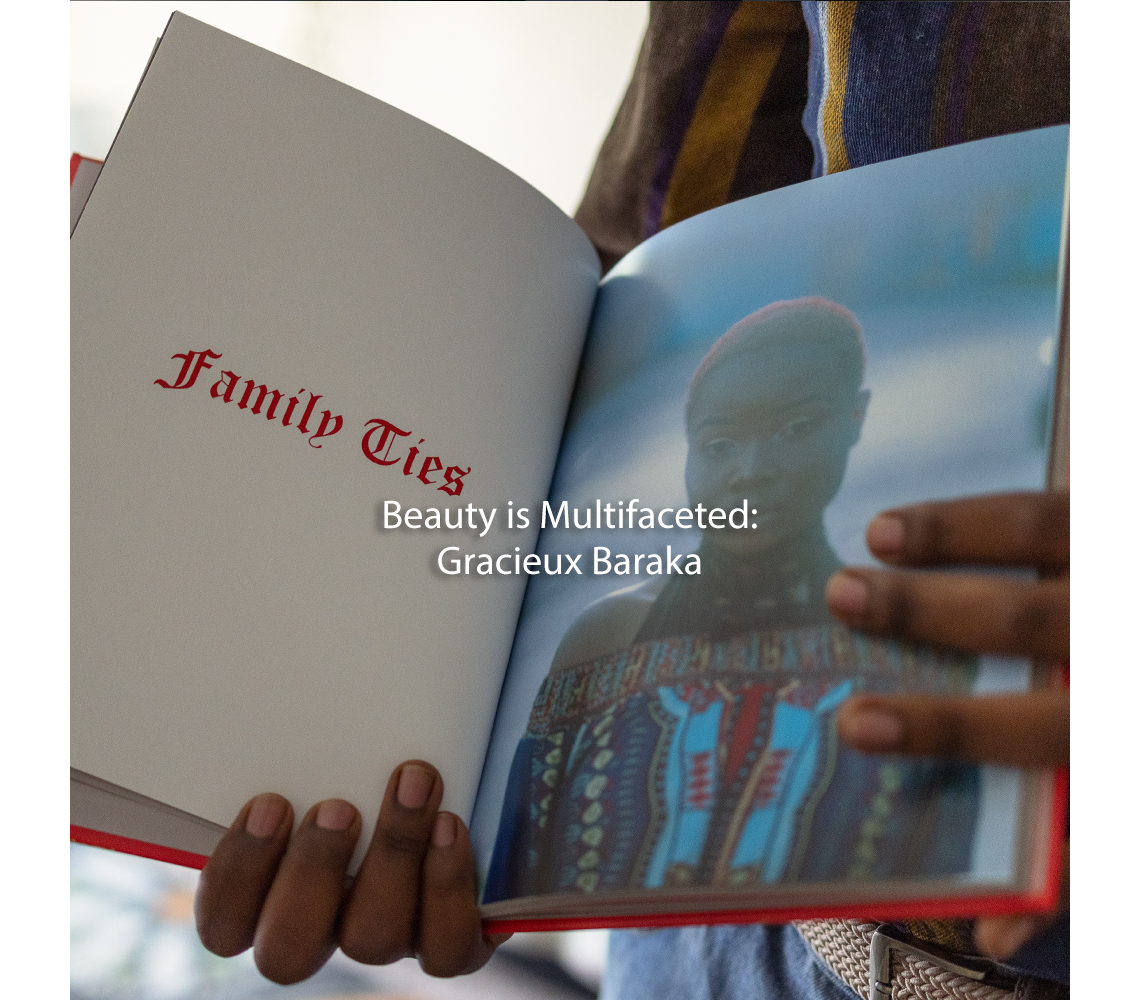

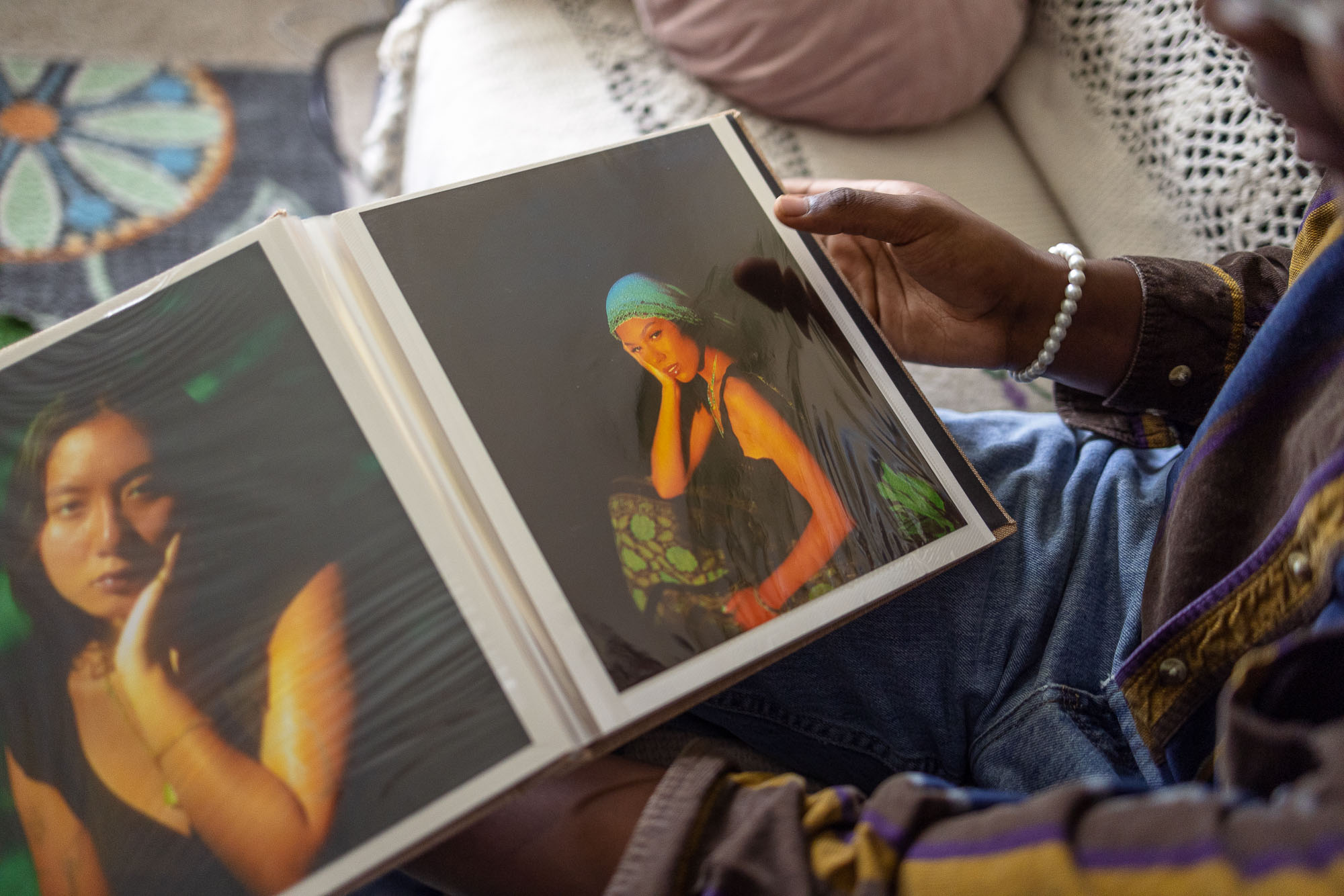

Interview & Photography by Brooke Burton © Boise City Department of Arts & History

Gracieux Baraka is a visual artist using photography and video whose work is included in the City of Boise’s COVID Community Collection. We shared a quiet afternoon co-creating his portrait (see below) and talking about the gradual shift in his work that mirrors his own personal transformation. What changed? Gracieux describes a time of newly found BIPOC friends and collaborators (your new best friend could be right next door,) and a circle of acceptance and love that permanently changed his perspective on the creative process. He describes his approach to accepting loss and grief, and overcoming an internalized Eurocentric scale of beauty. At the end of the day, what does he need for storytelling? Self love, human connection, and nourishment. And food. Always food.

How would you describe your aesthetic?

How would you describe your aesthetic?

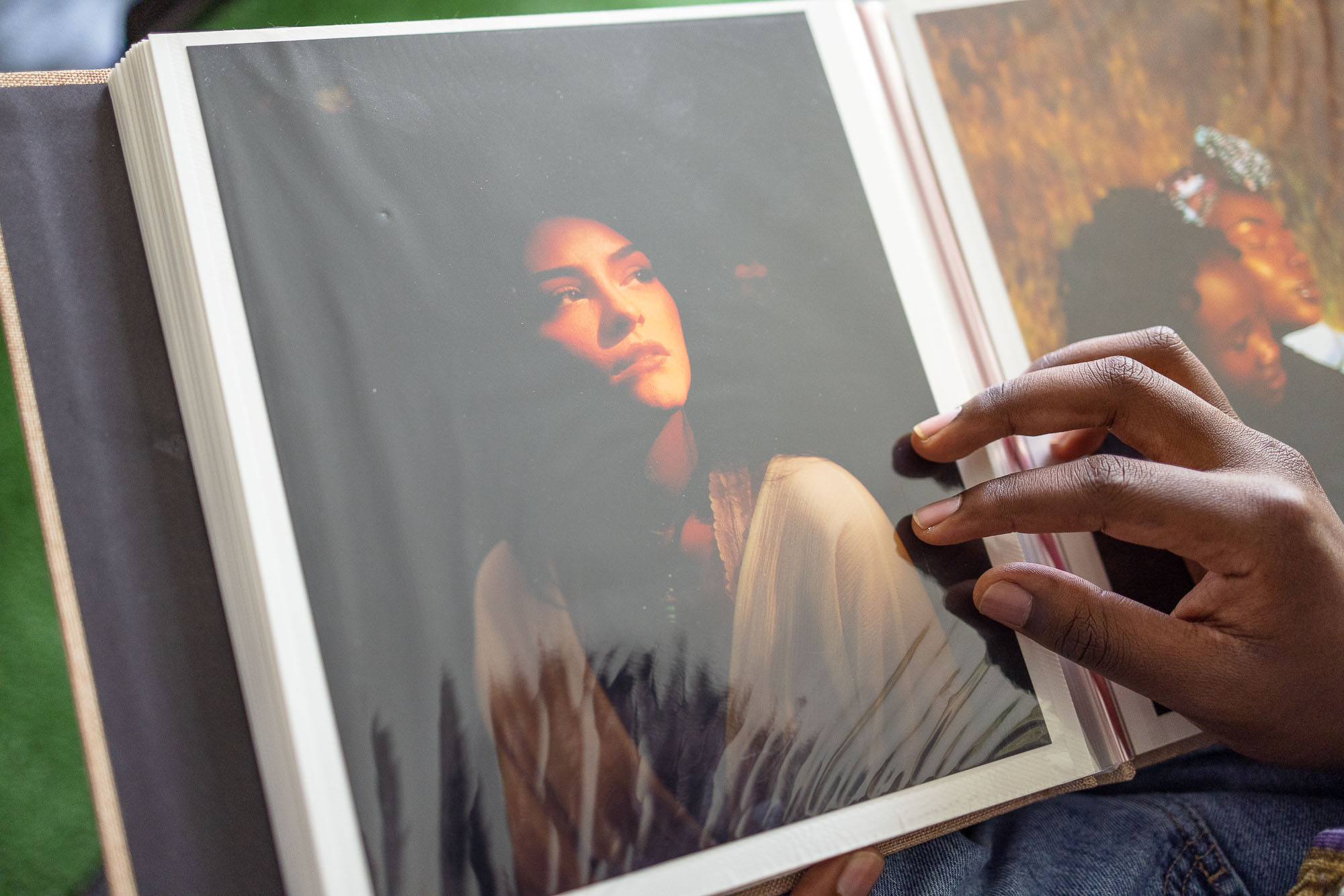

I started out doing what everyone was doing, this teal and orange clarified look I saw on Instagram, I started doing photography as a sophomore in high school. Later, I decided to edit a little differently and got a cleaner, softer look; I remember thinking, “Oh, this is what I was looking for.” I stuck with that for a while. In 2019, my look transformed into an homage to painters from my college art history classes. I remember working with my friend, Carnissa, who’s also an incredibly talented artist. We took photos by the bridge in Twin Falls; she wore a scarf that reminded me of the women who came to see the tomb of Jesus.

New Testament, Mary Magdalene—in Biblical illustrations, they wore head coverings. Who are some of the painters?

I love Pierre-Auguste Renoir. I love Caravaggio. I’ve been really into Edward Hopper. I love Wyeth. I love Georges Seurat and Monet and Van Gogh. I remember thinking, “How do I make this picture look like a painting?” I would shoot photos with little pockets of light coming through the leaves of trees so it would look like a spotlight.

Chiaroscuro.

I tried to see how far I could take it. I would directly reference specific paintings.

With posture? Composition?

Yes. The Grande Odalisque is one.

You wanted to re-create it?

I did with my friend Ale, it was magical; I really did what I set out to do.

That’s a good feeling. You’re also writing. Which authors are you drawn to?

Lately, James Baldwin. His history is a bit like mine. I grew up in the Catholic Church and I think he grew up in a denominational faith. A lot of his story feels as if I were reading about my cousin’s life, if that makes sense. Nikki Giovanni is one of the most talented poets; I’ve listened to her album “Like a Ripple on a Pond” constantly. It’s instrumental and poetic. In my work, honestly, I’m trying to say thank you to the artists who have shaped me. When I listen to a song that moves me, I can’t help but think, “How can I find ways to appreciate this song with my creativity, with my actions?”

To express gratitude?

The heart of a lot of my films is gratitude.

What can someone expect to see and hear when they watch your films?

I would say—they all have food. [Laughter] Food is always this little character who’s mischievously making everything happen. Color. I love color.

Very saturated color.

Poetry or a poetic nature.

There’s often a narrator.

I’ve been the narrator in a couple of my films, but I’m transitioning to other narrators. I think it makes my work more complex because when someone voices your words, it adds a layer.

Your collaborator brings their whole personal history and point of view to your project. I know some of your story; how did you come to live in Idaho?

Through a resettlement program that my family was part of. There were years between knowing the prospect of coming to America and actually coming here. It was kind of an agonizing hope for me. To wait so long knowing it was a possibility made life a little harder and sometimes a bit sweeter.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Congo. My family moved to Kenya, where I grew up for about 11 years. I didn’t feel attached to anything there, it felt like a transitional space. Even on days it did feel like home, it didn’t feel like my forever home.

Does this feel like your forever home?

I don’t think so. I have dreams of living somewhere else completely. I want to live in Japan for a while. I’d love to live in Europe. I feel like there’s different sensibilities with different cultures, some that American culture lacks, generally, and that other cultures have an abundance. At the end of the day, I might feel like, “Oh, I think Japan is my home or I think, you know, France is my home. I’m as open‑ended to that prospect as I was when I lived in Kenya about America.

How old were you when your family left Congo?

I believe I was four. I think the civil war was definitely a catalyst, but I remember my dad moved to Kenya before my siblings and my mom. My parents worked in my school, they made the uniforms. My dad had an atelier in the school compound. I think I was around 15 when we came here. It was one of those feelings I might never experience in my life again. The amount of newness that happened between the flight from Kenya to our arrival here. I remember America had this smell. It’s funny, it’s like, I don’t know if I could explain it, it’s like fried egg. Honestly, like that’s the only way I could have explained it.

I know what you mean; your flight lands, you step outside for the first time and notice differences in the atmosphere: climate, air quality, humidity, scent. About cultures having a sensibility, what are you observing?

I’ve been into cultures that have a sense of community. Not the kind of community I experienced in Kenya; the eyes‑on‑you surveillance, your mom’s friend, like, while you’re out with your friends, is-

Tattling?

Yes. I remember not liking that. But I’ve been fascinated by cultures that have a warmer, softer sense of community. Say, you’re having trouble and you have a daughter, your neighbor says, “I’ll take care of her while you sort it out” this and that. Or “You don’t need to worry about groceries this week, I got you.” The movies I saw about America were—every time someone moved into a neighborhood, the neighbors would bring fruits and fish—

Casseroles.

That idealized sense of community, that is in America, but isn’t present everywhere.

But it is well represented in popular culture and entertainment.

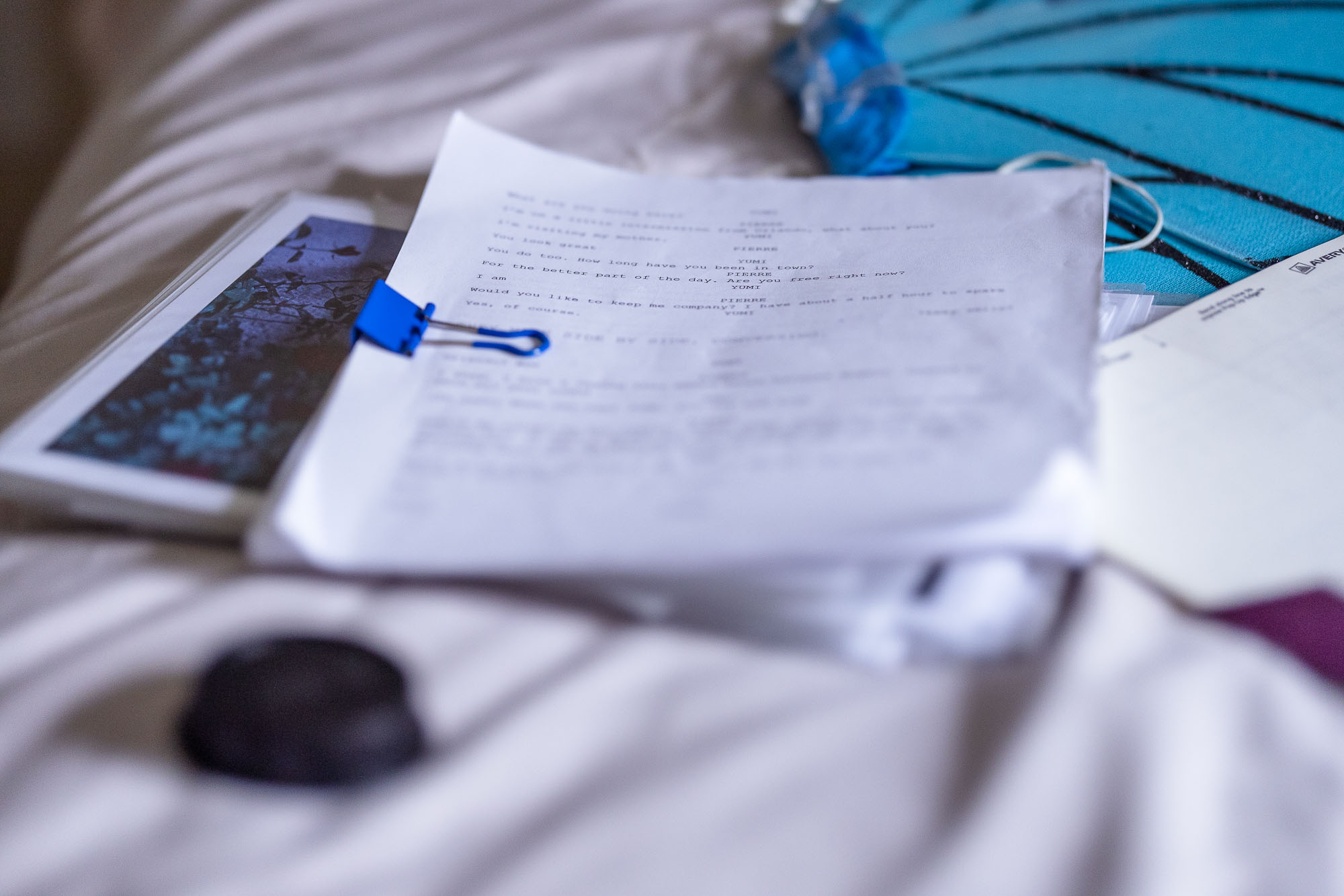

The Norman Rockwell picture of America, the newspaper boy, a milkman bringing you milk every morning, and anytime you move to a new neighborhood, there’s a casserole waiting for you. I’ve been trying to cultivate that in a way that feels natural in my life, especially when it comes to fellow artists, that’s where my community starts. Especially in my work, I want to use my art as an opportunity to reach out and to ask for help but also to get to know who’s around. You’d be surprised; you could be living next-door to your best friend and not know it. I worked on this film, and thought “I don’t think anyone will get this.” I reached out to a friend of mine on Twitter, because her username told me “I think she will get it” and I said “Here’s a script I wrote, tell me what you think.” She loved it. We worked on it for a couple of months and made a beautiful short film. It’s honestly one of my favorite works.

What is the name of your film?

À la recherche du temps perdu. It’s inspired by Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. My film’s title translates to In Search of Lost Time, or Remembrance of Things Past, depending. I thought it would be cool to reference Proust and things I learned in high school about philosophy and literature, Schopenhauer and Kafka. I wanted to make something that could transcend the expectations people would have of me, a young, Black artist in Boise. I wanted to make something that would shock me.

Why Proust?

I latched onto this moment in [Proust’s] book, the character is having a madeleine when he remembers his grandmother, he remembers living in the countryside, he remembers his childhood best friend. What I had to do was find the steps back, the steps towards that moment. I wrote about grief and coming to appreciate things you may have lost, instead of tearing them away from the fabric of your history.

Tearing them away because the loss is painful?

Sometimes it feels like the only way to move forward or not be tied.

A way to fix the uncomfortable?

Working on that film was really good for me because it really brought in my love for humanity through collaboration.

Wonderful. Do you specifically seek out models who are BIPOC?

Finding beauty in myself made me transition to working with people of color and Black people. My whole photography career, I’ve always wanted to do that but the problem has always been proximity. My high school population was primarily white people. It’s funny how everything sort of works out perfectly. I had to work with who I was around. In college, I was around more Black people and people of color and I began to see my own beauty as a Black person; it happened as an organic expression of where I see beauty and who I work with.

A convergence of sorts.

The way I use light changed as well. I realized gold is a beautiful color; I had a [photography] reflector and used the gold side, which isn’t as pleasant with lighter skin. But with Black people, it is very beautiful. Like I said, the people I work with tend to move me a certain direction. Part of the reason I love my work right now is because of the opportunities I’ve had working with Black people and people of color.

You said it came at a time when you were able to see yourself as beautiful?

It’s a complex issue; even when I was living in Kenya around Black people, I didn’t feel like the most beautiful person in the room. The sort of Eurocentric scale of beauty exists everywhere, even in Black spaces. The outside view people had of me affected the way I viewed myself. When I came here, even in conversations with lighter‑skinned people in my class, my circle, whatever, they were seen as the beautiful people. I internalized that, being second to someone, always. That made me blind to my own beauty. It took me a while to really like my nose, because my nose wasn’t pointy. It’s more wide. [Chuckling] Like my skin—yeah, my skin. The way my hair is, it’s all of these, from the big things to the little things. I always felt like second place. It took me a while to be first place in my eyes. It took a while to look at myself and love everything about myself. That really had to do with being around other Black people who showed me how special it is to have the nose I have and to—I think the more love I was surrounded with, the more love I had for myself.

Oh, you make me cry.

Getting used to that love took a while, but it shaped the way I see myself and in turn, the way I approach how I see other Black people and how I see beauty, in my family, my community, other communities. Now I look for it everywhere. I’m fascinated by how different people, even in Africa, have such distinct styles and ways of talking and ways of looking. Beauty is multifaceted.

What do you need for storytelling?

To be able to tell your story authentically, you have to see your own beauty. That’s my favorite thing about being an artist; you have to be on your side when telling your story. The journey finding beauty in myself, finding beauty in Black people, finding beauty in Black art—it’s all helped me tell my stories in a more authentic way. When it comes to art, there are practical steps, but at the end of the day, we’re all living, breathing human beings. It’s not just a better camera, a better lens, better writing skills; you need real human nourishment. Whatever nurtures us as human beings will nurture us as artists. When we’re surrounded by love and when we see our own beauty, we will be better artists.

Bench Neighborhood

July 14, 2022

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Creators, Makers, & Doers highlights the lives and work of Boise artists and creative individuals. Selected profiles focus on individuals whose work has been supported by the Boise City Dept. of Arts & History. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individuals interviewed and do not necessarily reflect those of the City of Boise.